In this short story, writer Gu Xiang finds humanity and humor in the idiosyncrasies of elderly Chinese

On the morning of June 23, 2016, Gu Cunxing rises from bed at 4:30 a.m. Cooking over firewood, he prepares some corn porridge for himself and his wife, Shen Haiying. Gu pours a spoonful of white sugar into the bottom of his bowl, waits for it to infuse slowly into the porridge, and eats it at a snail’s pace. Shen takes hers with pickled cucumber. She stands up as Gu makes to leave the house.

At 5:34 a.m. Gu cycles the four kilometers from his village to Shenjiang Road subway station. “Bleep! Senior card!” chimes the entrance gate. As if explaining to everyone in earshot: Please scrutinize this person. Are they old or not? Yet nobody is around, and there is no sign of the security staff. Gu takes the first train westward.

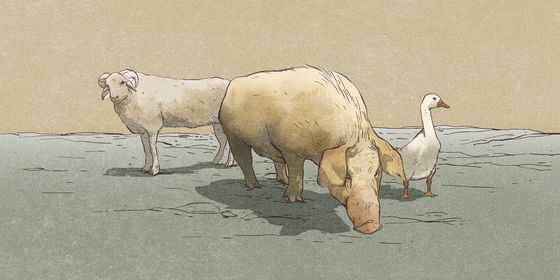

Gu’s zodiac animal is the Sheep. By the year’s end, he’ll have reached the ripe age of 73. He looks every part the wizened old man. Unlike some men of his age who dye their hair, he has his shock of white trimmed smartly at a barbershop that offers free haircuts every Wednesday for customers over 70. Gu cuts a slender figure in his freshly laundered shirt. Deep grooves emerge from his sunken cheeks to sketch a jocular expression. His smile has a few gaps for missing teeth. He has large, bright, thin-lidded eyes and a ruddy complexion, suggesting some breed of handsome monkey.

Gu doesn’t own a mobile phone or read books, and is content to watch the succession of people as they fill the train carriage. He rides for two hours, changing trains twice, until he reaches Huaqiao station. From east to west, the route spans approximately 55 kilometers.

Outside Huaqiao station, the bus stand displays two routes into the surrounding villages. The queue for the Route 151 bus to Kunshan stretches the length of the railing, while the Route 7, which came by just five minutes ago, has fewer people. Gu feels the 151 will arrive sooner, so he joins the back of the line. The queue consists of elderly people decked out in sneakers, backpacks, and hats, heading out for a day of recreation. The women all sport sunglasses; the ones traveling with men tend to be quieter, but the women traveling in groups seem astonishingly at ease, chattering away merrily in a way that hints they may repress something in the presence of men.

The seniors wait happily, with nary a care and lots of energy to spare. Somewhat surprisingly, it feels as if they have never experienced a desperate moment’s worry in their lives. Perhaps the people whose cares weigh heavy on their heart all shuffle off well before getting old. Or perhaps, if they’re lucky enough to last the distance, they loosen up at their own good fortune, entering the ranks of the joyous and content.

After a short while, the 151 bus arrives. Gu joins the throng of boarding passengers. His Shanghai senior card is no use to him here, but he can swipe his public transport card, which nets him a 40 percent discount. This is a journey he has taken before. With nowhere left to sit, he leans against the driver’s cab. Gu glances at his wristwatch and fishes out a hardbound notebook to jot something down. Then he notices an elderly man standing opposite him. He has seen the man at least three times before, most recently on this same bus the day before yesterday. As he is thinking about this coincidence, the man looks over, and the two exchange a smile that seems to say, “Fancy seeing you again,” and “Yes, what a coincidence, wouldn’t you say?”

The man asks, “Where are you headed?”

“Nowhere in particular,” Gu tells him. “I’m just going out for some fun. Wherever I end up—that’s where I’ll go.”

“Have you been to Luxiang Ancient Village?”

“No.”

“Then how about coming along with me? I’ll take you,” the man offers.

“Sounds good,” muses Gu. “Well, isn’t this good timing?”

“It certainly is. You on your own?”

“I like to go around on my own—it’s convenient.”

“Fair point, but traveling together has its merits too, no?”

“Two days ago I went to Tiger Mound with two other guys,” says Gu. “We saw the famous inscription by the poet Su Dongpo: ‘To visit Suzhou and miss Tiger Mound is something to be sorely regretted.’”

