How a mural artist invents and builds deities inspired by the spiritual customs of Quanzhou

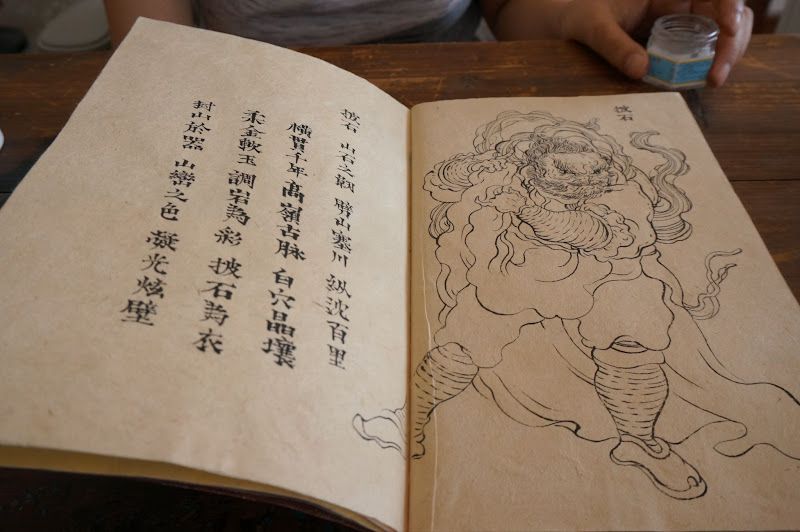

Inside a bustling wood carving workshop, a mighty god greets visitors by the door. Surrounded by dozens of tinier Buddha statues, this half-finished wood sculpture stands out. With an unobtrusively staid face and tentacles sprawling from the torso, it leans forward as if about to charge, exuding a dynamic energy rare for deity statues in China.

“This is Zhaohai,” mural artist Wen Na told TWOC on a sunny morning this July, gazing at the sculpture’s pale-yellow body yet to be colored.

Zhaohai, whose name literally means “lighting the sea,” is a sea god Wen Na made up when she was invited by a cultural center in Alassio, an Italian town by the Tyrrhenian Sea, to paint a mural there in 2011. Inspired by the misty, moonlit night view of the water, she created a god whose divine talent is to illuminate the ocean every night for the town.

Now, Zhaohai will join a lineup of 22 deities Wen Na imagined and had carved as part of a mega series of installations and murals, titled Canghaicuo, or “house that takes in the sea.” These works—still in the making—will be collected in a traditional village house in the coastal city of Quanzhou, Fujian province, which will be open to visitors this October. Through this project, Wen Na, an artist known for creating otherworldly, cheeky, and sometimes uncanny deities from various folktales, mythology, or even pure imagination, finds new inspiration in Quanzhou’s rich religious and folk traditions.

Born into an artist family in Beijing in the 1980s, Wen Na, whose real name is Chen Xingxing, was initially more passionate about expressionist theater work like those from Pina Bausch. But after enrolling at Tsinghua University’s Academy of Arts & Design, she began exploring various artistic media, majoring in printmaking while illustrating all kinds of images and figures at her friends’ request.

If her earlier gigs were mostly for fun, the turning point for her career came abruptly, via a humble wall in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, China’s porcelain capital. In 2009, at the invitation of a local art center curator, Wen Na painted deities of wine, tea, and the Kitchen God on an abandoned wall dedicated to a local village restaurant. Before that, Wen Na had never brought the wild imaginings in her head into the world, and this was also the first time she had held a traditional Chinese brush to work directly on a wall. But once she started painting, Wen Na recalls, it all came naturally—three long-faced men in baggy coats holding a wine cup, a teacup, and food. The mural quickly received positive feedback from fellow artists.

Since then, murals have taken Wen Na from the artist enclave in Jingdezhen to a Chinatown in Mauritius, and beyond. She started to make magnetically beautiful, dramatic, and distinctive murals of personified deities, always weaving the traditional into the contemporary.

