How the pursuit of eternal life shaped politics, culture, and fate in ancient China

Walk through the center of Beijing today, and the words gracing the gate walls at Tiananmen Square can’t be missed, “Long Live the People’s Republic of China, Long Live the Great Unity of the World’s People.” But far from just a political slogan, “long live,” or “wansui (万岁),” is a greeting that in Chinese history was used by courtiers to greet the emperor. Literally meaning 10,000 years, its use dates back to the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), when “long live” became one of the manifestations of the emperors’ supremacy, the exclusive right to a long life, and, in some of their dreams, an immortal one.

Throughout history, Chinese emperors have not only received wishes for long lives but have employed court alchemists to concoct immortality potions—the famed elixir of life, also known in Chinese as xiandan (仙丹), which has continuously fascinated humanity. First showing up in the history books 2,000 years ago, when scholars working in the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE) began attempting the alchemical prolonging of life, the pursuit of this xiandan has left a legacy of poisoning, persecution, and palace scandal. This was perhaps most evident during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), a cornerstone of Chinese civilization, when culture and trade flourished, bringing with them new ideas and influences.

In 805, at the age of 27, Emperor Xianzong, the 12th ruler, sat atop the imperial throne in Chang’an (present Xi’an city in Shaanxi province), the capital of the Tang dynasty. In the years that followed, Xianzong managed the resuscitation of the empire with straight-headed diplomatic skills, and for most of his life, this corresponded with a disdain for the mystical idea of immortality. In 810, Xianzong had taken the council of his official Li Fan (李藩), who warned him of the perilous history of seeking xiandan, quoting the Han dynasty poem “Driving to the East Gate (《 驱车上东门 》)”: “Seeking medicine for a god, mistakes are often made. Better to drink good wine and wear fine silk (服食求神仙,多为药所误。不如饮美酒,被服纨与素).”

According to the Old Book of Tang (《旧唐书》), compiled in the 10th century as one of the official dynastic histories, the emperor at that point “felt deeply” that this idea was correct. However, with the warfare and political rivals now settled, the emperor started to entertain more esoteric pursuits. Buddhism had existed in China for hundreds of years but flourished during the Tang dynasty. As the official dynastic history records, Xianzong began in 818 to employ a court alchemist, Liu Mi (柳泌), to cook up a Buddhist prescription of eternal life. His advisors were alarmed, suggesting that the emperor make the alchemist eat his own concoction for a year and observe the effects before imbibing himself, but to no avail. Xianzong even named Liu the governor of Taizhou prefecture, unthinkable for a lowly alchemist, so that he could have easy access to Mount Tiantai, where he claimed his pharmacopeia of xiandan ingredients grew.

In the spring of 819, Xianzong sought to popularize Buddhism by taking a relic—a bone of the Buddha—from Famen Temple in what is now Baoji, Shaanxi province, and displayed it in the imperial palace for three days. According to the official record, “Nobles, officials, and commoners hurried to donate at the Buddhist temples like time was running out.”

Read more about politics in ancient China:

- Ancient Snitches: How China’s Emperors Encouraged Informants

- How Prophecies Were Key to Maintaining Power in Ancient China

- Anyone seen the Son of Heaven?