“Your friends?”

“Nah. Nobody I knew, just people I bumped into along the way. I met them in Luzhi.”

“To Suzhou from Luzhi! That’s quite a long way!” The man sounds impressed.

“I wasn’t really thinking about it. I met some people who mentioned they were off to Suzhou, so I went. Anyway, I’ve also explored the area around Luzhi.”

“Let’s set our sights on Dongshan today; it’s quite a way off,” the man suggests.

“Suits me. In any case, I haven’t been before.”

“There’s an ancient village out that way.”

“Have you been?” asks Gu. The man says that he has.

“Was it any fun?”

The man smiles, explaining: “Old towns and cities—they’re all more or less alike. Both fun and no fun, at the same time.”

At this Gu laughs. “They are all pretty much like that. I’ve also been to my share of ancient villages—Zhouzhuang, Tongli, Qiandeng, Mianxi…”

“So, when you say you went out for fun, you just mean you visited an ancient village,” the man jokes.

“You’re not wrong,” concedes Gu. Their moods are in no way dampened by the fact that ancient villages are no fun.

“I like to go off on day trips,” Gu remarks after a pause. The man asks whether he always goes solo. Not always, Gu says, explaining that he has traveled with others—people from his own village, for instance. “There are two guys that joined the military long after me. I enlisted in ’63; they did it in 1970. They’d be covered in sweat by the time we were halfway up the mountain, and I’d be as energetic as ever. After that, they stopped inviting me along, saying I was too old.”

Elderly day-trippers collect and pass around all sorts of information in places seldom visited by younger tourists. For instance, you can get group tours for 98 yuan that offer 2.5 kilograms of complimentary kiwifruit, or spend two nights, three days in the city of Zhangjiagang with a complimentary bus to Haining Leather Market for just 200 yuan. Flyers printed on pink A5 paper blare: “Experience a day of golden years leisure on Chongming Island! Recruiting ‘golden age’ volunteers between ages 45 and 70. Must be healthy and responsible. Contribute the remaining energies of your twilight years. Volunteers enjoy discounts on all charges.”

Why would a 45-year-old want to be lumped into the same age bracket as a 70-year-old? What age bracket are you in if you are above 70? Those who just turned 45 become ripe targets to be scammed out of their savings by these tour operators, who look at you with a mixture of contempt and pity if you’re between 45 and 70 and a pauper, as though they won’t be just as poor when they hit 45. Yet if somebody had the money, why would they join a cut-price group tour? Well, perhaps if they are naturally frugal and averse to spending. Maybe they want to be part of the bustle of a group and be led by a guide, and by the end of it, owing to their pure heart, feel moved to part with some of their savings on the products sold on these tours.

Not so for Gu, Shen, or their elderly acquaintances, who didn’t play into the scammers’ hands. “I don’t buy anything they try to sell me,” says Gu. “Some people buy from them. Out of a group of 40, six or seven might blow 4,980 yuan on the products, believing they could treat this or that illness. With health as good as mine, I don’t need it.” He doesn’t go for their sales pitches, but it doesn’t bother him. Going to see Haining Leather Market is traveling all the same. The people who run these schemes have run the numbers. In simple terms, people above 70 just aren’t profitable. “My health is great. I’ve never had a complaint. I haven’t even taken medicine. I haven’t been to the hospital,” says Gu, still unconvinced.

His health really is as good as he says. He’s always outside, pottering about his yard or his private plot. He likes to occupy himself by raising crops, keeping things tidy, setting up or tearing down a trestle for growing melons, mending fences, and sawing tree branches. He does a little over here and a little over there. He has built a system of dikes beside the small creek nearby. Anybody who sees them clicks their tongue in admiration, saying what an impressive undertaking it is. In the narrow winding paths that run between the rows of his vegetable patch, there has sprouted an exquisite patterned carpet of flowers, the likes of which people have never seen. He covers the bamboo stakes with wide-mouthed bottles to keep the rain out and slow down their rotting.

