Public K-pop dance performances are growing in popularity in China, but does their proliferation point to female empowerment or the perpetuation of the male gaze?

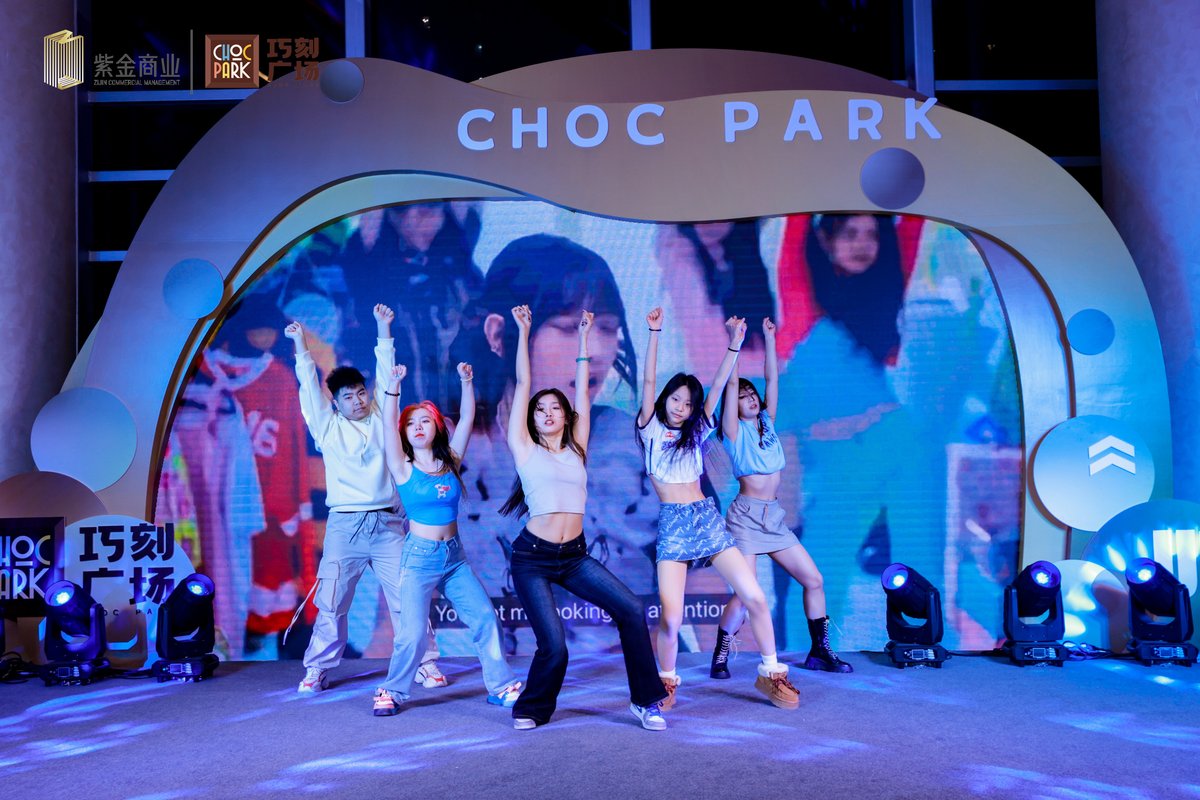

Tami Jiang, a 26-year-old high school teacher, tends to stay out of the spotlight. However, this April, in a bustling shopping mall in central Beijing, all eyes were on her when she and her fellow dancers captivated the crowd with choreography to the latest viral K-pop hit, “Sheesh.”

“I’ve never looked better on camera!” Jiang chirped to a friend after reviewing a video of her performance. Jiang, who agreed to be interviewed under a pseudonym, soon posted the video to Xiaohongshu, a Chinese social media platform especially popular among female users. Jiang’s routine joined the 580,000 other dance performance videos under the hashtag “luyan (路演),” or roadshow, shared by enthusiasts across the platform.

On the Chinese internet, roadshows refer to public dancing events that are filmed, edited, and later uploaded to social media. Originally a way for amateur dancers to imitate their favorite K-pop idols, roadshows have grown into a lucrative business thanks to the traffic they can generate for public spaces, especially bars, shopping malls, and live houses. Event planners usually provide the venue and equipment, while participants deliver their best performance for free in exchange for a unique star-like experience. But just like real stardom, the attention they receive doesn’t always come from appreciating fans.

The allure of these glamorous performances is driving the rising demand for roadshows among young women in China. Milky Liu, a second-year graduate student in industrial design engineering at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, says she was immediately drawn to the hobby in high school after coming across a K-pop audition show on TV. “The girls look breathtakingly sparkly on stage. They look so put together that I wanted to be one of them too,” says Liu, who requested to use a pseudonym. The show prompted her to learn more about K-pop culture and practice the choreography of viral songs. She soon attended her first roadshow performance with people she met in a related group on China’s ubiquitous messaging app WeChat.

Read more about idol culture in China:

- Is China’s Boy Band Boom Over?

- When Fresh Meat Turns Rotten: How Idols Fail

- Tiny Fresh Meat: Inside China's Child Star Factory

Liu’s experience is part of a growing trend. Kpop Star, a Shanghai-based event-planning organization, tells TWOC that their WeChat groups have accumulated over 20,000 participants across 16 cities in China since May 2023. Most of the members are teenage girls and university students, who tend to have more spare time and little financial pressure. The company’s garishly pink roadshow recruitment poster reads: “Anyone at any age interested in K-pop dance is welcome to come and have fun.”

