Artistic voyeur Song Yonghong paints scenes of everyday intimacy in Beijing

Beijing-based artistic voyeur Song Yonghong thrives on the complexities of life in everyday settings. Although there’s a lot of sexual intimacy in his work, the participants give off a sense of detachment—the intense stares of American Gothic meeting the lonely streets of Edward Hopper.

A Hebei native, Song received his training from the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, graduating in 1988. Like many artists working in the 1990s, Song was among a new group of artists who moved away from the rebellious ideas of the ’85 New Wave—a grassroots avant-garde art movement that developed across China in the 1980s, experimenting with Western modern art and political liberalism—toward the subdued satirical forms of Cynical Realism, commenting on society through gentle humor. Avoiding the stagnant teachings of mainstream art colleges, Song relishes the fleeting moments of the everyday, spotting the absurd and uncertain amid the confidence and seriousness of modern China.

What differences are there between your work and the 1985 New Wave art movement?

A lot of the artists in the ’85 movement are much older than me, and they tend to be more concerned with the bigger political and historical issues that happened before the 1980s. For me, these issues are too abstract and don’t feel real. I’m more concerned with things that are tangible to me, things that I can personally perceive and experience.

How do you select what you want to put onto canvas?

My sources of inspiration are what I encounter on a daily basis. I will draw these moments, and these drawings can consist of what I’ve seen on TV, the people I meet on a regular basis, or personal encounters I have had. But sometimes these drawings don’t translate into work on canvas. Some of them stay as drawings for a long time, and then I will recycle and revisit them to integrate them into a work of art.

Can you give some examples?

Sure! Take Moat Around the Forbidden City (1994) [depicting one corner of the moat surrounding Beijing’s Forbidden City, with a graphic image of a couple in flagrante in the foreground]. The area was known, through reports and novels, for clandestine dates in the 1990s, as was also the case in public parks. The 90s wasn’t like today, when a couple can just go to a hotel and get a room. Everybody knew there were places, like parks, where you went to date, but it was more interesting to me to portray dating in that setting. There was tension between the traditional architectural context of the Forbidden City and the private encounters of amorous couples.

Then there’s Production Line (1994). This comes from one shot from a TV news clip of factory officials inspecting a meatpacking assembly line. I took it and ran with it. These people make up a kind of hierarchical social structure of China today—you can see from where they are standing who is the most important figure, then his subordinate, the subordinate’s deputy, and so on. All this elaborate formal bureaucracy, when all they’re inspecting is chickens [a euphemism for prostitutes, and an indicator of corruption and sleaziness]!

Light (1998) was based on an experience everyone had. During the reform and opening-up period, if you were walking alone after dark, it was very common to have a flashlight thrust into your face by others. It made people feel safer if they could see your identity. I thought it would be interesting to take this sense of distrust and counter it with some of the reasons that fueled distrust: the videotape the man is holding is pornography!

Your work frequently features sexual themes. What does sex mean in your work?

It shows contempt for the social status quo. From the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, all the way to reform and opening-up, state ideology reduced people’s individuality, their ability to envision what they want out of life. Even in the 1990s people were still bystanders: They didn’t have the impulse to act upon their desires. For me it was valuable to paint these works because they expressed my desires, the things people are too shy to reveal.

How does China today compare with China in the 1990s?

The 90s were a lot simpler. Today, it is more materialistic. Our thoughts are more scattered and fragmented than before. In the 90s there was more of a sense of hope, whereas now we’ve come to a sense of an apocalypse, a social despair. I can’t explain the specifics of what the despair is, but I just feel that that’s the zeitgeist.

Critics have said your earlier works display anger and an emotional uncertainty about modern China. What are your thoughts about that?

For me, my essential drive was to challenge what I was taught in the art academies, which was heavily enforced by state ideology and didn’t explore expressive themes and criticism of society. In my practice, I try to express a sense of personal creative freedom, rather than what is conventional, ideological, and utilitarian art. I wanted to elaborate on the circumstances of a time.

If you really want to talk about anger, it was directed more toward the mainstream value or the state ideology that promoted this kind of mindless optimism. My work tries to show that life today isn’t either good or bad—it’s just life. I want to focus on everyday individuals rather than this hyper-ideology, the stories that are left untold.

Also, society is not transparent, which means people aren’t integrating. If you notice there is a lack of feeling in the eyes of most of my subjects. It gives a dehumanizing feel—even when people are present, they’re not engaging with each other. Ideology has reduced people into having no personalities.

