Learn these essential Chinese “chengyu” to call out treacherous and deceitful people

On July 21, a Ph.D. student at the prestigious Renmin University of China took to the microblogging platform Weibo to share allegations of having been sexually harassed and assaulted by her supervisor Wang Guiyuan over a two-year period.

In the since-deleted, nearly hour-long video, the female student is seen holding her national ID card in front of the camera before sharing details of how Wang had verbally and physically abused her, including threatening to prevent her from graduating in 2022. She also plays an audio recording allegedly capturing the moment he repeatedly tries to kiss her.

The allegations were particularly explosive given Wang’s position—associate dean and Party head of the university’s School of Liberal Arts. Shortly after the allegations came to light, the university published an announcement that they had confirmed the authenticity of the incident and that Wang had been stripped of his titles. The police has also launched an investigation into his behavior.

The incident sparked heated discussion on Chinese social media, and the video was viewed at least over 15 million times before the post was deleted on Weibo. A related hashtag has accumulated over 60 million views at the time of writing.

The discussion mainly focused on the moral standards of educators. Because campus life has always been portrayed as a pure, unworldly environment in Chinese society, educators are often highly regarded and respected almost unquestioningly. However, numerous revelations over the past few years about impropriety among professors show that some educators have abused their power to mask illegal conduct that harms students.

In light of Wang’s hypocritical behavior, let’s take a look at some expressions used by netizens to condemn such duplicity in Chinese:

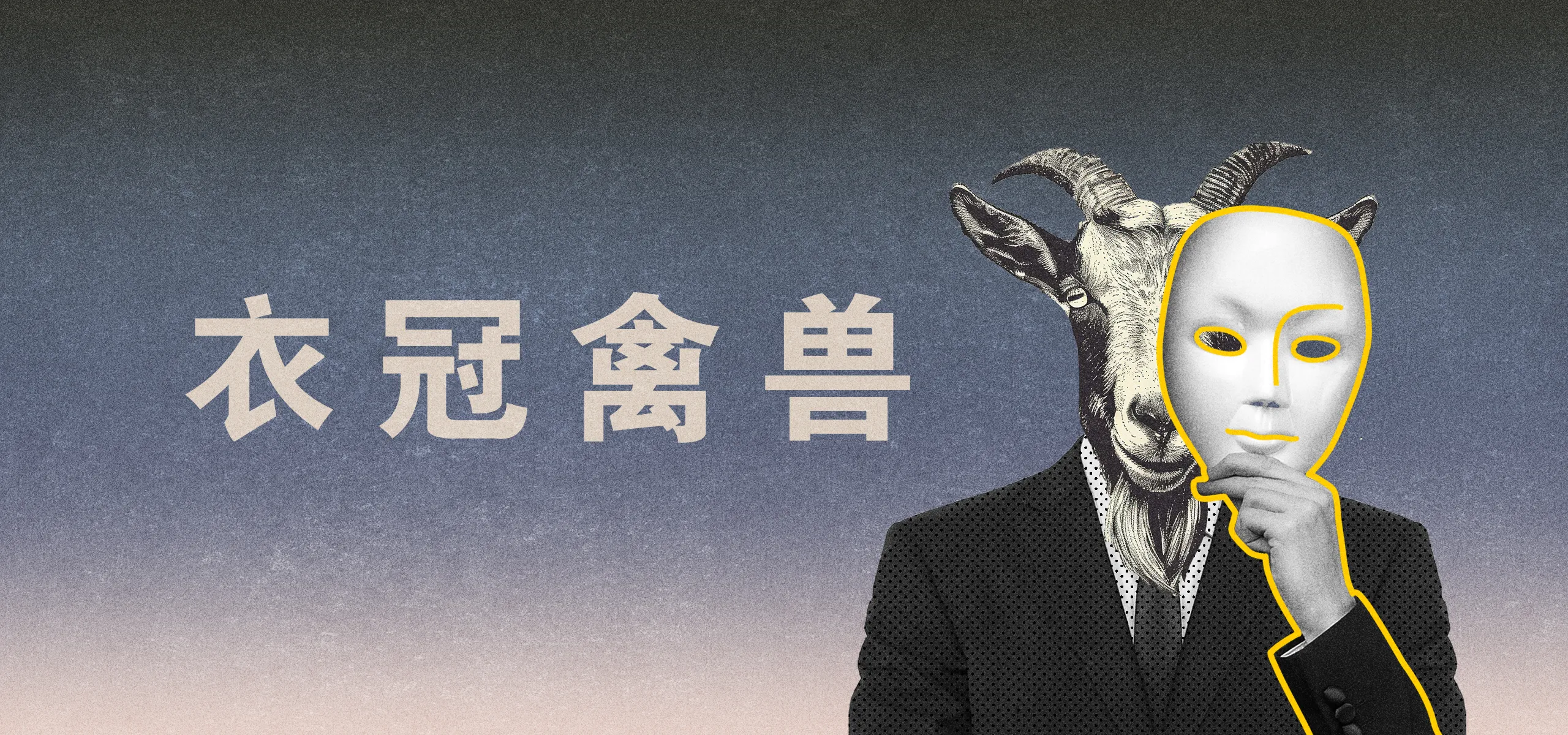

Beast in human attire 衣冠禽兽

Netizens were swift and unanimous in their depiction of Wang, dubbing him “A beast in human attire.” This chengyu refers to someone in a high position who may appear decent in public—particularly in dress—but, in stark contrast to the person’s appearance, acts immorally out of the sight of prying eyes. In Wang’s case, we can say:

The teacher appears to be a decent man, but he was recently reported to have sexually assaulted his student. He’s just a beast in human attire.