Roadshows’ social aspect is another driving force behind their popularity, with gatherings often fostering genuine friendships among like-minded strangers. “No complex introduction, no testing waters. We are simply brought together by the love of the same song,” Yang Qianyi, a recent graduate from Beijing’s Communication University of China, tells TWOC. Participants often refer to these serendipitous meetings as “carpooling (拼车).”

Liu says her experience has opened her eyes to various life possibilities and introduced her to girls from a diverse range of backgrounds. She once participated in a show with a sixth grader who claimed to teach dance classes during her free time, earning even more money than Liu, who was interning at an internet startup at the time. Liu says the warm and chatty young girl helped her open up to others and express herself more freely.

However, the pressure to maintain a flawless appearance amid such camaraderie can be overwhelming for some, creating a paradoxical dynamic of both support and scrutiny. “It’s natural for good-looking girls who dance well to stick together. But those who don’t fit into the typical idol image can feel left out,” says Tao Xi, a freshman at Nanjing Normal University. Tao has been attending roadshows for more than a year and is now helping Pink Signal, a professional roadshow agency in Nanjing, to plan events. She recalls an oversized girl in her circle being judged for her body shape, amateur dance moves, and revealing clothes. “That’s the harsh reality. Even when people notice that [others are being judged], they just pretend not to know and go along with the game. Women are so used to conforming to certain beauty standards,” laments Tao.

Ippara Baratjan, a feminist influencer from Xinjiang, points out that despite many roadshow dancers asserting their performances as a form of self-expression and agency over their bodies, they still unconsciously conform to mainstream beauty standards, such as dieting before shows to attain a slimmer figure.

“When it’s impossible to escape the influence of the prevailing aesthetic standards, very few people can truly immerse themselves in dance performances without caring about their appearance and physique in front of the camera,” says Baratjan.

Liu echoes these sentiments: “Once you’re on stage, you start to worry if a hairpin is in the right place, if a bow is tied, if your face looks perfect on camera, and whether your thighs are too thick.” She adds that some might feel more self-conscious when they compare their looks to the idols they are trying to imitate.

To help her fellow dancers overcome self-doubt, Liu has started a series of posts on Xiaohongshu to explain how idols’ costumes are able to create the illusion of a perfect body. For example, she outlines how dresses are cropped short specifically to show off waistlines and tube tops never slip because they are taped to the body. “[The image of a perfect idol] is the artificial result of a whole team of stylists and designers. It’s their full-time job, but not ours,” Liu tells TWOC.

However, the scrutiny doesn’t stay within the roadshow community—it’s compounded by external judgment from audiences and online critics. Many admit to receiving hateful comments in their roadshow posts. Tao received her first negative comment judging her appearance on a video she posted on Douyin (China’s version of TikTok). It was only her second show. “Even my dance teacher gets bullied on Douyin for all her skills and confidence. People will judge your appearance for no reason,” says Tao. She has quit the platform since then. She says it took her a while to get her confidence back, but she was eventually able to ignore the criticism and return to the stage. “If [the haters] are so capable, why don’t they show their face in front of the camera?” Tao now posts mainly on Xiaohongshu, where she often receives encouraging notes from other women.

While Tao has learned to block out online harassment, abuse offline can sometimes be harder to avoid. Tao recalls that a male onlooker was caught secretly filming up a performer’s skirt during a roadshow she helped organize last year. After staff from the organizing team confronted him and threatened to call the police, the man ranted and swore before reluctantly deleting the video. “There is little we can do. K-pop groups feature fancy makeup and costumes. Perhaps some men think that the girls dress like that deliberately to impress [them].”

Baratjan, the feminist influencer, agrees that there is often a fine line between “elegant sensuality” and “seductive allure.” “Female idols, especially in K-pop, are usually selected, transformed, and presented to the public as a sex symbol,” she says. It’s therefore not uncommon for some audience members to perceive roadshow dancers in the same light.

On the other hand, Yoyo Ye, a K-pop fashion blogger on Xiaohongshu from Guangdong province, argues that amateur dancers do have more autonomy: “While real idols have to conform to certain concepts and looks designed by their entertainment companies, ordinary girls get to decide how they want to look and what they want to convey.” According to Ye, roadshows allow women to try out different styles and explore different appearances of their choosing. Despite this added freedom, it can be hard to shake mainstream trends: The majority of Ye’s posts on Xiaohongshu consist of affordable outfit choices similar to those worn by idols on stage.

“We must be cautious, as long-term internalization might lead us to adopt male standards of ‘beauty’ and ‘femininity’ as our own preferences,” warns Baratjan. She is happy to see more dance performances on college campuses where girls, while still dressed up, focus more on showcasing their healthy physiques with self-assured expressions through powerful routines. “I think it’s progress that women have more opportunities to express themselves, but [the development of gender equality] in society has yet to keep up.”

In lieu of being able to eradicate the male gaze, roadshow dancers have resorted to other means to avoid unwanted attention. Enthusiasts like Yang and Jiang now avoid performing sexy dances in public spaces and instead choose songs that advocate female empowerment from Korean groups known for feminist concepts like XG and TRI.BE. While Tao remains indiscriminate when it comes to song choices, she vows that she and her friends won’t give the audience any wrong ideas thanks to their ability to dance with (as a popular online meme goes) “the most steadfast expressions, as if we were looking to join the Party.”