The work of Guangzhou-based photographer Yan Jiacheng captures life on the fringes through documentary and conceptual methods

As night falls over the outskirts of Guangzhou, 31-year-old photographer Yan Jiacheng is taking one of his after-work strolls. Towering residential high-rises line one side of the street, their windows glowing warmly against the sky. On the other side, darkness extends out into the countryside, with the next village some distance away. This stark contrast between urban illumination and rural obscurity defines the setting for his ongoing series “Night in the Suburbs,” documenting urban-rural nightlife in a makeshift public space.

Yan is a documentarian straddling the lines between urban and rural life, and fringe spaces such as this one, not far from his apartment, are where he finds both inspiration and community among the people whose daily lives he captures through his lens.

“When I had just moved here, there was no street, only mud. But around April or May that year, they began constructing the street,” Yan recalls. “There were no cars here at first, so people started using this as a public space to hang out.”

Today the street is a hive of evening activity. Vendors sell snacks and fresh juice out of cars and small stalls. Locals cram around small tables under the streetlights. “The business here is so good, that this seller suggested I start selling ice cream with him,” Yan tells TWOC, motioning in the direction of a middle-aged man who is soliciting his sweet goods in a thick Cantonese accent.

Initially, Yan was hesitant to share his pictures documenting such common scenes from the local neighborhoods. But when he posted the images on Weibo, they were quickly shared more than 4,000 times.

Yan now has 31,000 followers on Weibo, and while the engagement from his growing online audience has boosted his confidence as an “amateur photographer,” the demands of social media have also created a new set of challenges—and perhaps even increased the distance between him and the subjects he strives to connect with.

Read more about contemporary Chinese artists:

- Healing Strokes: A Gen Z Artist Explores Personal Pain and Historical Trauma

- Beyond the Frame: Shuare Shizhu’s World in Wide Strokes

- Too Rich: Wealth and Peril in Huang Heshan’s City Dreamscapes

Sudden realization

Yan’s journey into photography began unexpectedly. In 2016, after graduating from Jinan University with a degree in Chinese, he found himself caught in the relentless demands of China’s white-collar professional world, regularly working overtime and overnight at a state-owned enterprise. “The work was taking a toll on me at that time and I wanted to do something I believed to be valuable, to make myself feel more valuable somehow, so I was looking for a new hobby,” Yan recalls.

This search led to a moment of realization—or dunwu (顿悟)—a Buddhist concept of sudden enlightenment, he explains. While waiting at a high-speed rail station in Shenzhen, Yan took out his camera and started taking random photos of people, including a high-contrast black-and-white image of a middle-aged man in the waiting hall boasting a wide smile. The next day, Yan went to Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province, and continued his series of black-and-white images, capturing the daily routines of the city’s delivery workers.

Away from the numbing busyness of his corporate job, something clicked for Yan as he documented the fleeting, mundane moments of city life. “I suddenly felt that I understood how to take pictures, that I could take proper pictures and pursue this more seriously,” he says. This moment marked the beginning of his journey into more serious photography, driven by a desire to capture life’s fleeting moments in a way that felt authentic to him.

Yan’s early works were characterized by their spontaneous nature, capturing everyday life with a keen eye for detail. His series “Nighttime Advertising Lightbox” and “Deluxe Hotel” reflect his fascination with the transient and often overlooked aspects of life on the fringes of society.

In the “Nighttime Advertising Lightbox” series, Yan found inspiration in the illuminated advertisement boards at bus stops in his Guangzhou neighborhood. These “lightboxes,” often empty and emitting a stark white light, transformed into makeshift photography studios as Yan documented the diverse array of people passing by. From elderly women carrying groceries to young couples on evening strolls, Yan captured the essence of urban-rural fringe life in these fleeting, illuminated moments.

The “Deluxe Hotel” series cast his gaze beyond his local surroundings, capturing the lives of Chinese migrant workers in Singapore’s hotel industry. The project also meant looking inward, as it draws from both his family’s and his hometown’s experiences of labor migration.

Yan grew up in Lianyungang, a port city in Jiangsu province. His father was a vague presence throughout his childhood, doing long stints of work in other parts of the country and even abroad, like many others from Lianyungang. “When I was a kid, I always wondered what their lives were like,” says Yan. Those questions drove him to follow some of them abroad, documenting their daily routines as migrant workers with a sense of intimacy and immediacy.

For several years, Yan has been contemplating a project about the significance of wedding pictures. “When my parents got married, there were no wedding pictures, for financial and other reasons. Many years later, my mom went to take some wedding pictures all on her own. I realized a lot of women where I’m from do this—not just her,” he tells TWOC. The phenomenon fascinates him. “I want to collect some of these images and see how to make that a project. I’ve been thinking about that for a few years now, but every time I go back to my hometown I barely have any time, and I also don’t know what I want it to look like. So there is this idea in my head, but I haven’t really done much with it yet.”

Extending reality

As Yan’s understanding of photography evolved, so did his approach. Moving away from purely observational work, he began to explore the possibilities of image manipulation—altering and stitching images together to create new narratives and visual metaphors.

