What’s it like to have a learning difficulty in an education system focused on tests?

In China, about 5 to 8 percent of school-age children have dyslexia. In other words, one out of every 10 to 20 children may be dyslexic. But this large population is not widely recognized in Chinese society, to the point that many people haven’t even heard of the condition.

In China, dyslexia is sometimes also known as “literacy impairment.” It is a learning disability caused by minor differences in brain function. Typically, children with dyslexia have normal intelligence, but struggle with character recognition, writing, and reading comprehension. In their eyes, words can become an out-of-order, flickering, indistinguishable mass. They often mis-write characters or read slowly. When reading out loud, they may add or omit characters.

For children with dyslexia, words can seem like a pile of indecipherable symbols. The associated difficulties are often a source of strife for dyslexic people and their families.

-1-

The pain of reading

My name is Le Da and I’m 40 years old. My son is 10 years old, and in the third grade.

He started learning English at around age 3. After a year-and-a-half of study, I found that he had significant difficulty with reading and writing.

For example, take the English word “is”: Even though this is an easy word that occurs very frequently, my child had a hard time remembering it. No matter how many times I taught him, every time the word “is” came up, it was like a new word to him.

This surprised me, but at the time I thought it was just because he was too young. Maybe he would have an easier time when he got older.

But by his second semester of first grade, his teacher told me that he was reading and writing at far below his grade level. He couldn’t write as efficiently as his classmates, so it was harder for him to take notes in class. When reading, he couldn’t recognize enough characters for him to understand many of the assigned texts.

Later on, both the school’s feedback and hospital evaluations confirmed one thing for me: My son had dyslexia. When I knew for certain that he couldn’t read, I felt a sense of despair.

Because reading is a magical thing—it changes your vision of your future, something that’s even more important for children than adults. But my child can’t experience the wonder of reading. Whenever I think about this, a kind of grief wells up in me.

I felt that he must be very lonely, with no way of understanding the world beyond his own sensory experiences.

In truth, he understood that he couldn’t recognize enough words for someone his age, and would have to take time to build up his literacy. But this process was very painful to him.

One day, I quizzed him on all of the vocabulary from one of the first-grade textbooks. A third-grader should have no issue writing over 100 characters, but during this process he kept asking me, “Is there more? Why isn’t over yet?”

He couldn’t write most of the characters in the book, and the dictation was slow going. Every few words, I would have to encourage him to keep going.

When the quiz was over, I told him, “I’ve marked all of the words you don’t know how to write. Now you can take some time to read and write out these words on your own a few times. After that we can quiz you again.”

I left him alone for a while. An hour later, I came back to find that he had only written about a dozen words.

When it came to learning, he took an attitude of “nonviolent resistance.”

We’ve made many study plans to improve his performance. But whether I used incentives or took time off work to help him, we would always hit a wall eventually and have to abandon our plan.

Whenever the homework got stressful, or if he had too much fun or physical activity during the day, he would try to get out of studying in the evening. He’d often lie down on the table, acting like he was too sleepy to function.

If I told him to sit down and study at his desk the next morning, he would just stare blankly. In short, he would do whatever it took to waste time.

After seeing plan after plan come to nothing, I once told him, “When it comes to letting me down, you’ve never let me down.”

He didn’t react, just listened in silence. From his perspective, I might have been right about everything; he acknowledged he had all these problems, and knew what I hoped for him, but he couldn’t do it.

I often regret those harsh words, but whenever I see his resistance to learning, I feel extremely anxious.

-2-

“Dad, can you make me a presentation?”

One day when my son got back from school, he asked me if I could make him a PowerPoint presentation.

I was curious, and asked him why. He said the teacher had put them in study groups; each group had to choose a topic to present on.

It was only later that I discovered that the students were actually free to choose their own groups, and it was a student from this group that “took him in”—which is to say that none of the other groups wanted him.

Even though I made a regular effort to keep up with how my son was doing in school, it was only in that moment that I understood all that he was going through.

I had very complicated feelings about this—maybe something like guilt.

Later, I made an excellent PowerPoint and divided the presentation into sections. I hoped that my son and his classmates could each go up and deliver a section.

After the presentation, I learned that they had indeed done as I had imagined, each of them taking responsibility for a section; that is, all except for my son.

He took on a different role: clicking through the slides. He told me, “You made such a beautiful presentation that I wanted to be the one showing it.”

But I knew that it was actually because he couldn’t read the script. He didn’t want to embarrass himself in front of the whole class, so he used this as a way to protect himself.

Due to our society’s current lack of understanding and acceptance for dyslexia, dyslexic children and their families often feel isolated in their struggles.