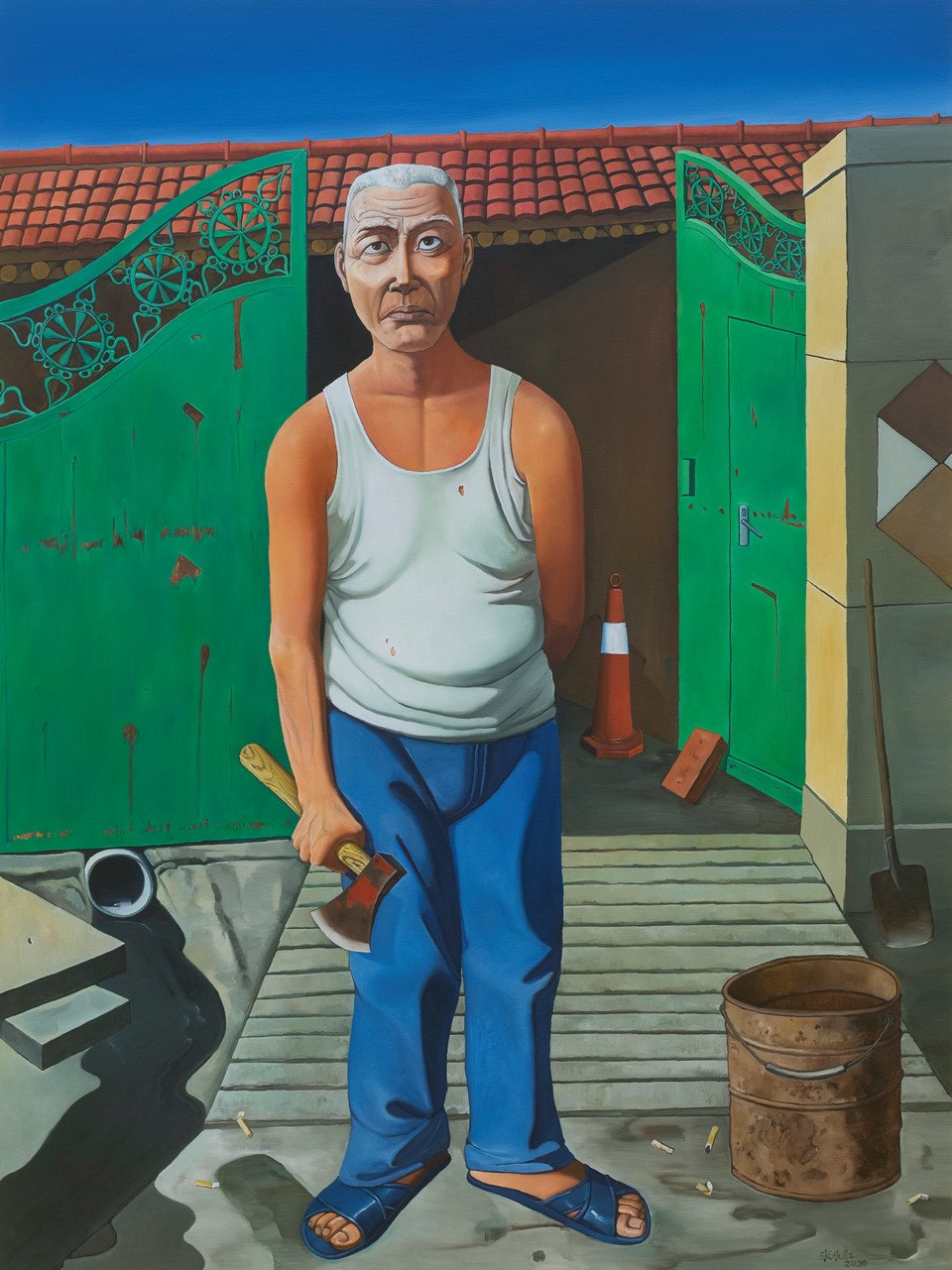

There are too many paradoxes and dichotomies in modern China—it gives society a sense of absurdity that I try and bring out in my paintings. The Neighborhood (2020) is based on Songzhuang, the village where I live. The villagers are very hostile toward outsiders, which the man holding an axe emphasizes. They’re not necessarily welcoming to artists who occupy certain houses in the village. Yet these are people who are being left behind—although they are just 18 miles from Beijing’s city center, their community feels like it hasn’t changed at all [since the 1980s]. So disadvantaged communities or individuals can become sources of social hostility. I feel it’s absurd that despite all our technological advances in recent years, Chinese people’s psyche hasn’t advanced as much as our reality has.

Images courtesy of Hunsand Space and Song Yonghong

Canvassing the Neighborhood is a story from our issue, “Dawn of the Debt.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.