In the winter, Gu uses a foam board to block out the wind on the northeast side of his yard, which was well-lit but breezy, so that he and Shen can sunbathe. The carpet of flowers which spread throughout the field ends with a rectangular ring of stones by a small pond. The little paths are paved in marble, and at the front gate stands an enormous porcelain flower vase. Everything Gu has used—asbestos sheets, waterproofing materials, aluminum insulation sheets, a hula hoop—were all scavenged over the years as the surrounding villages and factories were demolished and relocated. Some things were so large that it’s a wonder that he managed to get them home on his own. “Carried them on my bike,” he says. “When people saw me, they’d all cry, ‘Good heavens!’”

The cupboards, tables, chairs, and bedframes are all made of wood. Wood is handy; there’s no end to its uses. Although everything in it was scavenged, his small yard remains the prettiest in the village. Different plants take turns to sprout through the year, growing in joyous profusion. All types of flowers bloom constantly alongside his crops. At the field’s outer edge, the glossy hedge is pruned into the shape of a three-tiered pagoda. Now, however, it seems nobody appreciates this. The neighbors prefer to cover their land with crudely made houses and rent them to outsiders.

Gu started farming the land after retiring from his job at a state-run factory. He was born in Shanghai and served as a solider for six years. He was a crack shot and a decorated grenadier, but he didn’t have the right class background—his family were petty landowners, who rented out seven mu of land.

Gu’s career didn’t advance in the army, and he was eventually discharged, whereupon he joined the factory. There, he operated a machine, producing valves for other large factories in Shanghai. He did this for many years, and by the end, he didn’t qualify as a worker or a farmer. His pension amounted to less than an average person’s welfare payments in a small town. He was left with about 2,000 yuan. Neither he or Shen wanted to build houses on their land. When Gu ate vegetables, he only took the tender leaves near the top. He doesn’t keep food overnight. He and Shen didn’t use the fridge. At the supermarket, he’d catch sight of the “outrageously expensive” vegetables and lament that “all of the old ones have to be thrown away.”

Gu and Shen’s cat frolics freely in their vegetable patch, trampling the plants and digging up the soil. When Shen moves to chase it away, Gu says: “Let it play. We have so many vegetables growing, so what’s the harm?” He can also twirl a hula hoop round and round without stopping; chalk it up to the years of daily manual labor that left him skinny and flexible.

People ought to call him “Gu the Hardworking” or “Gu the Capable.” He is a different breed from those who sit around all day doing nothing. On the 21st of the previous month, he’d written down a sentence in his small notebook: “Dredge the silt on the riverbed. They said they’re going to develop the land. I’m still dredging.” On the 22nd, he wrote again: “Dredge the silt.”

Back on the bus his new friend asks, “Where do you live?”

“Pudongcao Road,” Gu answers.

“I’m over in Jiangwan, out by Wujiao Square,” the man says. Gu tells him he attended a two-month tractor driving course near Jiangwan when he was 19. The man also asks if Gu has any children, adding that his own daughter went to Japan after college to work in the animation industry. Gu finds this all rather impressive. “Been to Japan yourself?” he asks.

“No, getting there is an awful load of hassle,” the man says.

“Oh,” says Gu. He says he does have a son, who was 43 years old and still unmarried. His son doesn’t live with him and Shen, but Gu went over once every other week to take him some food. “My daughter hasn’t married either,” says the man, but he doesn’t seem all that sure of the fact.

You can count on your children less than you can count on a sports match. Gu enjoys flipping between sports competitions on the TV. Every week he goes through the newspaper listings and circles the matches he wants to watch, like people used to do 20 years ago. He even watches the midnight games. He watches table tennis, badminton, volleyball, and swimming, so long as there’s a Chinese team that might win. Naturally, that means he doesn’t bother with soccer, so the ongoing Euro 2016 Tournament has no impact on his sleep.

He tells his companion about meeting the badminton world champion in Kunshan last month, where she was selling memorabilia and signing autographs. He’d also heard that Chang Hao, the vice-chair of the Chinese Weiqi Association, came to Tongli to play Go the previous month. Following sports makes him feel a little more connected to those places.

The man on the bus doesn’t watch sports much. Generally, he’s more interested in catching a 40-minute bus to Lu Xun Park to listen to people shooting the breeze. “It’s different,” he says. “There are a lot of people in Lu Xun Park. Plenty of folks to listen to. I need to brush up on my skills. There’s a pair of folks that discusses current affairs—they’re on top of things. But we’re a small group, so we go back and forth but never see any improvement.

