For over a decade, experts have been examining cryptic bamboo slips that may contain a lost version of Chinese history

Much like the Trojan War in Homeric poems, early Chinese history is often retold with dramatic elements designed to engage the audience.

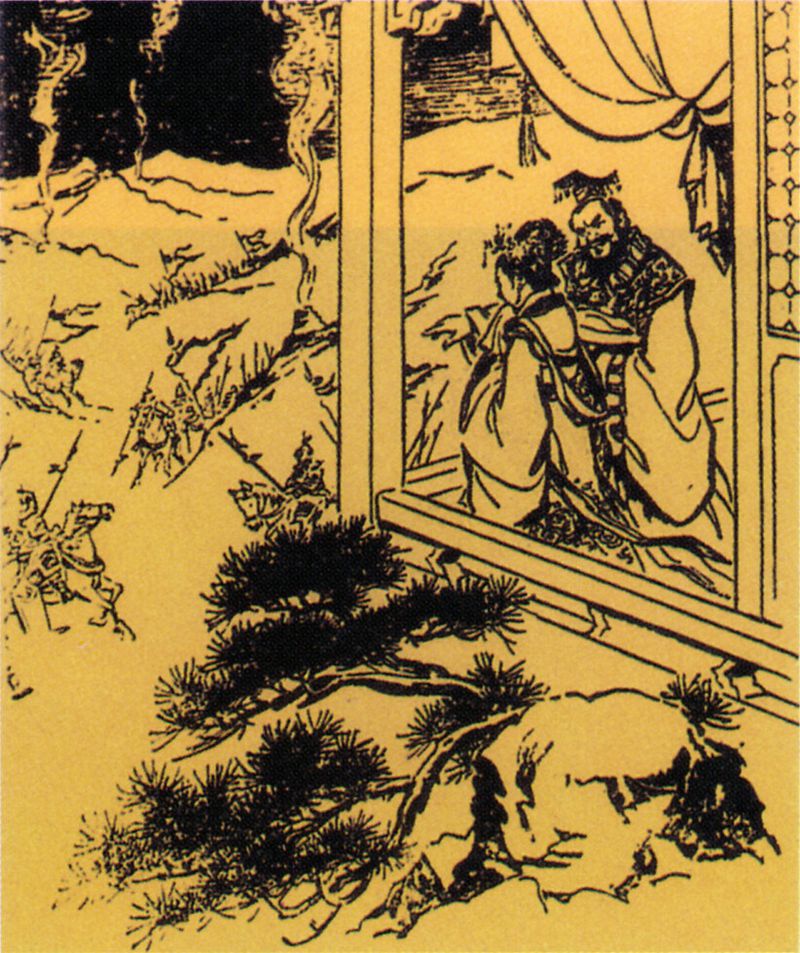

For instance, it’s commonly believed that a concubine named Baosi (褒姒) caused the fall of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE). According to legend, King You of Zhou (周幽王) wanted to entertain the famous beauty, so he repeatedly sent false alarms of invasion to the lords of his vassal states, calling them to his aid. When real enemies attacked, no one believed the king’s SOS calls, and none came to his rescue.

Recorded in Master Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals (《吕氏春秋》) and Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), the story served as a cautionary tale for over 2,000 years—until modern archeological studies offered an alternative version of history.