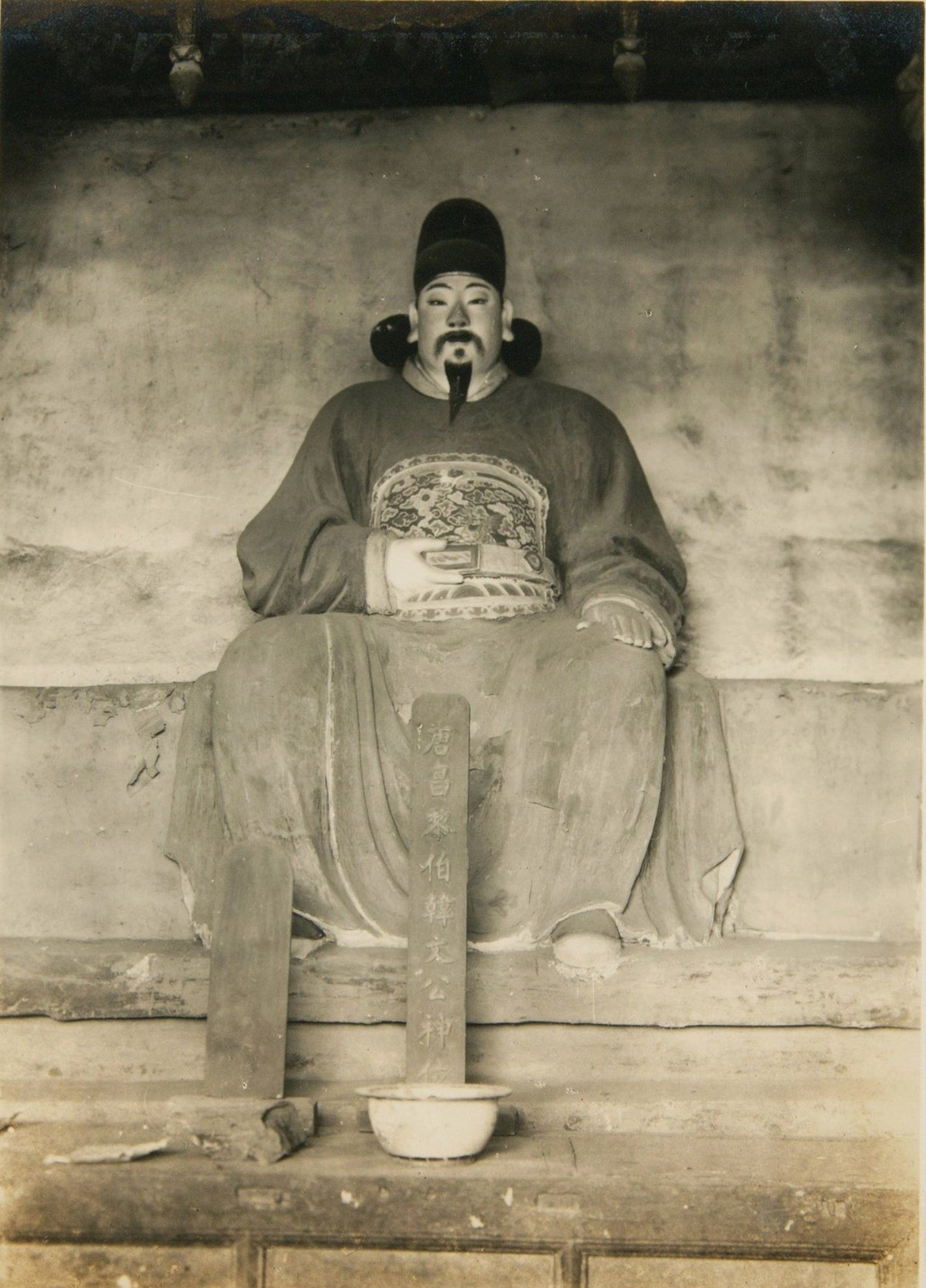

One man who was particularly dismayed at the emperor’s new proclivities was Han Yu (韩愈), a prominent writer, Confucian scholar, and official. He wrote a lengthy article addressed directly to the emperor himself, titled “A Memorial on the Relic of the Buddha (《论佛骨表》),” criticizing Buddhism’s history in China for bringing calamity to dynasties, early death to emperors, and disorder to the Chinese way. Han’s article enraged the emperor, who initially wanted to execute him but was persuaded to instead demote him to a position over a thousand miles away in Chaozhou, in what is now Guangdong province. “I deeply know Han cares about me,” Xuanzong told one of his court officials, according to the Old Book of Tang, “but as my official, Han is being too indiscreet in saying the belief in Buddhism will shorten the emperor’s life. I am just upset about his bluntness and nothing else.”

Unable to be convinced by his court associates, Xianzong continued to drink the potions prescribed by his alchemist Liu. His reign quickly descended into misrule and sickness, as the emperor began to miss council sessions, political factions emerged in the capital, and palace maids and eunuchs were executed for trivial reasons. Within a year, Emperor Xuanzong died, primarily due to strangulation by a eunuch who feared his own life was in danger, with a secondary cause being poisoning—not only of the body from the alchemist’s brew but also of the mind, seduced by the dream of immortality. His son and successor, Emperor Muzong, had Liu beaten to death within a month of taking the throne.

By the time Xianzong’s grandson took the throne as Emperor Wuzong in 840, Buddhism in China had continued to gain strength, strong in both followers and wealth amassed in temples. But Wuzong, an ardent Daoist, would undo all that.

Within the first year of his rule, he summoned to the palace a notorious Daoist monk and alchemist, Zhao Guizhen (赵归真). Zhao soon got the ear of the Wuzong, who was only 26 years old then. According to the official history, Wenzong devoted himself to Zhao as a teacher, and Zhao insistently berated Buddhism as a foreign religion that needed to be controlled.

Wenzong implemented Zhao’s ideas by first decreeing regulations on who could teach Buddhism and claiming temple wealth through taxation. He then ordered the complete destruction of Buddhist monasteries, temples, and shrines, as well as the seizure of all their wealth and property.