“If you get the chance, you ought to visit Lu Xun Park yourself,” the man continues. “There are 50 times the number of old people there compared with regular parks. Folks singing, dancing, bragging, exercising—people doing every imaginable thing. It’s as busy as a nightclub, one that opens in the early hours. There’s this old woman who sits among the pack of old men throughout the day, making a special effort to squeeze up against their bodies...talk about comedy! We’re all there to listen to the debates. Who’d pay any attention to such a stupid and strange old woman? Nobody pays her any mind.”

The 151 to Kunshan takes approximately an hour to get to its last stop, Nangangqi. All of the remaining passengers disembark. Gu and his companion’s next bus is right behind them, and they ride it for six stops before transferring twice more, taking about half an hour on each route. “Normally we’d already be in Suzhou by now,” Gu thinks.

“There’s a longer stretch coming up. Did you eat enough breakfast?” the man asks.

“I’m full. I also have some snacks on hand,” Gu replies as Route 62 comes.

There aren’t any seats as they get on, but some space frees up after two stops. As they sit, the man says, “My stomach is growling.” He roots around in his bag for some pastries and peanut nougat. Gu searches his own stash and pulls out a peach pastry and a cucumber he picked from his own garden that morning. The cucumber is fresh and tender, with burrs intact, perfect for sharing. After he is done eating, his companion nods off. Gu regards the man’s hair, dyed an unnatural pitch black.

Route 62 is extraordinarily long. In total, they make 55 stops over an hour and a half. You could play out a whole volleyball match in that time, with a final score of 3 to 1. There is nothing much to hold Gu’s interest along the side of the road.

The man who insisted on dragging him out to Dongshan has abandoned him for the land of dreams. Suddenly, Gu feels uneasy. “Where are we getting off, exactly?” he thinks. “Won’t we miss our stop?” He stands up and makes his way to the front to check the route map. Sure enough, there among the final few stops, the characters for “Dongshan” pop out. He returns to his seat. If his companion isn’t going to wake up, then it would be best to ride through to the end, he thinks.

Very little is happening—no movement, no sound; much the same as when he took the subway as a military officer in years gone by. When his fellow soldiers received their rations of four bags of rice and four tubs of oil, and he only received two of each, he’d said nothing and had borne no complaint in his heart. He was similarly unfazed when jealous neighbors trampled his flourishing vegetables. They would grow right back in a couple of days. Perhaps a better nickname for him would be “Gu the Even-Tempered.” He isn’t at all like those people who burn with impatience.

Gu doesn’t get motion sickness anymore. Two years ago, Shen fell down the stairs on her way to the toilet at 4 a.m., breaking her arm and causing badly swollen legs. Gu brought her the 14 kilometers to Chuansha People’s Hospital on his bike. The next day, he got motion sickness on the bus ride back to the hospital. But knowing the alternative was a two-and-a-half-hour round-trip daily bike ride, he kept taking the bus until he got used to it.

The man traveling with Gu wakes up just as they are about to reach the station. Gu is a little taken aback, but the man is matter-of-fact about having the ability to never sleep through his stop. He always wakes up as he arrives at the station, no matter how unfamiliar the route is. This is a skill possessed only by those who have spent countless years as passengers on public transport.

As it happens, the two men don’t ride to the end of the line. Instead, they disembark at Qiaotou and wait for the No. 627. “There’s one final bus, but it’s quick. After that we won’t have much further to go,” Gu’s companion says, as if afraid that Gu is ready to turn tail and head home.

This place certainly looks pretty rural. A woman carrying a bundle on a shoulder pole places it down to wait at the bus stop. Next come two people hauling farm tools. It’s a scene right out of the villages in Pudong, just like the people of Gu’s home village waiting for the shuttle bus. They come into town to buy seeds, fertilizer, or a pair of shoes. Now they’ll take this bus back home. Just as the bus pulls up, another knot of old folks wanders over. You can tell they’re not far from home, that they’re wise to their whereabouts. They’ll be just fine, even if they’ve got nothing with them.

Seniors crowd the inside of the bus, and more get on at the next two stops. The bus is now teeming with old people, all of whom seem excitable and familiar with each other—exchanging greetings, chattering in dialects Gu can’t completely make out. Gu’s mood lifts as he gets caught up in it. Just as kids marvel at seeing so many others, so do the elderly savor meeting so many other people of the same age, as if they have all gathered to celebrate their own longevity. The young and middle-aged don’t display similar zeal when they meet others of their kind. How depressing it would be to consider the number of other middle-aged people in the world!

