Steven Schwankert talks to TWOC about his documentary 'The Six' and the lost history of Chinese passengers on the Titanic

A Titanic story with a China angle seemed almost too good to be true for Steven Schwankert, a New Jersey-born shipwreck enthusiast and an author and researcher who has lived in China for 25 years. But that's exactly what he stumbled upon when online searches led him to images of a single ticket for the ill-fated ship, crowded with eight Chinese-sounding names.

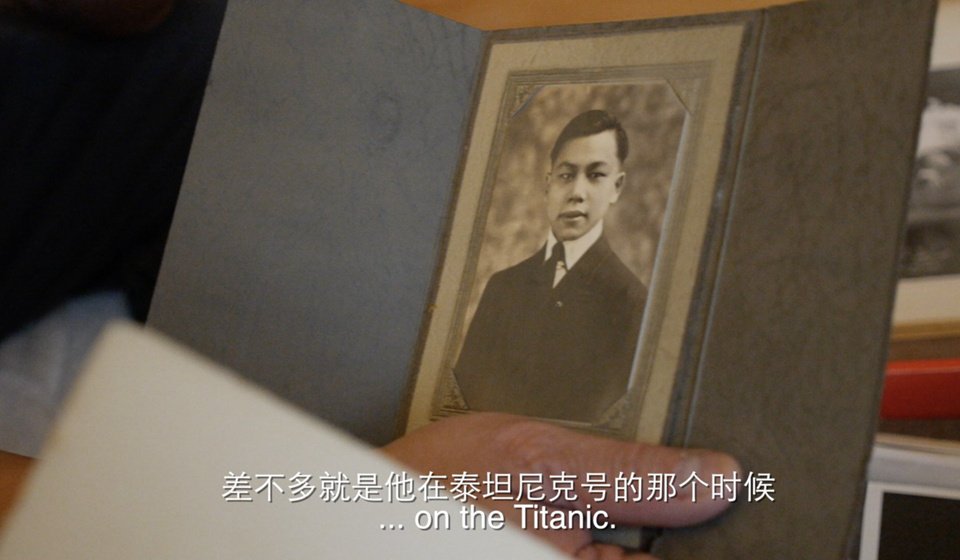

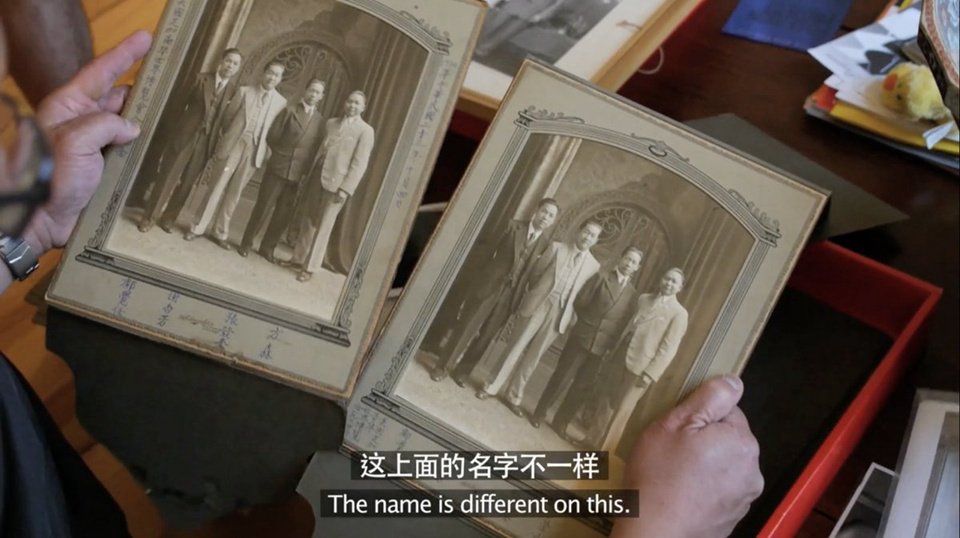

Further research revealed that six of these passengers had survived the sinking. By the time Schwankert and his long-time collaborator, director Arthur Jones, started piecing together the survivors' stories into a documentary and book project, the 100th anniversary of the Titanic's sinking had passed. Schwankert was convinced somebody would have come forward by then and claimed descent from one of the Chinese passengers on the ship—but nobody ever did.

As self-described "historical optimists" who refused to believe that the Chinese passengers' stories were destined to remain riddles, Schwankert and Jones set out to uncover traces of the six men who survived the disaster on April 15, 1912. This headstrong passion launched them on a turbulent research journey that spanned four countries and culminated in a documentary, The Six (2021), released in China close to the 109th anniversary of the disaster on April 16, 2021.

The documentary takes audience members across China through the history that Schwankert and Jones set out to unveil, as well as their process of piecing it together. Along the way, they reveal the wider history of Chinese immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which required the Chinese survivors to leave the US within 24 hours of landing in New York on the rescue ships—and likely contributed to the loss of their story.

Fresh from a tour around China to promote the film, and now preparing for the release of a book of the same title on the same subject in June, Schwankert shares with TWOC his thoughts on the surprising stories he uncovered.