As a child literacy evaluator, literacy coach, and social worker, Zhong Tan understands this well. She has been working in dyslexia awareness and intervention since 2012.

-3-

There’s more to learning than reading and writing

In 2014, for World Book Day in April, I set up a booth on a street corner to raise awareness about dyslexia. When I was passing out flyers, an old gentleman ended up debating me for over half an hour because he had always thought that this “dyslexia” business was nonsense.

As a teacher with decades of experience and government awards for distinction, he felt that there were no students who couldn’t learn, only teachers who couldn’t teach. If a student wasn’t doing well, there was either an issue with the student’s attitude or the teacher’s ability. Therefore, dyslexia couldn’t possibly exist.

This man made a deep impression on me. He also wasn’t the only person I met who doubted the existence of dyslexia.

These people are challenges I’ve encountered in the course of my awareness work, and they are also why I wanted to raise awareness in the first place.

Because whether it was children or adults, all of the dyslexic people I met over the years faced the same predicament: When nobody understands dyslexia, they are constantly stigmatized. They were labeled as “stupid,” “lazy,” or “having a bad attitude,” labels that make sweeping generalizations about a person.

But when a person has dyslexia, then it’s a very concrete challenge—they simply have difficulty with the written language. And if we deepen our understanding of the condition, we would see that this is not an insurmountable difficulty.

Many dyslexic children give up on learning because they think that “learning” means reading and writing. But in reality, there’s much more to learning; they can learn by watching videos, listening to stories, and so on. We frequently put too much emphasis on having our children acquire knowledge through written words, so we need to let parents and other adults know that words are not the only way.

