Colorado’s burgeoning 19th century Chinese communities were destroyed by racist legislation and riots. Now, the state is finally coming to terms with its past.

At the intersection of 16th Street Mall and Wazee Street in downtown Denver, locals are accustomed to hearing the echoes of baseball chants from nearby Coors Field. Long buried, and forgotten by most, are the ghosts of other cries. Amid the red-brick buildings at this exact location on October 31, 1880, white European rioters chased nearly 500 Chinese immigrants out of their businesses and homes, leaving one dead.

This marked the beginning of the end of the city’s Chinatown, but nearly a century and a half later, a project called Reimagining Denver’s Historic Chinatown, started by local Asian American associations, hopes to document the experiences of those who once called this part of the Rocky Mountains home. To understand why the Chinese left, it’s important to look at what drew them to the Centennial State in the first place.

Gambling for gold

Seeking economic opportunities promised by the California Gold Rush and the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, Chinese immigrants began arriving on US shores around 1849. According to the History Channel, 15,000 to 20,000 Chinese worked on the railroads, making up nearly 90 percent of that workforce. But as the work dried up, they began looking further inland for new opportunities.

Colorado, a territory until 1876, was considered untouched land that had the potential to bring untold wealth. Opportunists, including a sizable Chinese population, flocked to the Rocky Mountain region, hoping to use their skills honed in railroad construction and mining out west. Central City, a major gold mining area, proved a potent lure. Once described as the “richest square mile on Earth,” the place eventually yielded almost 1 million ounces of gold extracted from its mines.

“If anyone, including Chinese immigrants, were going to do mining in Colorado in the early 1870s, Black Hawk and Central City (both in Gilpin County) would have been two of the most prominent camps to go to,” David Forsyth, director of the Gilpin Historical Society, tells TWOC via email. Well over 100 Chinese are believed to have lived in Gilpin County at the time.

Read more about the Chinese diaspora community:

- Who are the Chinese Diaspora in Ukraine?

- The Forgotten Chinese Heroes in Europe During WWI

- The Erased History of the Chinese Who Built America’s First Transcontinental Railroad

Black Hawk is these days considered Colorado’s gambling mecca, where multistory resorts loom over the remaining old town below. Central City, just a 10-minute drive away, has retained much of its old charm. This was where “Celestials,” a name given to Chinese immigrants in the 19th century to reflect their Heavenly Kingdom (天朝) roots, settled.

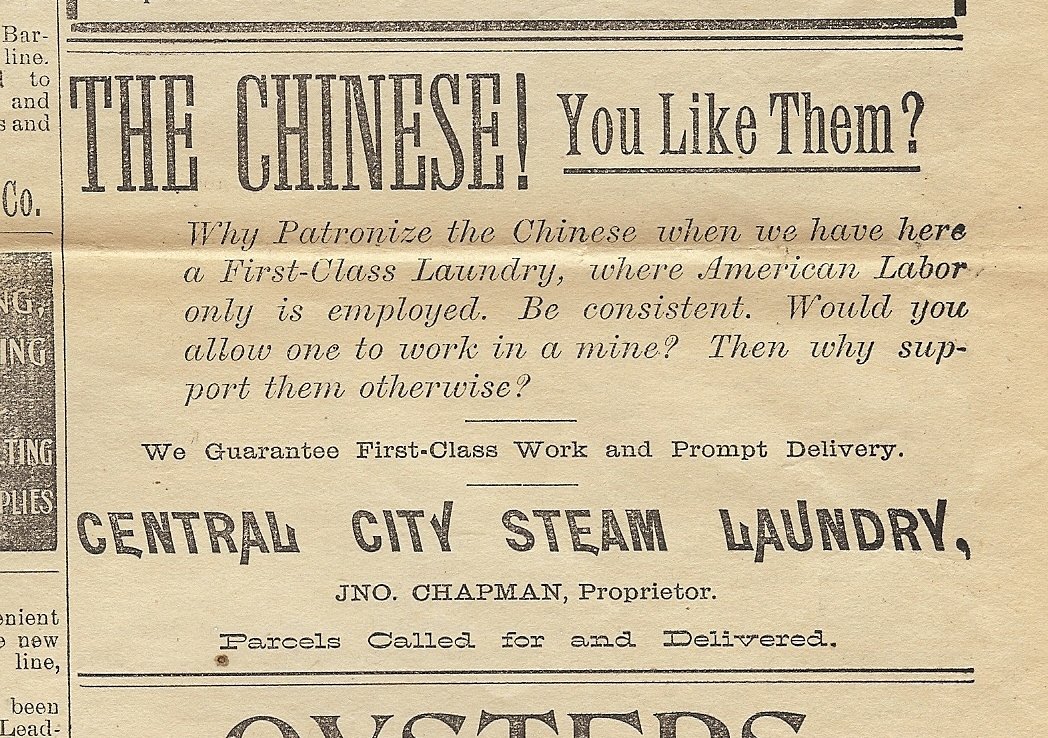

Dostal Alley became infamous as the “Oriental” section of Central City, as well as ground zero for a fire in 1874 that caused over 500,000 US dollars in damages. “Unfortunately, due to racial tensions at the time, many Chinese weren’t allowed to work in the mines, so they worked in laundromats on Main Street, where Dostal Alley is located, or did other odd jobs,” a guide at the Central City Historical Society tells TWOC. The majority of the downtown business district—around 150 buildings, mostly built from wood—burned down in the blaze. Today Dostal Alley is home to smattering of eateries, including a pizzeria and brewery, with little that reflects its fateful past.