How did making a documentary film affect your research process (and vice versa)?

Although it's a documentary, we like to think of it as a historical detective story, too.

Part of the human story Arthur wanted to capture was about the researchers. He wanted to capture not just our successes, but also the moments when we were frustrated about hitting a dead end, when we thought we were not going to find what we set out to find—when historical optimism meets cold reality.

Sometimes Arthur is a little too true to the fact. I would have liked him to stop rolling for a second and say, “Steven, you look like Boris Johnson at this moment. Just fix your hair a little bit, you know?”

What was the experience of research like for you?

If you think of the Titanic's history as a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, an opportunity to put one or two of those pieces in place is exceptional. But the story became something bigger, which was surprising. I didn't think that anything could end up being larger than the Titanic disaster.

We got to really look at how the tides of history pushed these Chinese survivors back and forth—from Southern China, to Europe, North America, and then back to Europe, and so forth, through world wars and immigration policies that welcomed or didn’t welcome them.

The funny thing is, I think the people to whom the Titanic aspect of the story may have mattered the least were the survivors themselves. People ask, how come they never told the story to anybody else? Over time I’ve come to the conclusion that maybe they just didn’t see it as that important. Maybe they saw it as: "Well, this happened, I survived, and I kept going forward in life." And that was it.

That says a lot about their spirit of perseverance, which to me was really inspiring. There were definitely moments when we were frustrated in the research process. But in those moments, we just thought of these individuals and everything they had to go through. Us not being able to find a name is not really a big deal in comparison.

What kind of connection did you feel between the survivors and yourself?

When you start to get involved with people's families, and they start to share things with you, it becomes a different kind of responsibility. Although it is frustrating to not be able to meet our research subjects, the survivors, in person [since they had all passed away], I just hope that we were responsible custodians of their story.

While down south [in China] in Taishan where Fong Wing Sun, our main survivor, was from, we just showed up at people’s doors as this mixed group of foreign and Chinese crew, with cameras and boom mics, quite like a walking press conference. But it was surprising how unfazed people were by all of this. For example, in the film, a gentleman said, “I have some letters from him.” Then he walked out with a pail full of letters, on one of which was a poem Fong wrote about surviving the Titanic. It was mind-blowing.

We think that we live in this digital age where you can just type in keywords in Google or Baidu, and the history of the world lies before you. But if you're trying to tell a human story like this, you still have to go where the people are, where they live, walk, and work. That’s why we ended up in four different countries and 20 cities for this project. You'd never make the discoveries like the letters and poems if you didn't go there, because those are things that people don’t just share over the phone, email, or WeChat.

When you show up in person, you're really demonstrating that you're making the effort to do a good job and to be true to the story as much as possible.

What made you so interested in maritime history?

The ocean was always part of my life. Growing up along the New Jersey coastline, which is home to many offshore shipwrecks, I was always aware of the sea and that ships are lost in it.

One of the first things I ever remember seeing on television was a show called the Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, the inventor of modern scuba diving. From when I was 3 years old, I used to watch it every Sunday night. The passion for the ocean became something that never changed. I didn't get distracted by dinosaurs or cars or whatever 3-year-old boys move on to.

But I have to say one thing that did distract me from all of that was when I started to become interested in China.

What's the story between you and China?

It was in 1985 when I, not quite 15 years old, first came to China in a tourist group. I was thinking about going into writing and journalism. After the trip, I thought, wow, if you went to China, you'd never run out of things to write about. That has been 100 percent true since that moment, and there's no chance of that not being true in the future.

There are movements emerging in response to racial discrimination against Asians in the US and around the world. Was it deliberate to have this film come out during this time?

No, it wasn’t. The film was supposed to come out at this time last year, but cinemas here in China were closed [due to Covid-19]. I don’t want to say that our luck was good in terms of the timing, because I wish these events, especially the violence, didn’t have to happen.

But at the same time, I hope that the film can help show that these are not new problems. The Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted in 1882. It’s not like suddenly yesterday some people in the US realized they didn’t like Asians. These sentiments have been around for a long time and they’re not something that will be resolved quickly, as unfair as they are. I think the door to the United States should always be open for people who are willing to work that hard for their dreams.

I hope that on one hand, the film could help us realize we need to think of different ways to confront these long-standing problems. But I also hope that people look at it as a story of hope—that you can overcome big obstacles, whether it's an iceberg in the middle of the North Atlantic or anti-Chinese policies and sentiments.

How can a project like this, which retraces and reshapes a historical narrative, impact how the present and the future are perceived?

Anything that gives people a greater understanding of a situation has value. A lot of audience members here have shared with us that not only did they not know about Chinese passengers being on the Titanic, they also didn't really know anything about the Chinese Exclusion Act or the head tax in Canada.

I don't want people to think that we just made a film to show people in China how badly they've been mistreated in the last century, but I think people need to understand and accept that those things have happened and know that they were mistakes. Let's not repeat that mistake. Let's not exclude people just because of the way they look or because of where they come from. That is not what we represent.

The film is not meant to be particularly critical of anyone, but these things are indeed history, and they are now well-documented.

Cover image from VCG