The elderly passengers board the bus at Dongshan People’s Station West or Dongshan Post Office. They go see the doctor, get their medicines, or draw their pensions. Later, they peel off at stops with names like “Health Village,” “Princely River,” “Starlight Village,” or “Golden Tower River.”

All of them look fit and able-bodied, not as though they have any pressing health concerns. Gu is happy for them, feeling as if he has reminisced about the old days with them despite not having spoken a word to them.

There are several villages in these parts, and Lake Tai too, so public buses serve the area. No buses go to Gu’s home village. Everywhere else has urbanized, leaving one little village and its small population of stragglers. Nobody spares a thought about how they should get around. This year, even the shuttle bus was canceled. Two years ago, the bridge in the north was demolished and the riverside road was cut off. When the highway to the south was re-laid, Shen naïvely held out hope for a public bus. But in the end, everyone still had to travel under their own steam, by either car or bike. Shen doesn’t use either. Once, she had Gu take her on the scooter to buy some adjustable straps, incurring a 30 yuan fine for illegally transporting a passenger. As a result, she is even more reluctant to go out. Day and night, year in and year out, she deals with her affairs within the village’s closed circle.

Outside the bus window, a cool wind blows. There are mountains and lakes in all directions, as well as orchards, tea plantations, egrets, water shield plants, the month of June and the drizzling rain. Gu is reluctant to disembark when his companion calls him to come explore the Zijin Nunnery. At the entrance, there are people selling bayberries—the last of the summer. The man asks Gu if he’d like to buy some, but Gu declines—bayberries are too sour for his tastes. The man then motions for Gu to go on ahead, saying he has visited before and will wait outside. He looks as though he was yearning for some bayberries.

Gu enters alone, noticing the painted sculpture of a famous arhat inside the small temple. It didn’t look like much. “Out of all the old fogeys in the world,” he thinks, “somehow this one managed to become an arhat.” He ponders this further. The Buddha himself was a person to begin with; perhaps so too was this arhat. He sees another statue of a beaming arhat whose eyes are fixed on a small, yellow, round-headed cat resting by its knee. He leans in closer to scrutinize the placard, which reads: “Tiger-Subduing Arhat.”

“This tiger is too small,” he thinks. “Perhaps the arhat fed this cat all his life. He was good to cats.”

But the ancient trees at the Zijin Nunnery deeply impress him. “Amazing!” he gasps. Gu lifts his head to take in a 1,000-year-old gingko, only the second tree of such an age he has seen, the other being a breathtaking magnolia in Kunshan that had only narrowly escaped calamity. He writes down in his notebook: “Gingko tree (1,000 years old); old well (1,000); Chinese boxwood (1,000)—sacred tree; magnolia (800 years)—a white magnolia grafted onto a purple one; osmanthus (600 years).” On the reverse side of the page, he records the names of all the state leaders whose pictures hang on the wall.

As Gu emerges from the nunnery, he finds his companion hasn’t bought the bayberries after all; they have been spoiled by the rain. They get back onto the 627 bus for another 20 minutes. As they swing into the station, Gu jots down the names of the villages they pass: Xinjian, Jinwan, Chawan, Dabin, Yangwan, and Songxia.

As he finishes, they arrive at Lugang Ancient Village. Entry tickets are 65 yuan, but seniors over 70 can visit for free. Gu knows how ancient villages tend to look: decorated archways, narrow cobblestone roads, small bridges, and old stores with hanging brocade signs inscribed in calligraphy identical to their newer counterparts. It isn’t clear who they are trying to attract. Every store more or less palms off the same stuff to tourists.

Some of the old homes charge for entrance. Gu uses his senior pass instead. He enters them one by one, making a lap and recording the names of important figures, residences, and dates. He makes a note of an exhibit about a selfless former inhabitant who stumbled across 5,000 taels of silver currency and returned the whole lot to its rightful owner.

His companion steps out of a doorway and urges Gu to go inside the house and take a look. When Gu emerges, he sees no sign of the man anywhere. He has become a party of one again, but doesn’t find this so strange.