In a 40-meter long, four-meter-tall mural inside Beijing’s Guomao subway station in the center of the city’s commercial district, which attracted much media attention, she brought to life more than 60 gods in vibrant colors commuting amidst clouds, from a god of food delivery to a deity of project management—all divinities Wen Na imagined to embody the contemporary needs of China’s urbanites.

But Canghaicuo is by far her most challenging project, Wen Na says. Unlike previous work in which she relied on drawing and painting, “this is the first time that I am telling a story with such integrity and layers, not to mention using a huge group of statues to embody the idea,” she tells TWOC.

Part of the complexity has to do with Quanzhou itself, a coastal city newly minted as a UNESCO world heritage site in 2021. Facing the Taiwan Strait, this city was an ancient cosmopolis with vibrant multi-cultural traditions and a major crossroad for global maritime trade back in the Song and Yuan dynasties.

Various religions converged here. Even today, visitors can explore sites featuring belief systems from the homegrown Confucianism and Daoism to imported faiths like Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, and Manichaeism—though for some sites, only ruins remain today, and many temples were damaged during the Cultural Revolution. According to an estimate by the local government this year, there are currently 603 registered religious event spaces in the city and thousands of temples and palaces dedicated to folkloric beliefs.

Canghaicuo, Wen Na’s first project in Quanzhou, was commissioned by a tourism and cultural development company in Jinjiang, a county-level city under Quanzhou where she now lives and works. To her surprise, what started out as a quick gig turned into a three-year (and counting) project with a storyline that keeps evolving as Wen Na digs deeper into Quanzhou’s culture.

The folkloric traditions around deities in Quanzhou are not a fading cultural heritage. “We worship our local protector gods and other gods, so I have been familiar with the idea of deities since I was little,” says Huang Zunhe, a 27-year-old local deity sculptor who practices Daoism.

People in Quanzhou share a sense of intimacy with deities, says Cai Shuxiang, a Quanzhou native Ph.D. student at the Institute of Architecture and Urban-Rural Studies of Taiwan University. To some degree, temples and churches in Quanzhou function like community centers, she says. “You walk into a temple, and behind the main room you will find people playing mahjong.”

Seated on a tatami mat in a study tucked inside her workshop, Wen Na explains the attraction of Quanzhou for her work. “After I arrived, I found that the way people here look at gods is very much like my own philosophy,” Wen Na, captivated by the mundanity of faith in local people’s lives, tells TWOC. “It’s like, while we are chatting now, that small electric fan could be our little wind god,” she says, gesturing to the fan beside her.

Since 2020, she has been working with Chen Zenghuang, a local wood carver who brings the deities to life based on Wen Na’s prototypes.

Chen learned the skills from his father. In Jinjiang, his family is known for their long history of making statues of Buddha and local protector gods. Chen now manages the family business and oversees the production of statues sold to Min-speaking communities in Taiwan and Southeast Asia. He tells TWOC that the demand for deity statues has never waned, even among young people.

“It’s not superstition. People can find support and solace in them,” he says. “Everyone has times when they feel helpless. Some turn to idols, some turn to people, and some turn to gods.”

For inspiration, Wen Na and her colleagues often tour villages in Quanzhou, collecting various folklore and visual elements as materials for Canghaicuo. For example, some of Wen Na’s characters borrow the colorful headwear and exaggerated facial expressions often seen in Quanzhou’s traditional puppet shows.

