From Christians in the Tang dynasty to all-night parties in early 1900s Shanghai, the Western holiday has a longer history in China than most people think

China is credited with inventing many things—some (like soccer and golf) less plausibly than others—but...Christmas? An essay by poet Li Bai (李白), who lived in the eighth century, mentions a celebration called 圣诞之节 (Shèngdàn zhī jié), a term that sounds suspiciously similar to the modern Chinese word for Christmas, 圣诞节 (Shèngdànjié).

The truth is, “Christmas” is about as Chinese as the city of Shangri-la in Yunnan really is a mythical lost kingdom: that is, in name only. The Christian holiday wasn’t widely known as Shengdanjie until the 1920s, with shengdan (圣诞) a generic term meaning “birth of a saint.”

Historically, shengdan could be celebrated as the birthdays of Chinese emperors (which was what Li Bai was referring to), various gods (as in a Daoist deity’s birthday ceremony described in the classic novel Dream of the Red Chamber), and Confucius, who is the “saint” whose birth the writer Lu Xun’s (鲁迅) is referring to in his essay “Shengdan Well-Wishes in Hong Kong (《述香港恭祝圣诞》)” in the late 1920s.

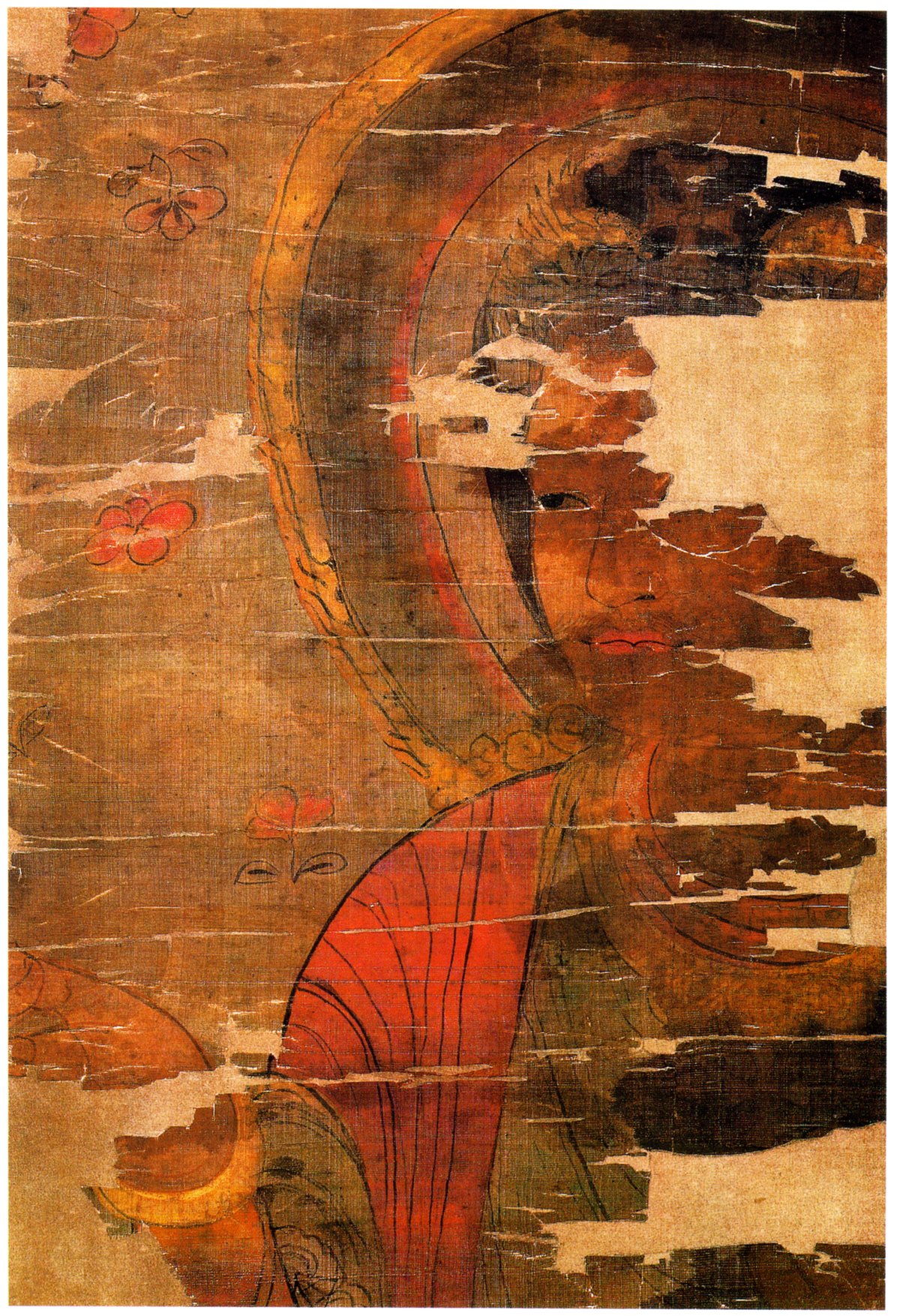

Yet despite this, Christmas has a longer history in China than one might think: While Li Bai’s Shengdanjie was not celebrated on December 25, it was close to his lifetime, a cosmopolitan period of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), that celebrations of Christ’s birth were first recorded in China on the Nestorian Stele, a large stone monument unearthed in 1623 in the former Tang capital Chang’an (today’s Xi’an).

The Syrian missionary Alopen brought the Nestorian sect of Christianity into China in 635 and established a church in Chang’an, and the religion later expanded into other cities. The Stele, which was erected in 781 during the reign of Emperor Daizong, states that Daizong would give special gifts to the church on “Incarnation Day,” or Christmas: “Always, on the Incarnation day, [Daizong] bestowed celestial incense and ordered the performance of a service of merit; he distributed of the imperial viands in order to shed glory on the Illustrious Congregation.”

