Long believed to be a myth, Chinese jade burial suits symbolized ancient nobles’ pursuit of eternal life

During the tension-filled years of the Cultural Revolution, China began a number of national defense projects against a potential foreign invasion. But on May 22, 1968, while blasting rock to build an air-raid shelter near the top of Lingshan Mountain in Hebei province, a team of Chinese soldiers discovered something extraordinary: the undisturbed, 2,000-year-old tomb of Liu Sheng (刘胜), a king of the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE), and his wife Dou Wan (窦绾), who both died in the second century BCE.

The tombs were grand in scale, built like luxurious underground palaces. Perhaps due to their isolation, they remained safe from looters and preserved over 10,000 cultural relics, including weapons, drinking vessels, and incense burners. But the most exciting artifacts were two intact “Golden Thread Jade Burial Suits (金缕玉衣),” near-legendary objects described in classic literature but never before seen in living memory. For years, people debated what they looked like, or whether they really existed. “The jade garment unearthed from the tomb of Liu Sheng has solved the mystery of jade clothes,” Lu Zhaoyin, an archeologist on the team sent to excavate the tombs, told the Beijing Daily in a 2018 interview.

Read more about archeological discoveries in China:

- Tomb of a “deposed emperor” in Jiangxi provides new clues to the history of the Han dynasty

- At the forefront of China's booming underwater archeology field

- Mystery of the Sanxingdui Culture from 3,000 years ago

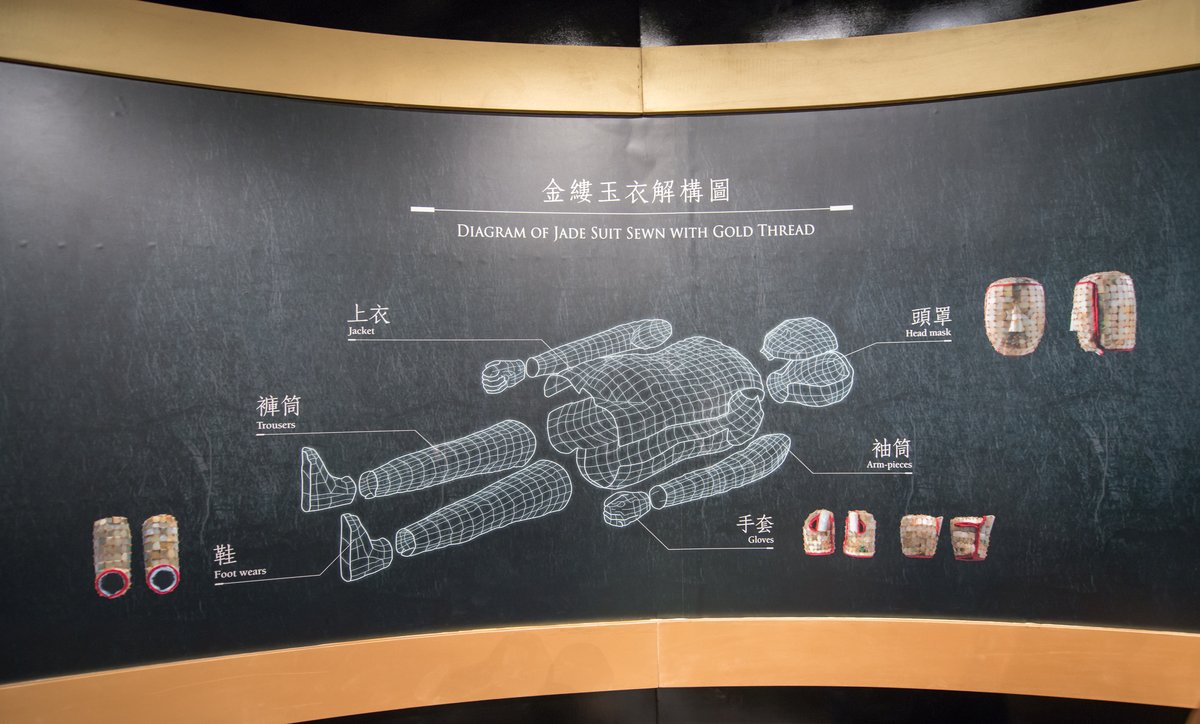

Elderly people in China traditionally prepare special clothes to be buried in, known as shouyi (寿衣, which directly translates to “longevity clothes”), before they pass. However, nobles of the Han dynasty preferred more elaborate burial attire, like the jade burial suit, also known as “jade coffin (玉匣).” Made entirely of jade pieces linked with gold, silver, or copper threads, these suits were a mark of high status. Liu’s jade suit had 2,498 jade plaques and 1,100 grams of gold thread, while his wife’s had 2,160 jade plaques and 700 grams of gold thread.