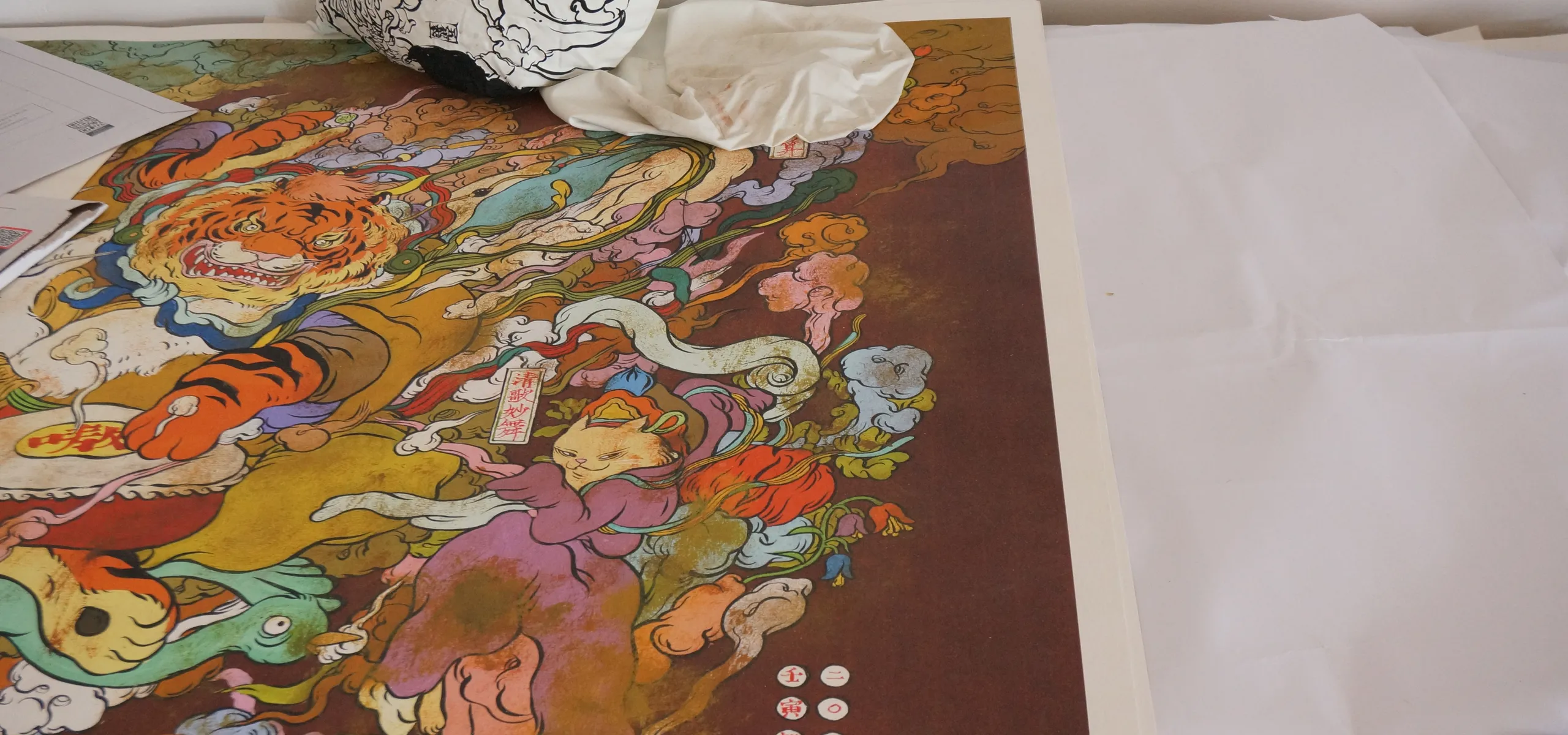

In the samples of colored designs based on her sketches that Wen Na showed TWOC on Photoshop, the main mural in Canghaicuo weaves together a story about Quanzhou’s migration history and its secularized contemporary life. In a rolling landscape, she paints crisp silhouettes of mortals, deities, and animal-shaped spirits—Chinese sea goddess Mazu, Jesus, local people, tradesmen from the Middle East, feral monsters—either singly or in scenes of festive interaction on waves of peaceful psychedelic cloud which represent heavenly blessings.

In Wen Na’s plan (the fourth version she has prepared so far) for the presentation of the project, the 22 deity statues she created, whose figures and background stories are also part of the mural, would join the project in physical form with Chen’s help. These sculptures will stand in front of the mural, almost like a pantheon mixing local cultural histories and modern myths created by the artist.

“I am trying my best to reflect the city’s rich tradition,” says Wen Na. “And I am doing it in a way that I hope the project can be something that will be passed down through generations.”

Images provided by Ye Yuan and Wen Na

Sculpting Divinity: The Artist Creating Gods from Ancient Folklore is a story from our issue, “Small Town Saga.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.