Gu decides to leave Lugang and heads back to the bus stop. The return journey begins at 2:40 p.m. Altogether, he thinks he has spent about seven hours on the road, so he should be back home at around 11 p.m. He’d intended to be back for dinner, since he didn’t normally go out in the evening. He and Shen generally eat dinner every day before dark and are in bed before 7 p.m., when the sky is still light, people are still out, and their hearts are calm. As the sky darkens, anxiety sets in.

The sky above Lake Tai looks overcast, with rain spitting down in fits. Gu takes a bite of a powdered-sugar gelatinous rice cake he has just bought in Lugang. The cakes are filled with one of his favorites—bean paste—and he soon starts on another. He plans to eat one more and save the remaining two for Shen.

He boards the 627 and asks the driver: “I want to go to Shanghai. How do I get there by bus?”

“If you’re hoping to get to Shanghai you’ll have to take the subway, OK?” the driver says.

“I came here by bus. I took six of them.”

“But why don’t you take the train back instead?” the driver persists. “The buses are too slow. You won’t make it there in time.” He tells Gu to get off at Qiaotou and transfer to Bus 502 all the way to the train station.

Gu mulls it over. It would be better to return a little earlier, and besides, some buses don’t run in the evenings, raising the risk that he’d have to find a place to stay or take a taxi—expenses too terrible to imagine, not to mention completely unnecessary.

If he still wants to visit Suzhou the next day, he should return earlier to get some sleep. He’ll feel energized, and it’s easy enough for him to head to Suzhou two days in a row—this is the way he rolls. As the bus passes through Mudu, he realizes that he now has a better grasp of the way back. Seeing a familiar name on the road home makes him want to boast: “Hey, I’ve been all the way to Dongshan!”

At 5.50 p.m., he alights at Suzhou train station and spies the bronze statue of Song dynasty minister Fan Zhongyan in the dusk. He copies down the inscription beneath the statue’s feet—“First is to be concerned about the world’s troubles, last is to rejoice in its happiness”—as well as the date of the station’s construction: 2012.

After purchasing a ticket for the 6:47 p.m. train back to Shanghai, Gu thinks of calling Shen to put her at ease. He scans the departure hall for a phone to borrow. The first man pretends not to hear him and glances back down at his phone. Next, a woman eyes him suspiciously and shakes her head. The third person doesn’t even wait for him to open his mouth before waving him away. “Forget it,” Gu thinks, as a man who turns out to be the second woman’s husband comes over to ask him what’s the matter.

The man calls Shen on his phone and puts Gu on the line. Gu exchanges a few words with his wife, hangs up, and thanks him. This brief episode won’t alter his or Shen’s belief that Gu doesn’t need a mobile phone. Who would he call? And who would call him? Moreover, Shen thinks it would be too much trouble to give out your phone number to everyone you know.

At 9:45 p.m., Gu gets off the subway and starts cycling home. From the Catholic church to the edge of his village, two rows of powerful streetlamps shine overhead along the highway. The ditches on either side have been sown thick with crops. Heads of millet brush the blue-black night alongside sweet sorghum, wild wheat, poplars, and clusters of trees, whose every leaf is illuminated clearly. The puddles are black but limpid, like the surface of a mirror, and rimmed with rings of twice-reflected gold. The image of the trees in the puddles is somehow more distinct than the trees themselves. Isn’t that funny? The scene doesn’t look this clean during the day, when the eye can’t ignore the trash strewn along the slopes, but lighted by 100 streetlamps, it is a joy to behold.

There is not a single car on the road; just Gu on his bike. This area never used to be this bright at night. In the past, the village and fields were blanketed in darkness. Little egrets stalked the shadows. The river did not shimmer, and vipers rustled the grasses. Years ago, Gu’s older sister was raped and killed while walking out on the road at night. The case went cold. Shen fears the dark and doesn’t go anywhere after sundown. She lives her entire life within 500 meters of her neighborhood.

The neighbors who have moved into new, state-subsidized apartments still ride electric scooters into the village to tend their fields. A new river, dug out of the sludge that now forms its banks, flows perfectly straight. The village where Gu and Shen’s neighbors once lived now lies buried under the mud, on which some of the relocated former residents have planted sweet potato that has grown rampant. One by one, row by row, flower by flower, the fields were sown with numerous plants. The ingenious locals have created this scene of beauty, over which tower high-voltage power lines.