Two of his series, “This is a Long Story” and “Spring Festival Travel Rush,” feature long composite images of people cramming onto Chinese subway cars, X-ray conveyor belts sliding forward inside train stations, and city workers cleaning the roadside railing. US photographer Michael Wolf’s famous shots of residential towers in the Hong Kong skyline come to mind, or the German photographer Andreas Gursky’s large composite images of a famous residential block in Paris or seemingly endless shelves stacked with products in a 99-cent store in Los Angeles—not so much photographs in the classical sense, but rather visually distilled metaphors for larger cultural phenomena like post-modern uniformity and excess. “I don’t think a picture is only supposed to be what comes out of the camera,” says Yan. “If the camera already has limitations, why should the person behind the camera also limit themselves?”

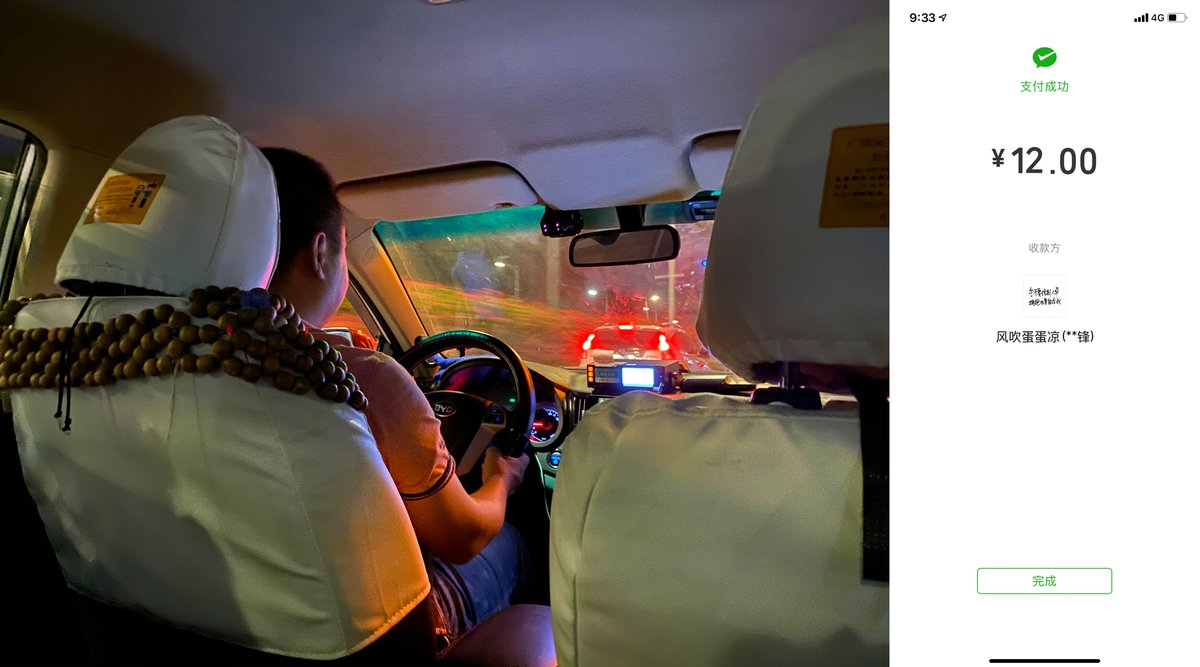

“Everyone Has an Online Nickname,” shot in 2020, serves as a transitional series bridging his earlier street photography with more conceptual work. In this series, Yan combines his photographs of Chinese taxi drivers with screenshots of their WeChat nicknames, showing the often funny and unexpected online personas hidden behind WeChat payment QR codes. “Our names are given by our parents, something we are born with,” he says. “But in the internet age, everyone has the right to choose a name, reflecting their view of the world or themselves.”

Yan’s photography has since taken an even more conceptual turn. With the demands of his day job at a state-owned telecommunications company limiting his time for street photography, practical constraints have pushed him to explore new creative avenues. “I like coming up with ideas and then turning those into images,” he tells TWOC.