The Nestorians, along with other religious groups, went underground by the mid-800s, as the Tang court became wary of the influence of churches and temples. Christians came to the Chinese court again in the 16th century with Jesuit priests, who worked as painters, astronomers, and scientists under the emperors of the Ming (1368 – 1644) and Qing (1616 – 1911) dynasties. However, the next notable Qing experience with Christmas didn’t happen until 1868, when Zhang Deyi (张德彝), a 21-year-old government official on a diplomatic mission to Great Britain, recorded a Victorian Christmas celebration in his diaries, along with many other cultural practices (like pajamas, punctuation, and birth control) that provide a fascinating look into the cultural differences of the time.

“On the day before Jesus’s birth, Catholic and Christian [Protestant] churches are lit up. The sound of music and chanting can be heard 10 li into the night. All the shops are closed, and men and women roam the streets at night wearing new clothes. Families with children will buy a small fir tree and hang various toys, paper dolls, packages, and candles on it,” wrote Zhang. During Christmas, “every family eats beef and plum pies...every church, home, and shop will hang a wreath on the door.”

In the following decades, many other government officials on diplomatic missions described Christmases abroad. One, Liu Xihong (刘锡鸿), mentions an “old man” who gave out gifts during a celebration in Germany. In 1877, Zhang Yinhuan (张荫桓), the Qing envoy to the United States, described a “peddler” dressed in green who gave out gifts to children at a Christmas party. He transliterated this benevolent figure’s name as “山特呵罗士 (Shāntè Kēluóshì ).”

In China during this period, foreign communities established with the arrival of missionaries and opening of treaty ports also celebrated Christmas, which took place around the same time as the traditional Chinese festival of Dongzhi (冬至), or Winter Solstice. Shao Zhize, a Zhejiang University professor of communications who published a book on the history of Christmas in China in 2020, wrote that Shanghai’s Shen Bao newspaper first referred to Christmas as the “birth of Christ” in an article on December 24, 1872, and would in later years try to explain the holiday to readers by giving it names like “Western Winter Festival” and “Western Solstice.” In the 1920s, it settled on the term “Shengdanjie.” Shen Bao also described a typical “Western family’s” Christmas celebrations one year, which included sparkling decorations and parties attended by many guests.