From the outside, the shape of the jade suit is almost identical to the human body. The top part consists of a head cover and mask, forming shapes of eyes, nose, and mouth. The upper garment is composed of front and back pieces, as well as left and right sleeves, all of which are made separately. The front piece is made to represent a broad chest and protruding abdomen, while the lower end of the back piece is shaped like the human buttocks. The trousers are composed of two leg tubes, also separately made, and the hands are formed in the posture of a clenched fist, each holding a semicircular jade ornament.

China’s reverence for jade dates back to its earliest civilizations. Mined from mountain streams and possessing an intriguing translucence, jade symbolized noble qualities such as purity and resilience. People wore jade ornaments on a daily basis. At the sites of the Liangzhu culture, located near present-day Hangzhou, Zhejiang province and regarded as one of the oldest civilizations in the world over 4,000 years ago, archeologists have discovered numerous jade ornaments and discs. The Book of Rites (《礼记》), a collection of texts mainly published in the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) on the society and politics of the Zhou era (1046–256 BCE), recorded that, “A gentleman shall not part with his jade without cause (君子无故,玉不去身).”

Besides its value to the living, ancient Chinese also believed that jade could preserve the body from decaying. Ge Hong (葛洪), a famous physician and Taoist from the Jin dynasty (265–420), stated in his book Baopuzi (《抱朴子》): “If gold and jade are placed in the nine orifices, then the dead will be immortal (金玉在九窍,则死人为不朽).” The so-called “nine orifices” refer to the eyes, mouth, ears, two nostrils, genitalia, and anus. Correspondingly, jade burial suits often included components like eye covers, nasal plugs, earplugs, mouthpieces, small boxes covering the genitalia, and jade anal plugs.