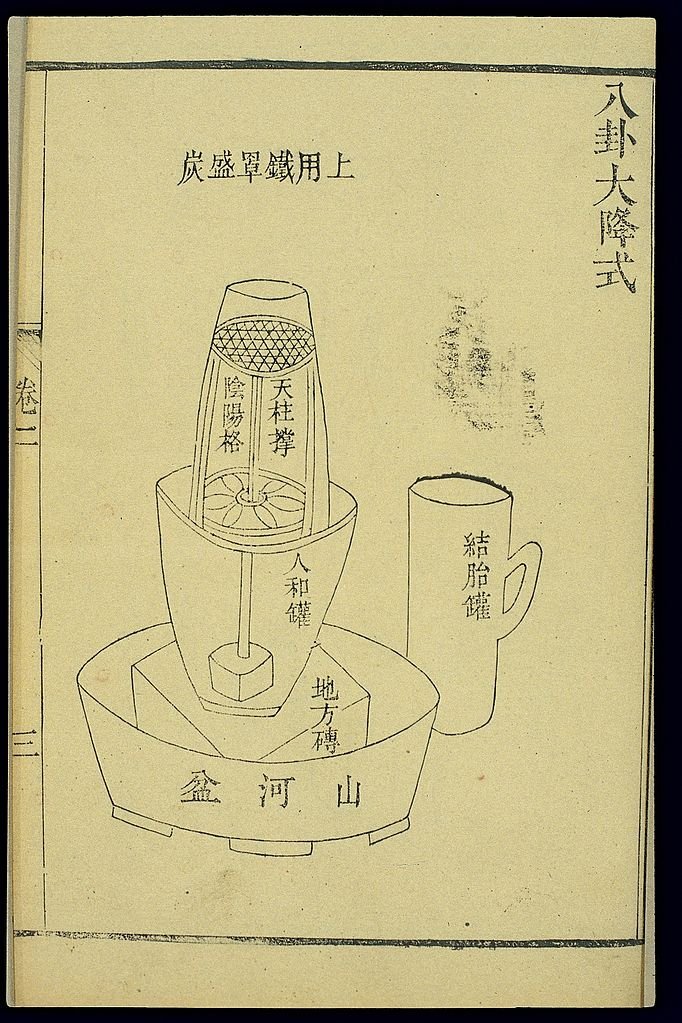

However, despite the change in religion, the pursuit of immortality remained. Daoism ascribed the pursuit of eternal life as one of the core tenets of the doctrine, and immortality could be achieved in two ways: one through prompting internal change through practices like qigong, known as neidan (内丹), and two through the consumption of external substances, known as waidan (外丹), or in common parlance, an elixir of life.

Driven by a desire for more power, the Daoist priest took advantage of Wuzong’s obsession with the elixir of life and deceived him. Zhao made up elixir ingredients that were impossible to obtain to complete his mission: 5 kilograms of plum cover, 5 kilograms of peach fluff, 5 kilograms of raw chicken membrane, 5 kilograms of tortoise fur, and 5 kilograms of rabbit antler, as recorded by the Japanese monk Ennin in his famous work, Ennin’s Diary: The Record of a Pilgrimage to China in Search of the Law (《入唐求法巡礼行记》). Eroded by poisonous elixirs, Wuzong’s illness deteriorated, and he became more emaciated and irritated day by day. According to Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance (《资治通鉴》), a chronicle compiled in the 11th century, Zhao recommended Wuzong to take one golden elixir which was made of sulfur. While Wuzong suspected Zhao’s elixir was the cause of his illness, Zhao argued that the main issue was Wuzong’s real name Li Chan (李瀍), having the water element as its radical, incompatible with soil worshiped by the nation. “You should change to a name with more fire elements, harmonious with soil.” The credulous emperor thus changed his name from 瀍 (chán) to 炎 (yán), composed of two fire characters. However, the change of name could not save Wuzong from his poison, and 12 days later, he passed away at the age of 33.

Such a pursuit for immortality potions continued throughout Chinese history, from the 16th-century Ming Emperor Jiajing, who drank menstrual blood, to the Qing Emperor Yongzheng, who allegedly died of elixir poisoning as late as 1735. Today, narcotics remain widely popular worldwide, despite their known dangers, as do aesthetic surgical procedures aimed at preserving youthfulness. How far away is this history from news of the present, such as the tech billionaire Peter Thiel, who is “on a mission to cheat death,” as the British newspaper The Telegraph put it, and plans to have his body cryogenically frozen?

Despite its deadly consequences when pushed to the limits of reality, alchemy as a science also produced many chemical and medical breakthroughs, byproducts of the dream of immortality. It is perhaps not a coincidence that while the Tang rulers were eating their own death, inventions such as printing technology and gunpowder came to be. Just as the character for the dan (丹) of xiandan represents a crucible with a piece of the mystical mineral cinnabar inside of it, the Tang world served as a crucible of exchange for culture, science, and at times, impossible dreams.