这名老师看起来仪表堂堂,但是他最近被曝光性骚扰自己的学生,简直是衣冠禽兽。

The expression, which directly translates to “clothes, hats, birds, and beasts,” once had a positive meaning. It specifically referred to royal court officials in ancient times, who had high social status and largely received respect and admiration from citizens. According to Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty (《大明会典》), a legal code compiled during the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644), court officials were required to have animals embroidered on their uniforms according to their type and rank; civil officials’ sported birds to represent their civility, while military officials had beasts to show their might.

During the middle and late Ming dynasty, royal court officials were considered to have become increasingly corrupt and neglectful due to a lack of supervision, low wages for lower-ranking officials, and the attractiveness of extravagant lifestyles. As a result, the meaning of this chengyu has also become derogatory, describing those who seem upright and of noble status but are actually depraved and untrustworthy.

A similar chengyu is 人面兽心 (rénmiàn shòuxīn), which literally means someone with a human face but the heart of a monster.

Gold on the outside, but rotten on the inside 金玉其外,败絮其中

In the political allegory Discourse with a Mandarin Vendor (《卖柑者言》), written by the late Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368) military strategist Liu Ji (刘基), a man is described as having been sold what appeared to be a plump, golden, shiny mandarin orange. However, upon peeling the fruit, he discovers that the insides are dry and coarse like a worn-out cloth. When pressed about cheating customers with inferior goods, the vendor, in a particularly honest turn, compares his mandarins to the royal court officials of the time: They may look decent and respectful with their high social status, but are negligent in performing their duties. In other words, they have a glorious appearance like gold and jade, but really they’re messy, impractical, and worthless—just like the mandarins he is selling.

“Instead of complaining about them (the royal court officials), you come after my mandarins,” the vendor exclaims. Exasperated, the author falls deep into thought. He comes to the conclusion that the vendor’s fruit is just a vehicle for him to express his grievances with the failings of society.

In modern days, the idiom is used to caution people from being deceived by appearance. For example:

Be careful when you go on a blind date. Some people may appear charming but are actually “gold on the outside, rotten on the inside.”

约会时一定要小心,有些人看起来风度翩翩,其实是“金玉其外,败絮其中”。

Two-faced 两面三刀

The chengyu translates directly to “two sides and three knives.” Before becoming a commonly used idiom, the phrase was slang used in the construction industry to praise a bricklayer for his immaculate skills: Before work, a good bricklayer would check if the adhesive on two sides of bricks, usually the top and bottom, are were smooth and flat. While laying a brick, the mud on the tile knife should be applied equally to the bricks three times. Otherwise, the wall would look crooked.

But now, the phrase is commonly used to describe a person with deceitful and insidious qualities who gets ahead at the detriment of others. Its first documented use with this negative connotation can be found in the Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368) verse play, or zaju (杂剧), “The Chalk Circle (《灰阑记》)” by Li Xingdao (李行道). In the play, Li tells of a crime solved by Bao Zheng (包拯), a politician during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279) known for his honest and upright handling of legal cases, and later considered the paragon of fair arbitration in China.

In the story, Zhang Haitang, a beautiful young woman and former prostitute, marries the wealthy Ma Junqing, becoming his second wife and later giving birth to his son. Ma’s first wife, scared that Ma would find out she’s also having an affair and hoping to have his fortune all to herself, poisons him and tries to frame Zhang for the crime. She also claims Zhang’s son as her own in order to inherit Ma’s fortune.

In the court, Ma’s first wife stresses that she is virtuous, dutiful, and never plays tricks that has “two sides and three knives.” However, when Bao places the child in a chalk circle between Zhang and Mrs. Ma, and orders them to pull the child toward themselves, Zhang relinquishes the attempt, unable to bear hurting her child, while Mrs. Ma shows little compassion for the baby. Bao thus announced Zhang to be the true mother of the child and punished Mrs. Ma for her two-faced behavior.

Now, if a coworker pulled a Mrs. Ma on you, you can warn others by saying:

He can be two-faced. You should be careful when working with him.

这个人两面三刀,你和他共事要多加小心。

To comply in appearance but oppose in action 阳奉阴违

This chengyu is used to describe someone who is feigning compliance. It can be found in numerous works of ancient literature, including Qian Family Instructions (《钱氏家训》), a composite of the principles left by Qian Liu (钱镠), the king of the Wuyue Kingdom during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907 – 960), to his descendants. In one of the principles, he states: “(We should) to our best efforts set up relief homes and orphanages to help the poor, supervising the wet nurses to make sure they don’t feign compliance or bully the children.”

Should you ever discover that someone has pretended to obey orders without actually executing them, or even does the opposite, it’s the perfect time to use the idiom. For example:

Since being promoted, he only feigned compliance with the company’s regulations, and was eventually fired.

自从升职之后,他总是对公司的规章制度阳奉阴违,最终被解雇。