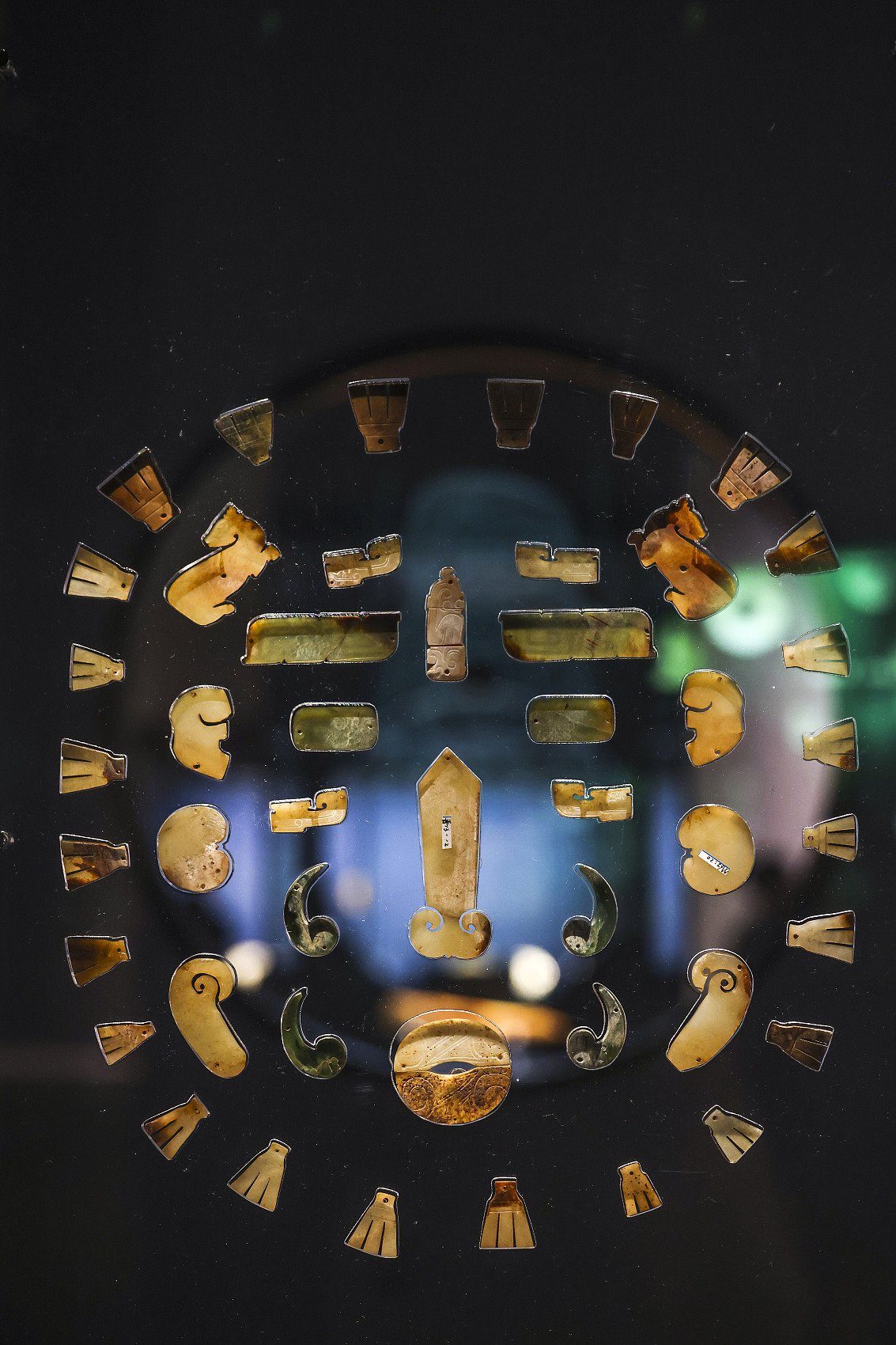

The tradition of jade burial can be traced back to the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE). At that time, the jade objects buried with the deceased were called “Jade Face Covers (缀玉覆面),” consisting of jade pieces of various shapes sewn onto fabric and arranged to resemble the facial features of a person. In 1990, archeologists working at the Guo State Tombs in Henan province excavated a jade cover composed of 14 jade pieces from the Western Zhou period, proving that the custom already existed in that era.

During the Han dynasty, lavish burials were common. The use of jade to enshroud the dead peaked, evolving into complete jade suits. Historical records show that emperors were laid to rest in gold-threaded jade suits; princes, princesses, dukes, marquises, and the emperor’s consorts in silver-threaded jade suits; and emperor’s sisters and other nobles of a slightly lower rank in bronze-threaded jade suits. But as Liu Sheng and Dou Wan lived in an earlier period when jade suit hierarchy was less rigid, they were allowed, as a feudal lord and lady, to be buried in gold-threaded jade suits.

As we now know, jade cannot prevent a corpse from decaying. To date, no jade suits found by archaeologists have managed to preserve the flesh. Moreover, the jade suit’s high value attracted tomb raiders, leading to the destruction of the mausoleums and even the bodies. The Records of the Three Kingdoms (《三国志》) recorded: “All the Han dynasty tombs have been robbed and even burned to retrieve the jade suits and the gold threads, leaving bones completely gone (汉氏诸陵无不发掘,至乃烧取玉匣金缕,骸骨并尽).” Accordingly, Cao Pi (曹丕), Emperor Wen of Wei, banned the use of jade burial suits in the year 222, ending a 400-year-old funerary fashion in China.

Since the 1968 discovery of Liu Sheng’s tomb, about 20 sets of Han dynasty jade burial suits have been unearthed in China in provinces as far apart as Henan, Jiangsu, and Guangdong. However, these artifacts remain incredibly rare, so much so that they have proved a valuable target for forgers. Xie Genrong, a Beijing property developer, forged one gold-threaded jade garment and one silver-threaded jade garment and used them as collateral to secure a loan of hundreds of millions of yuan from China Construction Bank in the early 2000s.

To prove their authenticity, Xie presented the bank with an evaluation report supported by five experts including Yang Boda, the former deputy director of the Palace Museum; and Shi Shuqing, the former deputy director of the National Cultural Heritage Appraisal Committee. The report valued the garments at a shocking 2.4 billion yuan. But instead of using the money for real estate projects, Xie spent it on personal luxuries and left the buildings unfinished. In 2008, the police arrested Xie and two bank representatives on fraud charges. Although the five experts were suspected of taking bribes from Xie, they were not charged due to insufficient evidence.

Although jade burial suits failed to grant immortality to their owners and, in Xie’s case, led to tragic ends, they remain a testament to ancient craftsmanship and beliefs. Today, we can still admire Liu Sheng and Dou Wan’s exquisite jade suits at the Hebei Museum, appreciating their intricate design at a safe distance.