After a ‘Miserables’ beginning, can Chinese musicals finally make rent?

When tickets for the musical Letters sold out within a minute of going online, no one was more surprised than its lead actor Zheng Yunlong, who had promoted the show on his Weibo account only to learn he was already too late.

It was the moment for which “I have been waiting for 10 years,” Zheng commented beneath his own post. Though recognized as one of China’s top musical performers, having won best actor at the 2018 Musical Academy Awards in Beijing, Zheng is probably used to seeing empty seats in the theater: He once played a show in Harbin to an audience of 10.

Back in 2017, as Chinese cinema took in nearly 60 billion RMB, musicals made just 217 million RMB. Shanghai, the largest market in the country, only has about 30,000 to 40,000 regular theatergoers out of a population of more than 240 million, as industry watcher Wei Jiayi told news site Jiemian.

After six years laboring in musical obscurity, Zheng’s own career took off when he appeared in the TV talent show Super Vocal, alongside 35 other professional musical and opera singers, telling viewers he signed up in hopes that “more people will learn about musicals, and be more willing to see a musical in the theater.” With a 9.5 rating on review site Douban, Super Vocal became one of the most successful variety shows of 2018 with Zheng, a finalist, as one of its biggest winners: His Weibo following increased from 2,000 to 830,000.

Though this burgeoning “idol culture” in musical theater is controversial—an irate reviewer on Douban believes that audiences drawn by the TV stars are not true musical fans—the boost to Zheng’s profile was undeniable. Since appearing on the show, Zheng has starred in two musicals; all of his 18 total performances have rapidly sold out, and his new fans seem likely to stick around.

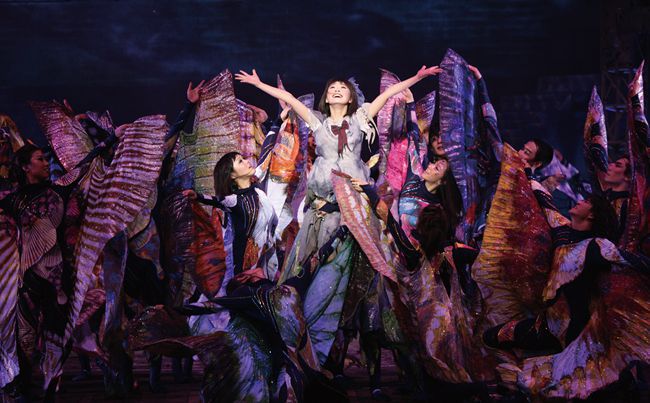

Scene of Butterflies

“Going to the theater is addictive,” an audience member surnamed Guo told TWOC after a production of Zheng’s Murder Ballad in Beijing in March. A recent convert to musicals, Guo said she already had tickets to see Cats and Romeo and Juliet later this year.

Compared to the first quarter of last year, ticket-selling platform Damai has reported a 28.6 percent increase in sales and six times the amount of revenue for a total of 517 musical performances, which include touring Western imports, localized translations, and—currently the least popular—Chinese originals.

The first Western musical performed in China was Les Misérables, which had 21 performances in its original language in Shanghai in 2002. Productions of Cats, The Sound of Music, and The Phantom of the Opera at the Shanghai Grand Theater followed. According to entertainment site D-entertainment, in 2015, 64.2 percent of the whole musical box office income went to imports.

The market for translated musicals has also been growing, as represented by a localized version of Mamma Mia in 2011 (which had Donna singing about going gambling in Macau, instead of Las Vegas or Monaco, in “Money, Money, Money”). Zheng’s most popular roles have been in Chinese versions of Broadway hits like Jekyll and Hyde and Man of La Mancha.

By comparison, there was only one original Chinese work in the top 10 musicals at China’s box office in 2017. When fans do talk about Chinese musicals, they are still discussing Butterflies, an adaptation of the folk tale “The Butterfly Lovers.” First produced 12 years ago, it won the Judge’s Choice Award at the Daegu International Musical Festival in 2008—the first time a Chinese musical won an international award.

