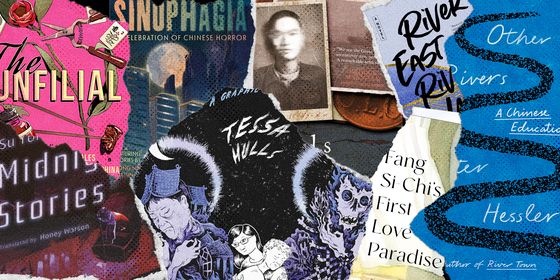

A beautifully illustrated book for young readers tackles China’s complicated modern history

Chinese modern history—with its United Fronts and constant conflict—can be a rather dense and intimidating topic, especially for middle and high school students.

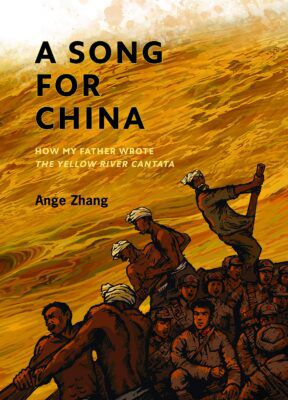

Yet, this is the exact audience writer and illustrator Ange Zhang reaches in A Song for China: How My Father Wrote the Yellow River Cantata, a new 80-page hardback nonfiction book on the man whose poem inspired one of the best-known works of Chinese revolutionary music.

The story begins with the birth of Zhang’s father (known mostly by his pen name Guang Weiran) in Laohekou, Hubei province. The early pages and illustrations show Guang’s journey from an obedient and scholarly child to a radicalized preteen following the May 30th Massacre of 1925, when a group of protesting students were shot by foreign police in Shanghai’s foreign concession. A year later at the ripe age of 13, Guang became a member of the then underground Communist Party.

Despite communism still being a sensitive subject at some educational institutions in the West (especially for youngsters), Zhang does not shy away from his father’s revolutionary identity. Zhang’s illustrations, black-and-white woodcut prints with bright splashes of red, harken to the heyday of proletariat art. (The New Woodcut style, started by scholar Lu Xun who used the medium to expose social ills, was readily adopted by the Communists in their Yan’an headquarters in the 1930s and 1940s due to its cheapness to produce and ease of copying.)

Some illustrations, such as a group of Chinese with clenched fists, are highly political; while others are deeply emotional, such as when Guang embraces his mentor for the last time. In one picture, readers see the fear of the young Guang as he is interrogated by a group of Nationalist soldiers with bayonets attached to their rifles. In another, Guang sits in a fetal position, sobbing over the death of his Communist friends during the purges of the 1920s.

Able to evade persecution because of his youth, Guang entered Wuchang University to study Chinese literature. However, when the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1931, he found himself moved to act yet again and began to write patriotic dramas. His lyrics to “Flowers of May” (“the flowers of May are blooming in the field, beneath the flowers the patriot’s blood is flowing…”) became a rallying cry for those resisting the Japanese. It also made him a target.

Becoming the Publicity Commissioner of the Northwestern Battle Zone, Guang traveled constantly. In October 1938, at the age of 24, when Guang and his troops happened across the massive Hukou Waterfall of the Yellow River, he was inspired to “write a set of poems to express his admiration for the great Mother River of China.” He was further moved by a wild and dangerous ferry journey across the Yellow River to join the Communist Army. After arriving in Yan’an, Guang wrote the poem in five days; another six days later, it was transformed into an eight-movement cantata by French-trained composer, Xian Xinghai.

The Hukou Waterfall at the intersection of Shanxi and Shaanxi

Adding to Zhang’s illustrations are family photographs that bring the characters to life, as well as scanned scribbles of Guang’s original poem. To explain the more complicated twists of Chinese history, Zhang has written sidebars that describe the political and military happenings of the era in clear and concise language. Zhang’s illustrations take on new life at the end, where a new English translation of the lyrics of the Yellow River Cantata is represented through dramatic artwork in vibrant golds and yellows.

In the book, Zhang claims that his father’s Yellow River Cantata “represented the voices of the Chinese nation” and “expressed the will and determination of the Chinese people to defend their motherland against the enemy.” While it is easy to take the title at face value, A Song for China is much more than a book about a standard in China’s classical music history: It is an educational book about an entire era.

Yellow River Cantata is frequently performed throughout China

Cover image from VCG

Nominate a book for us to review! TWOC is seeking submissions from readers and publishers to its “Best Books on China” lists, part of the “China Bookshelf” project on bringing the best Chinese and China-relevant publishing overseas. Send us your picks to editor@theworldofchinese.com or through any of our social media accounts.