-4-

Multisensory training

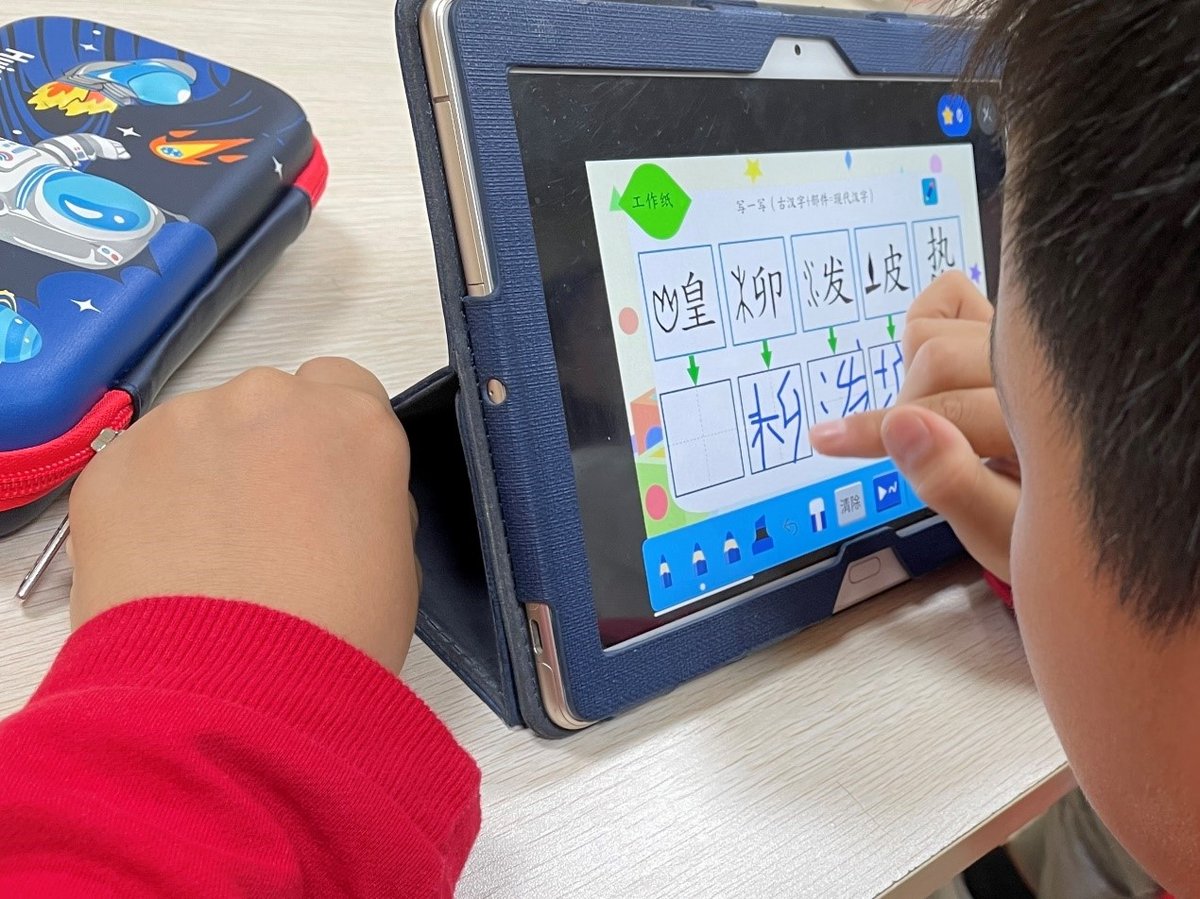

People have multiple senses for taking in different kinds of information. We use more than one sense when we’re memorizing a character.

For example, most people have children memorize characters using their eyes alone. But when my colleagues coach children, we also have them feel the shape of the characters and listen to how they are pronounced.

I once met a third-grader who still didn’t know 树, the character for tree. One day, his mother took him to the park to be with the trees: to touch them, feel them, and hug them. After receiving this multisensory stimulation, he was able to remember the character. He later used similar methods to remember 湖 (lake) and other characters.

Dyslexic children need to see, hear, touch, and feel the characters in order to remember them. Experiencing positive emotion in the course of this process also helps their memory.

As a result, we generally encourage parents to let their kids learn in a more pleasant emotional environment. Otherwise, they’d have to spend more of their energy on managing their stress and anxiety, rather than learning.

Multisensory training, reading together, and reading games are some of the methods currently used in dyslexia intervention. In addition to tutoring children with dyslexia, Zhong also comes into contact with dyslexic adults in the course of her work—among them, Tu Dou.

Tu Dou is dyslexic in English, but didn’t receive her official diagnosis until adulthood.

In spite of her dyslexia, Tu Dou majored in English linguistics. She even went on to become an English teacher after graduating.

-5-

Characters are just images

I realized very early on that I was different from others.