The show’s producer, Li Dun, is displeased by this state of affairs. “About three years ago, I predicted that China’s musical market would see a boom. But I didn’t expect everyone would be doing imported works and translations,” Li laments to TWOC. “They think it’s easier than doing originals. But the fact is none of them are making money. The royalties are too high.”

By contrast, Li, known as the “godfather of the Chinese original musical,” has been concentrating on indigenous productions for over 30 years. In 1997, he produced White Snake, based on another classic folk tale, with famous musician San Bao. Regarded as the first Chinese musical, the play had 1,200 performances in Shenzhen.

Li and his team discussing the creation of Ah, Kuliang

Li’s other works also tell Chinese stories. In Love U, Teresa, the spirit of the late singer Teresa Teng helps a young musician follow his dreams; Ah, Kuliang is about an American who grew up in China and tries to return to the country after the Cold War; Papa, I Only Sing for You follows the relationship between a pop star and her foster father; Mama, Love Me Once Again tells about the bond and conflict between a single mother and her son out of wedlock. “We have such a long history and such rich cultural resources. There are so many stories we can tell,” says Li.

However, attempts to make musicals “embody Eastern aesthetics,” as Li puts it, have been fraught. Li recalls composer San Bao and Canadian director Gilles Maheau quarreling on the set of Butterflies. “The Westerners thought it was unbelievable that people become butterflies after death, while this plot device is well-accepted in China,” Li explains.

Audiences were similarly conflicted: During one show in Shanghai, a viewer took exception to the storyline and screamed, “You liars! This is not our ‘Butterfly Lovers!’”

Now, however, many ask Li when the show will be revived. “Maybe we did it too early,” says Li. “The audience need to be guided. It will be a long process, but someone has to do it anyway.”

Most Chinese buy tickets based on reputation, so every year “only the five most famous plays can get attention,” Wei, who is the chief editor of WeChat-based theater news outlet Haoxi, told Jiemian. This means Broadway and West End works, whether original or in translation, have the advantage.

However, Li insists original Chinese works are better because the translations are often bad in quality. “Sometimes, I feel the actors get depressed singing these poorly translated songs,” he tells TWOC.

Getting investment for such productions is a different matter, though: In 2019, an industry insider addressed as Xiao Si told Jiemian that the production cost of an original musical is usually ten times that of a common stage drama, but the return is highly uncertain. Most theater companies must rely on state support, which requires adhering to staid narratives and politically correct values.

The China National Art Fund sponsors 10 original musicals annually for a maximum 4 million RMB each, but “most of the money went to stated-owned companies,” Li noted. “And what plays are they performing? Just some empty, grandiose stories.” It’s not rare to see lots of money sunk into bad productions, he explained.

Lack of talent is another problem. Veteran actors are in short supply, thanks to the relatively brief history of the format, while younger actors lack skills. “The standard China’s theatre academies set for their students is too low,” San Bao told China Literature and Art Criticism magazine. “Musical students need musicianship, acting talent, and body coordination, but few students currently have all three.”

According to the Shanghai Conservatory Music, the number of students auditioning for its musical theater program increased by 46 percent this year. However, Li says few stay in the profession long, estimating that about 80 percent of musical performers end up changing their career—many lured by the higher pay of pop singing or film acting.

From the audience, there are also accusations of price-gouging. Seats for Zheng’s Murder Ballad cost 380 to 880 RMB in Beijing, but at its previous stop in Shanghai, the most expensive seat was only 280 RMB. “That’s the reality of our market; some people just can’t do things the right way,” Li alleges. “Sometimes, I feel like I am making musicals in hell.” (Zheng himself had obliquely criticized the unreasonable high price of his show on Weibo).

But Li isn’t giving up: He is still trying to stage a new original musical, Shen Nan Blvd—while coping with a last-minute loss of investors, another symptom of the immature market. “This is simply a test from heaven…the show will go on,” Li vows. “So long as people enter the theater, I’m confident I can make them stay.”

Images provided by Li Dun Studio

East Side Story is a story from our issue, “Funny Business.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.