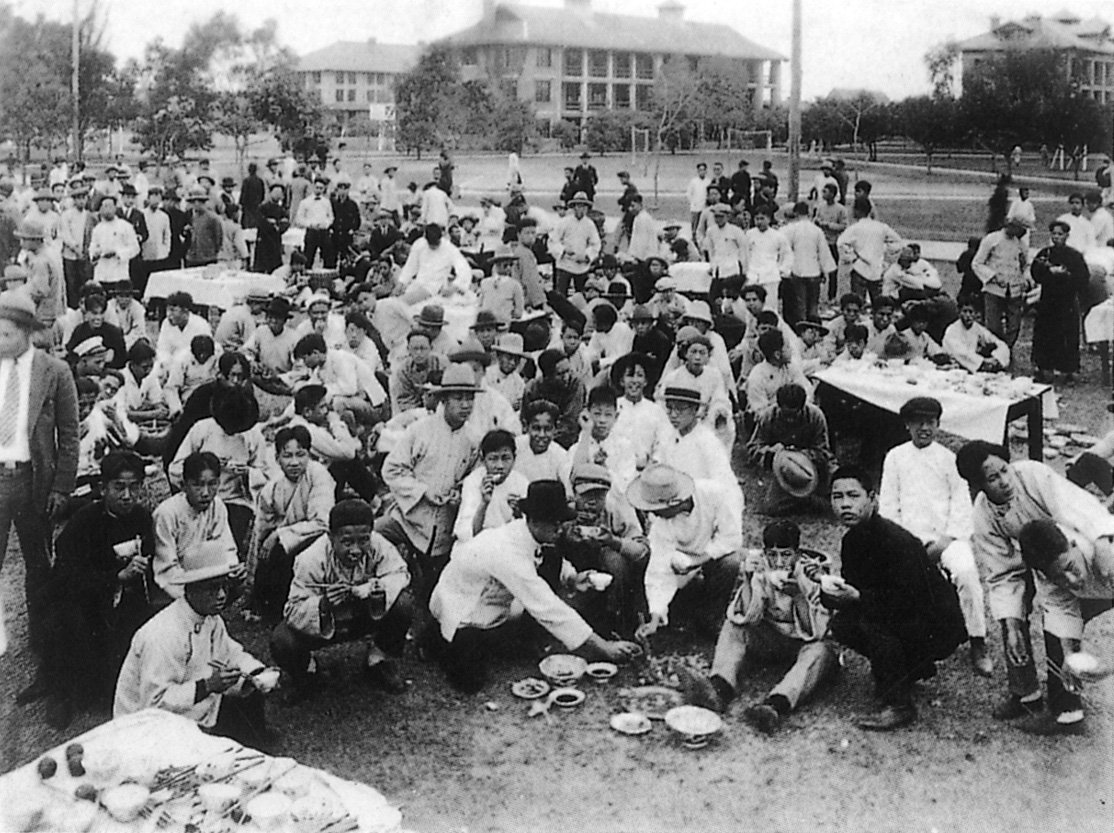

According to Shao, there were also large Christmas celebrations taking place in expatriate communities in Ningbo in the eastern Zhejiang province and Yingkou, Liaoning province, in the Northeast, from the late 19th to the early 20th century. By the early 1900s, Christmas had seeped out of the foreign concessions and become a public celebration in Shanghai, with Christian churches and the YMCA hosting concerts, pageants, and revelry for students and youths around the city.

The Eastern Sketch, an English magazine in Shanghai, published a Christmas issue in 1905 showing Father Christmas and a Chinese dragon strolling hand-in-hand along the Bund. Shanghai’s YMCA saw 700 people attending a Christmas concert on December 23, 1917. In Changsha, Hunan province, workers at the customs office got Christmas Day off in 1929; and from Guangzhou, there are photos of Christmas dances, as well as a Christmas picnic taking place at Lingnan University in 1925.

Christmas celebrations also drew some opposition during this time. As part of anti-Christian campaigns following the patriotic May 30th Movement in 1925, students handed out alternative greeting cards and pamphlets calling for boycotts of Christmas in December that year (which, Shao concludes, is evidence that Christmas cards were already in vogue by then).