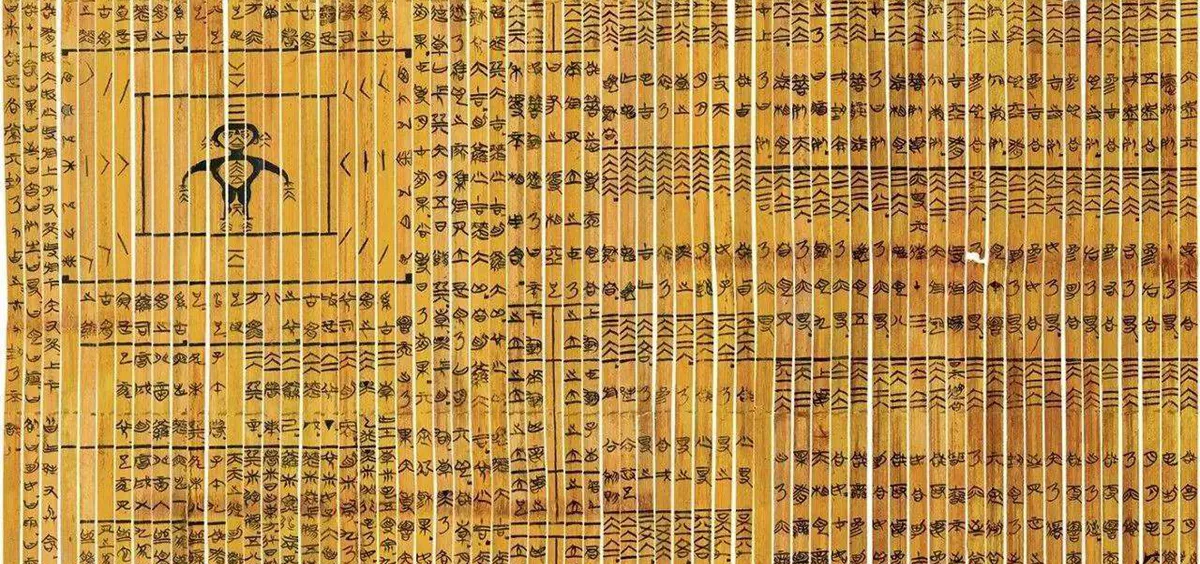

In 2008, a batch of over 2,300 ancient bamboo slips of unknown origin were donated to Tsinghua University. Prior to the invention of paper, texts were written vertically with brush and ink on long, narrow strips of bamboo or wood, which were strung together and rolled up to create books.

Eleven top archeologists, historians, and paleographers from the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong examined the find, and concluded that these ancient strips were historical records from the late Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE). Their contents had never been seen before, “not even by the Grand Historian [Sima Qian, c.145 – c.86 BCE] himself,” the late Tsinghua historian Li Xueqin allegedly told his superiors at the time. These “Tsinghua Slips (清华简)” have been carbon dated to around 305 BCE.

An illustration of King You of Zhou and Baosi, amused by the lords they tricked to come to their rescue (VCG)

The discovery of the Tsinghua Slips caused an earthquake in academia, as their contents had the potential to overturn our modern understanding of ancient historical events, philosophy, literature, and language. Since 2010, researchers have published content from these slips at the rate of one volume per year, and estimate they will put out 15 to 16 volumes in total.

One historical record in the Tsinghua Slips, titled Chronicles (《系年》), puts forth an alternative explanation for the collapse of the Western Zhou: King You’s queen was a princess of the Shen state, and had a son named Yijiu (宜臼). But the king favored his other son, Bopan (伯盘), by his concubine Baosi, and wanted to make Bopan his heir. Yijiu fled to his mother’s home state for fear of his life.

King You and Bopan waged war against the Shen state, which allied with a nomadic northwestern tribe called the Quanrong (犬戎). Both the king and Bopan were killed in the battle. But Yijiu wasn’t immediately enthroned as the new king as previously believed: In fact, King You’s younger brother assumed power and started a 21-year civil war, until Yijiu triumphed and became King Ping, the founder of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770 – 256 BCE).

Such new findings abound from the Tsinghua Slips. There is even an ancient calculation chart, believed to be the oldest decimal multiplication table in the world.

The most prominent discovery are eight new essays from the Shangshu (《尚书》, Book of Documents or Classic of History), a collection of rhetorical prose of ancient rulers. One of the five Confucian classics, Shangshu has served as the basis for ancient Chinese political philosophy for over 2,000 years. It is also at the center of an ancient debate.

One of the books burned by China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) around 213 BCE, the Shangshu most are familiar with today was merely a recording of 29 essays that a scholar recited from memory when the Qin’s rule ended. Over the millennia, many versions appeared claiming to be the original, but have all been disproven.

So far, historians have deciphered eight brand new essays from the Tsinghua Strips that are believed to come from the original book, Some confirm existing knowledge of the book’s content, while others offer exciting new information about historical figures and places.

However, the origin of the Tsinghua Slips remains a mystery. Donated by an alumnus of Tsinghua, who purchased them in Hong Kong, these slips were most likely excavated illegally and smuggled out of the mainland. To keep them moist, the slips were stored in rolls and wrapped in plastic films when they first arrived at Tsinghua, and appear to have been preserved in water for thousands of years. Scholars theorize that they were excavated from a tomb in southern China, mostly likely in the territory of the ancient Chu state in Hunan or Hubei province, where similar bamboo slips have been discovered.

The size of the bamboo slips varies. Some are 46-centimeters long, while others are pocket-sized, or around 10 centimeters in length. Judging by its style, the text was written by a number of master calligraphers. After careful cleaning, researchers preserved the strips in distilled water and stored them in a lab with controlled temperature and light.

To whom did these bamboo slips belong? The content, cross-referenced with historical documents, seems to suggest the owner was a historian or an official with a passion for studying history. Unfortunately, scholars won’t know for sure until more details about their discovery surfaces.

In the meantime, in order to share this priceless resource with a larger community of scholars, the Tsinghua team is working on a revised edition of the deciphered text that will be published by The Commercial Press in 2022. An English edition will be translated by a team led by Professor Edward L. Shaughnessy of The Creel Center for Chinese Paleography at the University of Chicago, and published by The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Cover image: an excerpt of the Tsinghua Slips containing an illustration of the baga, a Daoist symbol, courtesy of the Tsinghua University Art Museum