As he draws up to his house, Gu is suddenly struck by the time years ago that a medium—someone who claims to communicate with spirits—visited the village. When the medium passed Gu’s house, she suddenly exclaimed: “Your daughter is walking beside you.” The women in the village kept this from Shen because she gets spooked easily. Instead, they told Gu, who has no such qualms, not even when he trimmed the hedge by the road near that very spot.

Is his daughter still nearby? She was born in 1970. She had loved beauty, worn dresses, and was living with her boyfriend in Shanghai in 1994, when Gu and Shen were told she had jumped off a building and killed herself. Although Shen believed she’d been murdered, there hadn’t been enough evidence to bring charges. Back then, as now, they didn’t have a phone. Shanghai seemed very far away, and they didn’t hear the news until the next day. If she had lived, she’d be 46 years old now. When Shen dries the corn, she still wears her daughter’s old sunglasses to dampen their dazzling brightness in the glare of the sun.

Gu surveys the indistinct little path before him, thinking today was somewhat tiring. He pulls the latch on the gate to the yard and closes it behind him with a creak. His day is coming to an end.

In total, Gu passed through 53 subway stations and 194 public bus stations today. He’d gone out for a little jaunt, and saw nothing heroic in it. He was a crack shot and a decorated grenadier. The people he thinks of as heroes are Dong Cunrui, Huang Jiguang, and sports champions. Many other old folks do what he does. It was nothing.

After some sleep, Gu is ready to go again the next day. By noon, he is stepping into Shenjiang subway station toward Anting Ancient Street. He ascends Yong’an Tower and visits the Bodhi Chan Temple in the rain. In the three weeks leading up to June 26, after which seniors in Shanghai no longer qualified for free public transport, Gu traveled on 13 of those days. Now that he can no longer ride for free, he relies on a 150 yuan monthly transport subsidy from the local government.

In the course of his life, Gu hasn’t really been anywhere. When he was 7 years old, he traveled around 1,000 kilometers from his father’s house in Hongkou district to his mother’s home in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province in central China. Since then, he has spent his life in the countryside near Shanghai, a city that for a long time was far enough away to feel like somewhere else. Unlike his relatively far-flung rural home, Shanghai represented Western-style architecture, cars, his bygone childhood, his father’s mistress, and his daughter’s boyfriend.

In 2013, Gu turned 70 and qualified for his senior travel card. Sadly, Shen broke her foot not long afterward and took more than a year to recover. Starting in the spring of 2015, Gu started using his senior card to explore his local area. He went to Suzhou eight times and Luzhi twice, and also made trips to Zhouzhuang, Qiandeng, and Jinxi. He made six or seven trips to Tongli and Zhujiajiao. He went to Qibao, Nanxiang, Sijing, Fengjing, and other places more times than is worth saying. On the last day he could ride for free, he went to Dongfang Lüzhou. He had originally wanted to go to Tongli, but that day the buses were packed with seniors all making the most of their last free rides, and he couldn’t squeeze on. Nonetheless, he can still say: “I’ve been to many places. I’ve been everywhere.” And he’d be right.

Author’s Note: Gu Cunxing is my neighbor in real life, and the story is based on him. He has filled up a number of notebooks just from jotting down lines after he sees a sports game, visits a new place, watches a free Shanghai opera performance or a movie, and other activities. Once, he casually told me he changed six buses to visit Suzhou. Mr. Gu is not very good at making observations or memorizing details, so I filled in the gaps in the story about his journey. At first, I found Mr. Gu’s experience unique, but later I realized that many seniors, like romantic teenagers, have been taking spontaneous rides all over the city simply because they want to see the world. I’ve also come to realize that for people whose lives seem peaceful and normal on the surface, there could be tragedies lurking underneath.

Gu Xiang (顾湘)

Gu Xiang is an author, painter, and translator who has been publishing her work since she was a teenager. Her book, Zhaoqiao Village (《赵桥村》), detailing her daily life after moving from Shanghai to her childhood home in a suburban village, won the Best Non-Fiction Prize of The Young Writer Awards in 2020. Born in 1980, Gu has a bachelor’s degree from Shanghai Theatre Academy, and a master’s degree from Moscow State University. She published her memoir about studying abroad, In Russia (《在俄国》), in 2020. Her poetic prose and quest to find an idyllic life in a fast-changing society strongly resonate with young urban readers.

June 23, 2016 | Fiction is a story from our issue, “Upstaged.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.