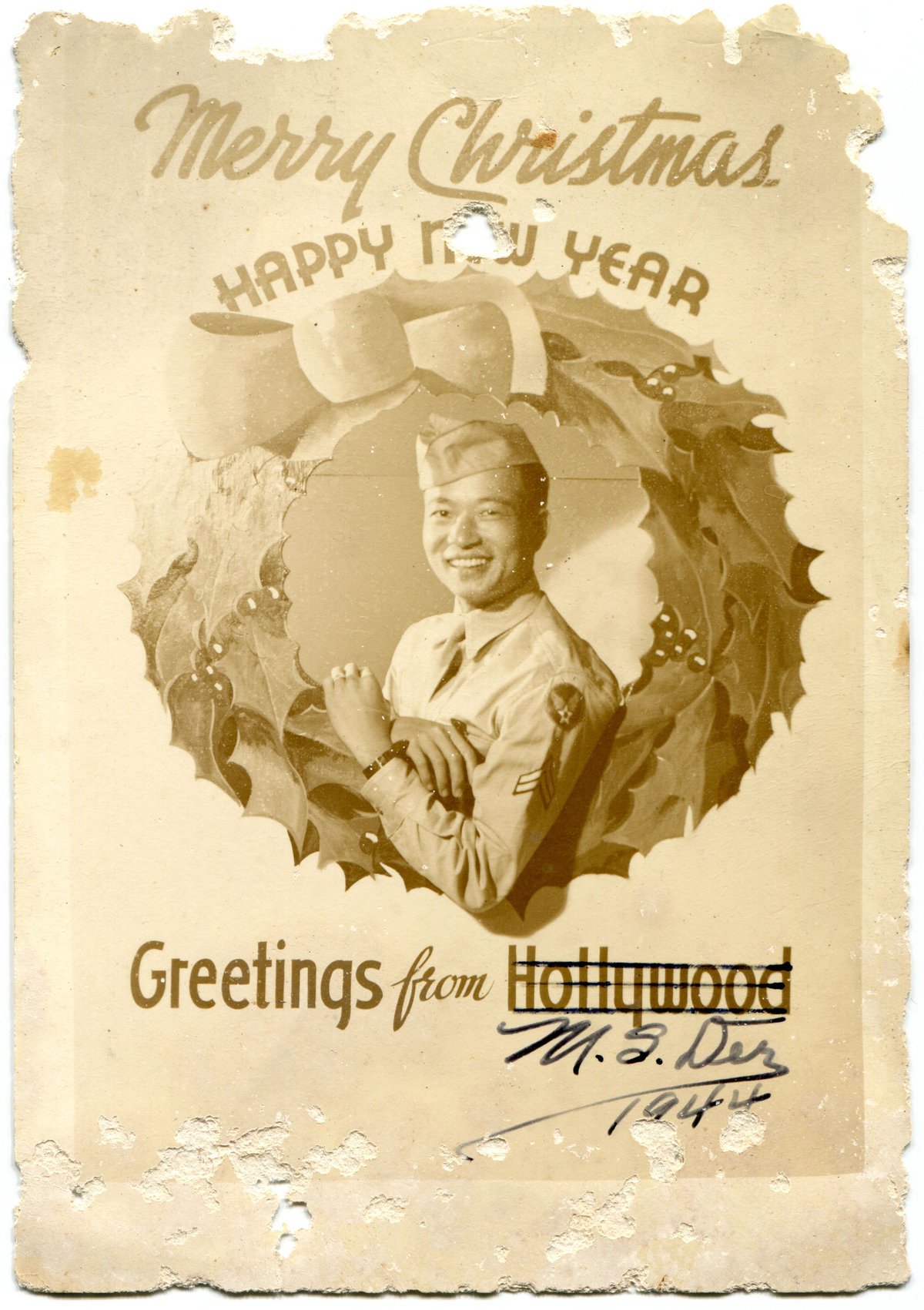

In spite of this, Shen Bao continued running Christmas ads, shop windows displayed seasonal goods, and restaurants and dance halls held holiday parties well into wartime in the 1930s and ’40s. But even Shen Bao couldn’t condone the merrymaking that took place in the midst of the Japanese occupation of Shanghai in 1943, lambasting in an editorial, “Last night was the birth of Christ, and a night of frenzied madness in all the pleasure places in Shanghai. In their revelry, people forgot what times we are living in.”

After the founding of the PRC, the holiday was still observed in a limited way at religious institutions. There are photos showing the Beijing YMCA holding Christmas banquets well into the 1950s. It would not return as a public celebration, though, until the Shanghai YMCA Hotel held a Christmas concert on December 23, 1980. According to a history blog called Gutong Yinghua, staff who worked at the event remember it as a low-key affair, with a bag of cake and pastries handed out to the guests in lieu of a feast. In 1992, the Shanghai Peace Hotel hosted the first edition of its Christmas dinner and fashion show, with tickets costing 888 yuan—about two months’ wages for a middle-class person at the time.

Today, Christmas decorations are ubiquitous in most major Chinese cities come December (and in fact, China produces around two-thirds of all the Christmas decorations in the world), while young people and businesses embrace the holiday as a season of romance. Well-known historian Tang Zhenchang (唐振常) once observed that Chinese people can more easily accept the material aspects of Western modernity than the ideological aspects, describing Shanghai’s adoption of Western cultural practices as “first surprise, then wonder, then envy, then adoption.”

In his book, Shao concludes that even if China on the whole rejects Christianity politically and culturally, it will still be able to embrace Christmas, as the holiday has become rooted in “common people’s consumption and enjoyment.”