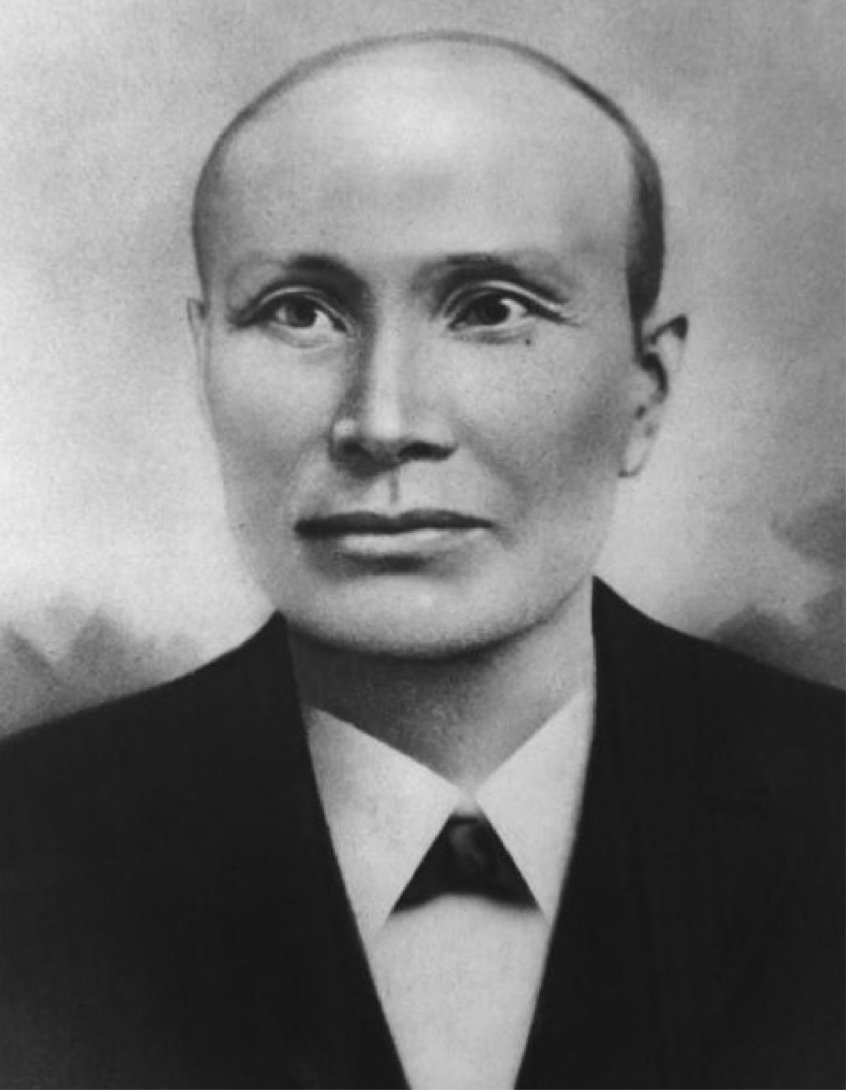

The Gilpin History Museum recently ran a small exhibit showcasing an assortment of newspaper clippings on the major fire, all featuring different explanations of its cause. Reported origins include celebrations following the birth of a Chinese child, “heathen religious ceremonies,” a funeral service, and laundry that caught on fire—all squarely putting the blame at Chinese immigrants. Only one man saw things differently: In a piece for the Colorado Daily Chieftain, Chin Lin Sou, a tall, prominent, blue-eyed Chinese businessman often recorded as speaking fluent English, stated that a faulty flue was the true cause of the fire.

“Chin’s influence might best be felt after the 1874 fire when a lot of people blamed it on various Chinese religious or social rites,” Forsyth says. However, “when Chin Lin Sou announced that a chimney fire was to blame, pretty much everyone accepted it, no more questions asked.”

A prominent Chinese immigrant in Colorado’s history, Chin arrived in the US from Canton (now Guangzhou) in 1859. After first working as a foreman on the railroads, he moved to Central City following the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. He later hired Chinese crews to work the mines he had claims on in Clear Creek, Black Hawk, and South Park. Despite Chin’s strong ties in Central City and his ongoing assistance to his countrymen, the 1874 fire and ensuing racial tensions would cause Chinese workers to disperse to nearby areas. In 1880, Chin and his family did so too, relocating to Denver’s Chinatown.