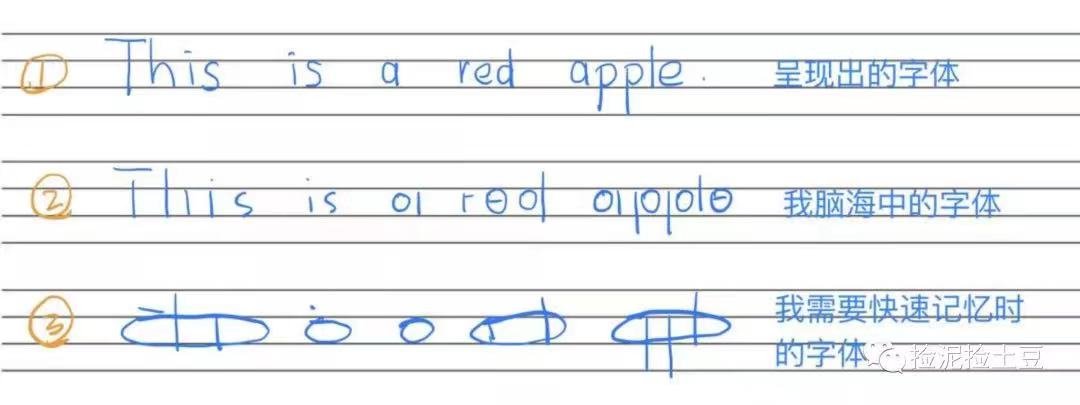

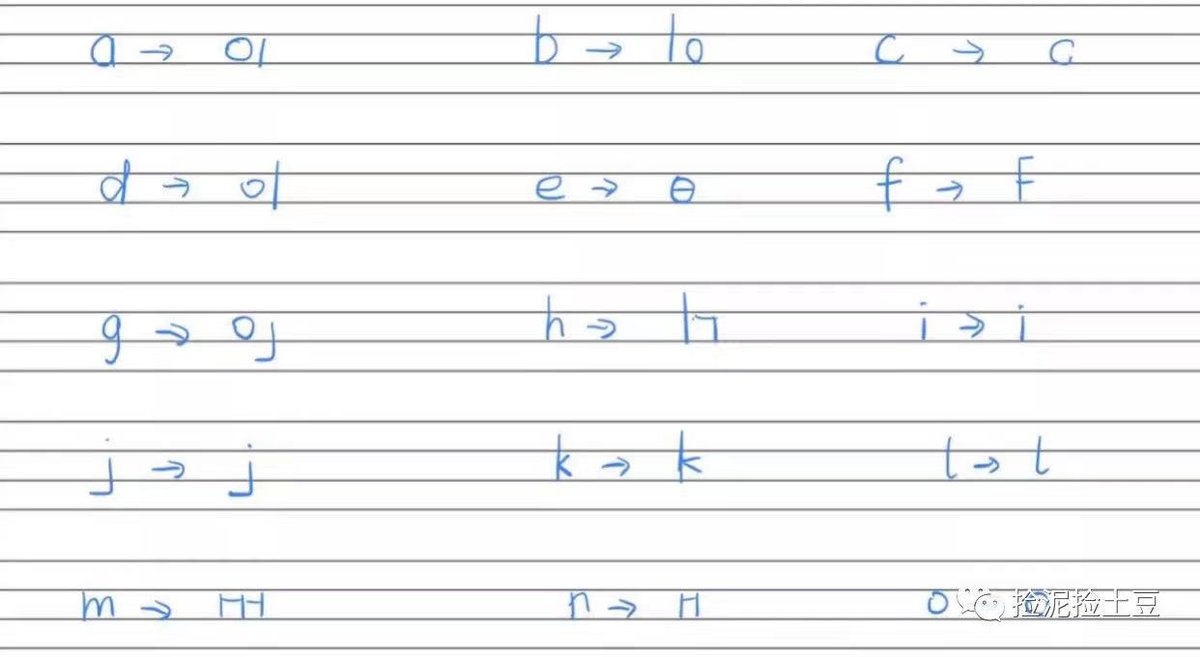

When we had to memorize English words in the first and second grade, I found that I had trouble remembering them. To my eyes, the words were images, but I had no clue what these images meant or how they should be read. I had trouble even passing my tests.

Later on, I started to panic. Around fourth or fifth grade, I asked my mom to help me find a remedial class. She didn’t sign me up for just any class; she took me to sit in on all kinds of classes to see what the content was like, whether I liked the teacher’s methods, and so on. My mom wanted to make sure that the teacher was a good fit for me—that was the only way she would feel comfortable sending me.

So I actually found an excellent teacher to introduce me to English. From fourth or fifth grade until the end of elementary school, we were constantly reinforcing my knowledge of phonetics. Even though I had dyslexia, I was quite successful in learning English phonetics, thanks to the great foundations this teacher laid for me.

Currently, some researchers believe that rather than viewing dyslexia as a disease, it is better to see it as a unique way of receiving and processing information. Although people with dyslexia can’t convert between sound, form, and meaning as easily as most others, there are those, like Tu Dou, who have still been able to work with their so-called “defects” and develop their own learning methods.

-6-

Memorizing through drawing

Studying was still fairly difficult for me in junior high, but I would force myself to learn. All I knew was that I needed to work hard. Even though I didn’t know when I would see improvements, I felt that if I didn’t try, I might never improve.

The turning point came during a morning reading session. At the time I was leaning over the table, using a pen to copy the words from my textbook into my notebook, like I was drawing.

For example, I could break down the word dog like this: The letter d was like a circle with a stick next to it, the letter o was like a little circle, and the g was like a circle with a hook.

For me, the word dog was more like three independent circles, each with some corresponding marks in its vicinity.

So rather than memorizing words, I was actually memorizing a puzzle. Over time, I found that using images and visual stimuli as memory aids was a huge help for my learning.

-7-

The power of language

Although I struggled with reading and writing, I gradually discovered that I had a knack for speech in English. To some degree, my verbal training also helped me understand the textual world.

When I was in junior high, my mom found that I enjoyed the spoken word, so she would encourage me to enter speech contests and debate tournaments. The deepest impact these activities had on me wasn’t the awards or rankings I received, but rather the process of writing and continually revising my drafts. This was the most enjoyable part for me.

One speech in particular left its mark on me. At the time, in addition to a scripted speech, there was an open portion of the competition where contestants were asked to give a presentation. I chose to present an iconic scene from my favorite film, Jane Eyre. In order to interpret this scene, I needed to play two roles, immerse myself in a theatrical setting, and use English to process and perform the dialogue.

In that moment, I discovered that I suddenly had an understanding of English literature.

That was the first time I truly felt the power of this system that was once so foreign to me. As someone who always struggled with reading, this brought me to a whole new level of delight. I was no longer simply memorizing words by rote, but instead putting myself into a vivid scene and feeling the power of language for myself.

-8-

Transcending language

In junior high, I liked speech, theater, and hands-on learning. I also developed many hobbies outside of my studies, which improved my confidence and made me less anxious about my schoolwork.

But high school came with a dramatic increase in pressure. The school restricted students from engaging in hobbies outside of studying, so I got caught up in an evaluation system with only one metric.

