More memories of Wuhan before the siege

Wuhan has become world famous as the origin of the coronavirus outbreak, but the central Chinese city has much more to offer. Previously, we published anecdotes by TWOC staff and friends that showcased what they love about the city: Part 2 of the series is published below.

We are still looking for reader contributions, so if you have your own “Wuhanecdote” to share, let us know in the comments, on social media, or by emailing editor@theworldofchinese.com!

Kiran Gautam, publisher, South Asian edition

I never had any intention of visiting Wuhan, but in 2009, Wu Lin, my father’s translator, suggested that I make a courtesy call on Zhou Baiyi, a famous Wuhanese writer and a good friend of my father. I feel like it was just yesterday that I arrived at Hankou Railway station, but it has already been 11 years.

Eleven years ago, Wuhan was being dismantled: old houses being pulled down, flyovers going up, and an underground metro system breaking ground, all under the slogan of “Wuhan: Different Every Day.” Since then, I’ve visited the city whenever I have a chance. We just held Hubei Media Week in Kathmandu in November 2019, where I hosted high-level delegates from Hubei, and my thoughts are with all the friends in China I’m connected with through WeChat

Wuhan is home to several “book cities,” or mega-bookstores (VCG)

Hubei Zhongtu Chanjiang Culture Media has been a very good business partner for me, as we have been promoting Nepali art, handicrafts, coffee, and tea through its 6889 Bookstore. My work has been very much linked with Hubei ever since I got to know so many friends there from 2009. You can say Wuhan was my launching pad to the Chinese mainland. The China (Wuhan) Periodical Fair was the turning point of my career, where I got connected with so many Chinese media and publication houses.

Although the 6889 Bookstore is at the epicenter of the outbreak, it has kept updating its microblogs with articles related to the virus and recommending books for children to read. Giving positive energy at time of crisis is something I really admire.

Hatty Liu, managing editor

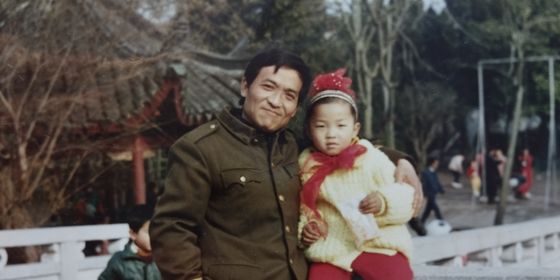

In 2013, Wuhan’s officials embarked on a widely mocked campaign to transform their city into a “new New York.” Yet residents of this central Chinese city have much in common with their stereotypically sharp-talking, fast-driving American counterparts. Visits to my grandparents’ home in Wuhan terrified me as a child, for they always began with a death-defying ride from the train station on buses that lurched across the lanes like Formula One racecars.

In my nervous memories, two aggressive features of Wuhanese speech stick out: the habit of addressing all and sundry as “唉 (Hey)!” and a knack for making the most innocent remark sound like an accusation. The first time my eldest aunt from Wuhan visited my parents’ home the US, I remember showing her to the upstairs guest bathroom, and hearing her voice crack the air behind me like a whip: “唉,你有几多厕所嘞!”—literally “How many bathrooms do you have,” but it sounded more like, “Why the f—- do you have so many bathrooms?” “Four,” I answered in a mortified half-whisper.

On April 9, 2017, a rainy Sunday following the first Qingming Festival after my grandparents’ deaths, my mother and my other aunt ran Wuhan’s second-ever citywide marathon. The route showed off Wuhan’s choicest landmarks—from Hankou’s historic Bund to Turtle Mountain, across the stately Yangtze River Bridge to Yellow Crane Tower, the Wuchang Uprising Memorial, and East Lake—and an astonishing 22,000 people found their own motivation to power through the miles.

My mother and her sister ran in memory of their parents, eager young engineers who’d come from Beijing to build up Wuhan’s telecommunications sector in the 1950s. Others raced while hoisting flags for heart disease research or their graduating class, or, unabashedly, in order to load up on the re gan noodles, tofu skin, and spicy crayfish that rewarded finishers at Chu River Han Street.

Many local running clubs joined in the race (VCG)

In all, it was another reflection of Wuhan’s hotblooded ethos, now revealed to me at its best and most inspiring. Moved by the crowd’s rapport, my father and I joined with over 80,000 spectators’ shouts of “加油!” as our family members raced past, while a cynical senior jeered at us from nearby. “走几多路,就看那么一滴 (Come so far just to watch a few seconds),” he grumbled, stretching out the vowel in “那” only as the Wuhanese can. But I could tell he wasn’t really angry—for he, too, had come out at 8 a.m. in a drizzle to celebrate the city he loved in his own ferocious way.

Sam Davies, editor

“Wuhan: Different Every Day”—that was the much mocked marketing catchphrase plastered on promotional billboards across the city during my time studying there from 2016 to 2017. The phrase was meant to capture the dynamism of a city changing rapidly, and to entice tourists to the (allegedly) large variety of attractions.

It was also used by locals, and adopted by me and my friends, to brush off anything strange or undesirable. Dorm flooded? “Wuhan: Different Every Day!”

More than the extraordinary or the different, though, it’s something routine that looms largest in my memory of the city: my breakfast ritual. Each morning without fail before class, I would order the quintessential Wuhan snack, “hot dry noodles” (热干面) from a little stall en route to the classroom. The nutty, oily taste of the noodles was heaven, while the kick of spice was, surprisingly, just what I needed in the morning. At 4 RMB a go, I had found my breakfast for the year.

Wuhan is known for its diverse breakfast food selection, including hot dry noodles, tofu skin, and pan-fried dumplings (VCG)

As my Chinese slowly improved, I began to chat with the owner each morning. She was not from Wuhan, or even Hubei province, but a migrant worker who had left her 9-year-old son at home in the countryside with his grandparents. She was saving money for his school fees, and intended to send him to university. The two of them would often be video calling while she dished out the noodles. I hope they are together now, and safe.

A Korean classmate of mine adopted the same breakfast routine, and we bonded over those bowls of noodles. I spoke no Korean, and he almost no English, but our Chinese slowly improved together and we developed a close friendship that continues today. Those cardboard pots of carbohydrates and spicy sesame sauce almost certainly constitute the best 4 RMB I’ve ever spent, and spent, and spent again.

Right now, I imagine many people in Wuhan are desperate to return to whatever used to be their morning routine before the virus outbreak, to again enjoy the simple pleasure of breakfast on the way to work or school. I hope that can soon become reality.

Cover image of Hankou’s historic Lihuangpi Road from VCG