Massacres in the mountains

From the 1870s to the turn of the century, racial discrimination toward Chinese steadily grew, with notable race-related aggression in Colorado mountain towns playing out in Nederland (1874) and Leadville (1879). More than 150 race riots are estimated to have occurred across the US around this time. It was just north of the Colorado border, in Rock Springs, Wyoming, that one of the biggest riots and massacres of Chinese took place.

At the time, the Union Pacific Coal Company had been employing a mixture of Chinese and white labor in the area’s coal mines. Increasingly larger numbers of Chinese miners, often willing to work more treacherous mines at cheaper rates, began to arrive, eventually establishing a small Chinatown. But the community wouldn’t last long.

“There was already a general sense of distrust and feeling of animosity towards Chinese in the US,” Jennifer Messer, museum director of Rock Springs Historical Museum, tells TWOC over the phone. “Rock Springs had these coal mines that the Union Pacific Coal Company absolutely wanted to make the most of. They didn’t want unions…and there was a group of Finnish miners who really wanted to unionize. There were agitators and articles being published to keep things stirred up. It really was a powder keg.”

On September 2, 1885, a dispute erupted underground after disgruntled Finnish miners tried to claim credit for work on a portion of a desirable coal mine project initially completed by unpaid Chinese miners. “That was the flame,” says Messer.

The scuffle made its way above ground, with more anti-Chinese rioters quickly piling on the rapidly outnumbered Chinese. Twenty-eight Chinese miners would be killed as the fight moved over into Chinatown. Though federal troops were called into Rock Springs, they didn’t arrive before the more than 500 Chinese had been driven out and their once vibrant community burned down. Most moved to surrounding cities such as Evanstown and Green River, looking for safety and a fresh start. Troops remained in the area until 1898, and the U.S. government agreed to pay China reparations of around 150,000 dollars (4 million dollars today) for the horrific incident.

Unfortunately, the hatred against Chinese mining communities manifested itself in more than isolated bouts of brutality. “There are just pages and pages [of articles and reports] of violence against Chinese in the inner-Mountain West,” Messer says.

A Chinatown remembered

On June 29, 1869, the Colorado Tribune announced the arrival of the state capital’s first Chinese with the derogatory headline, “He’s come—the first John Chinaman in Denver.” A year later, more immigrants would come, following the passage of legislation by Colorado specifically aimed at encouraging Chinese to work the mines.

Denver saw its Chinese population swell to nearly 1,400 by the 1880s, which resulted in new businesses such as laundromats and gambling institutions. The Chinese district, bounded by Wazee, Market, 15th and 20th streets, would take on the moniker Hop Alley in reference to its once-popular opium dens (Denver had 17 by 1880).

But despite the local government actively recruiting Chinese labor, anti-Chinese agitation spread, with the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News stating on October 23, 1880, “California is already ruined through Chinese labor, and Nevada is seriously injured, and now Colorado is threatened with the same disaster.”

By that time, race-baiting was being employed at a national level. “First and foremost, there was the racist ‘Chinese Question,’ which asked whether more Chinese should be allowed to enter the country to compete with whites in a precarious economy and threaten the identity of a predominantly white country,” William Wei, a history professor at the University of Colorado, tells TWOC via email. “Second, the 1880 presidential election made the ‘Chinese Question’ a campaign issue, exacerbating the polarized politics at the time.”

The Chinese were specially attracted to Denver for its broader offerings of goods and services. Animosity toward them only grew alongside their numbers. On Halloween of 1880, a run-of-the-mill bar fight at John Asmussoon’s Saloon between two Chinese and a group of white men spiraled out of control. It culminated in 3,000 to 5,000 anti-Chinese rioters—a tenth of Denver’s population at the time—attacking the city’s Chinatown and attempting to drive out its 450-plus residents. During the conflict, a mob lynched a Chinese laundryman named Look Young and seriously injured many more.

Denver’s “Bloody Riot” garnered nationwide attention, especially since it occurred two days before the 1880 presidential election. A once prospering Chinatown was decimated, and despite many Chinese Denverites being determined to rebuild their homes and businesses, anti-Chinese sentiment only gained steam. Two years after the riot, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in Washington, preventing Chinese immigrants from establishing families in America until its repeal in 1943.

In April 2022, Denver’s then-mayor Michael Hancock publicly apologized for the incident and past harm done to its Chinese residents, making Denver only the fifth major US city to do so. Alongside the apology, three new historical plaques were installed in the former Chinatown area—including at 1620 Wazee Street, the site of the bar fight that ignited the Denver Chinatown riot—as a reminder of its tragic end.

As of June 2024, there are fewer than 50,000 Chinese living in Colorado, a small number in comparison to the millions that live in US coastal cities. Nevertheless, a sandstone monument for the 28 Chinese miners killed in Rock Springs, a newly completed mural, and plaques commemorating various notable events and Chinese individuals are small examples that the Rocky Mountain region is trying to engage with and reflect on the tragic history tied to its soil. Maybe, one day, a bustling Chinatown will exist here once again.