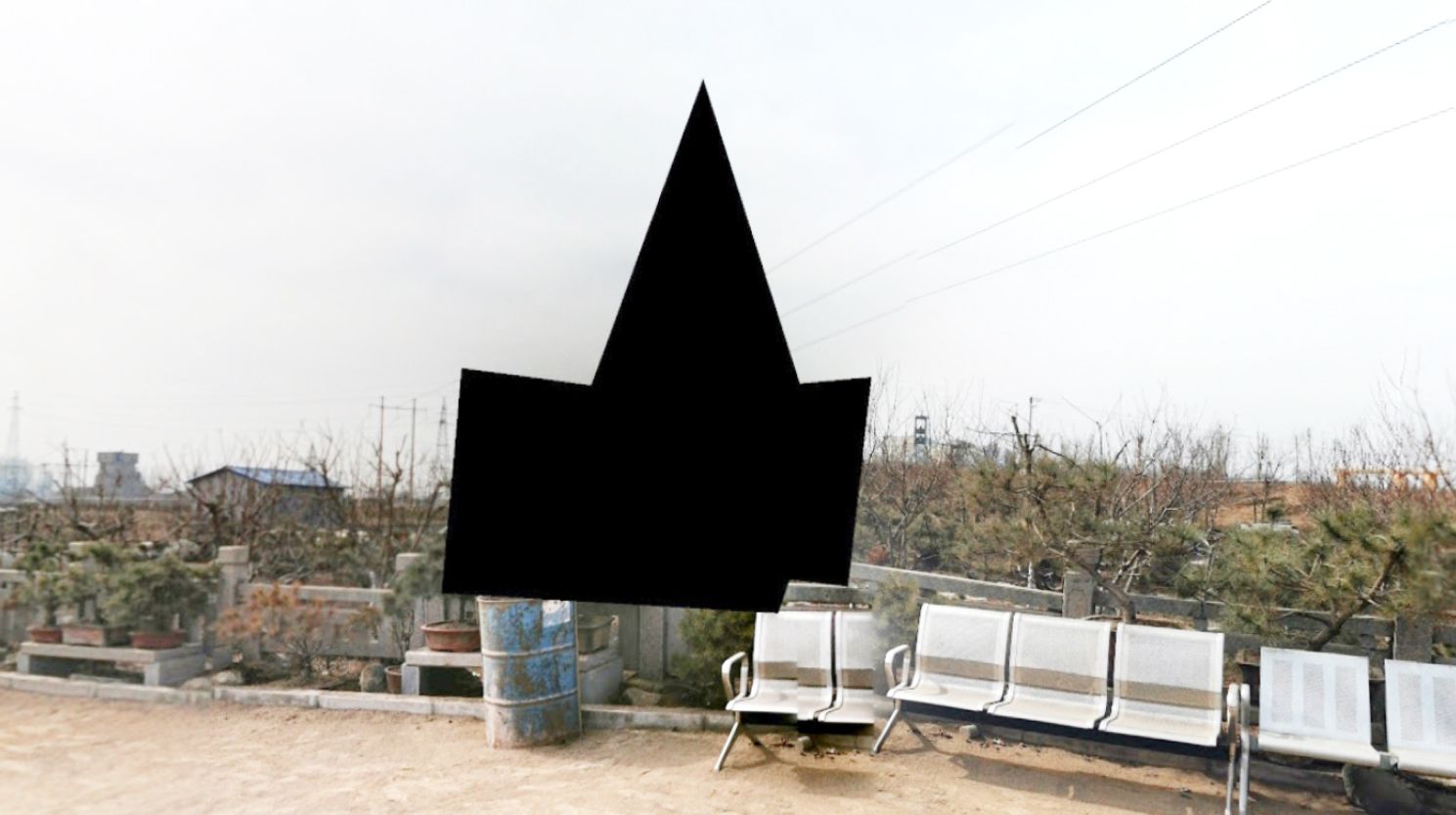

Compared to his street photography, Yan’s conceptual works are often created from a distance—physically at least. A lot of the images feature strangers he never met in person, created using visual material he sourced online or sent to him by friends. In his series “Group Photo Searching,” Yan highlights the gender disparity in leadership positions by finding stock group photos of Chinese employees and obscuring male faces with simple white. In another series, titled “The Hollow of Google Street View,” Yan uses images from Google Maps to create composites featuring “blind spots”—black geometrical shapes at the center of the image—beyond the capabilities of the Google image-stitching algorithm. For “Traffic Police Notification Platform,” Yan tapped into the official surveillance imagery released by local traffic enforcement authorities. He collected and curated hundreds of images showing diverse and sometimes humorous ways people navigate urban spaces on scooters—including a young man apparently practicing basketball shots, and a middle-aged woman likely returning from a grocery haul, with what looks like a bunch of raw red meat stuffed into her scooter’s front basket.

Social (media) anxiety

The demands of social media and the anxiety of maintaining a regular online presence have contributed to Yan’s conceptual shift. With much of his time spent working in the office, he turns to using screenshots to create images to ensure he can produce—and post—content regularly. This helps him alleviate the anxiety that arises from feeling unproductive and the pressure of keeping his followers engaged.

Despite the pressures to regularly publish online—and lack of recognition from the high-brow art world in China—Yan finds solace in the connection he builds with his followers. “In the Chinese art world, resources are concentrated in the hands of small groups of people that are very hard to break into. But when you do creative work, you’ll realize that posting your works for an audience online may already be enough. I have some people paying attention to my work and I don’t think that’s worth less than showing my works in exhibitions,” he says. Even so, this direct connection with a growing online audience has created some opportunities to do exhibitions abroad. Within China, however, Yan has little interest in socializing and politicking to chase the same. “I’m not really interested in trying to get into these social circles,” he says.

As Yan continues to navigate the tensions between a full-time day job and his after-work creative endeavors, and between his “amateur” identity and a more professionalized set of ambitions, his focus has settled on creating harmony between his various pursuits. “I think life is a lot about finding that balance,” he tells TWOC. “The balance between work and leisure, between creative work and money matters, the balance of time—spending time with my family, my girlfriend, and making my art.”

Images courtesy of Yan Jiacheng