Because I was under so much pressure, and no amount of studying improved my grades, I felt very anxious and helpless. I had severe panic attacks during my third year of high school. Before every test, I had to go to a quiet place to calm down. Otherwise, I might start hyperventilating.

I have had several panic attacks that led to temporary limb-paralysis. If I didn’t do controlled breathing at that point, my body might become fully rigid—a dangerous condition.

I originally lived on the high school campus, but I went home to recuperate for a while because I was in bad shape.

When I was at home, my mom and I actually didn’t talk much, but she did study with me during my hardest time.

Every morning at 6, we would get up together, and then we’d each study our own materials. When we hit a tough part we’d encourage each other. During that year, my mother earned the titles of senior economist and senior accountant, and I got into university.

I feel that action is much more powerful than words. Later on, whenever I ran into trouble, I would put my head down and work through it. This kind of persistence was her influence on me.

-9-

Getting recognized

When I was doing postgraduate studies abroad, I found out that the university could provide dyslexia assessment and support, so I went to have my diagnosis confirmed.

The university’s Office of Student Support gave me a preliminary screening before referring me to a partner institution for further evaluation. We did some cognitive tests and language ability tests. At the end of each test, they would sum up the indicators based on my performance.

One component of the evaluation was taking dictation of words. These were not real words with specific meanings, but rather very odd phonetic combinations. The goal of this test was to see if I was able to match the form of the words with their sounds. I really wanted to write something down, but I simply couldn’t. The doctor took detailed notes during this process.

A couple weeks after the evaluation, I received a formal diagnosis of dyslexia. The doctor gave me a paper report that included my reason for evaluation, as well as the final analysis of my scores. The institution also gave my university a copy of the report and some recommendations, which would be used to make suitable accommodations for my studies.

For example, whenever I took a test, the university would give me 25 percent more time than other students, and my professors would also receive an email from the university informing them of my situation. Also, because I would still be taking the test as other students were packing their bags and leaving, my professors would seat me in a corner to minimize distractions for me.

Those measures proved very helpful to me. Previously, even if I studied hard, my grades were average at best, because I often couldn’t finish the exams. But after I received extensions on my tests, I was able to achieve very good grades, because I had time to process the information, and to think about what I had memorized and learned in class. This was all quite necessary.

Because many dyslexics also have difficulty with language production, and need more time to write essays, the university would also give me accommodations for writing papers. For example, professors would extend my essay deadlines by a few days, which gave me more time to write and revise.

During that period, I realized that I didn’t need to be ashamed of my differences. In an inclusive and diverse educational system, dyslexics can be recognized, can enjoy their education without interference, and can compete on more equal footing.

When I was studying linguistics, I once came across this sentence in my readings. The gist of it was that there is no instinct for reading or writing—written language has no fundamental existence in our world. Ultimately, words are only a medium. With enough support and assistive technology, such as speech-to-text software, dyslexics can go to school, take exams, and work just like anyone else.

Having struggled so much in school, Tu Dou might never have imagined that she would one day become a teacher.

And though dyslexia will never leave his son, and the future still seems uncertain to Le Da, he still has hope.

-10-

“How did Da Vinci do on his exams?”

About a year-and-a-half ago, I was in a slump due to a challenging period at work.

One day, my son asked if I could go out and play with him for a bit. Even though I didn’t really feel like playing, I decided to take a walk with him. Or maybe it was more that he was taking me for a walk.

The two of us wandered around aimlessly. My son saw that I wasn’t in a great mood, and asked me what was wrong. I said that I was feeling lots of fear—about aging, about work, about an uncertain future.

Hearing this, my son was at a loss. He had no way of understanding the meaning of these fears. So I said to him, “I feel like I’m already so old, and haven’t really accomplished anything. I’m scared that I’ll muddle my way through the rest of my life and be looked down on by others.”

My son was silent for a while. Then he asked me a question.

“Dad, I really like to draw. Do I need to take any drawing exams?”

I opened my mouth without thinking: “Yes, you do.”

Then my son asked again, “Dad, how did Da Vinci do on his exams?”

I felt a light bulb going off over my head. I thought: That’s right, no great painter ever achieved anything by doing well on tests; they got there by bucking the norm. Then I turned to look at the boy next to me. It’s true that he struggles in school, and faces many challenges, but he also has many talents.

He was strong enough not to be discouraged by my harsh words and bad temper; he was kind enough to put play time aside to be with me when he saw that I was feeling down.

I think these are crucial traits. I believe that these special traits can help him forge a meaningful journey through the rest of his life.