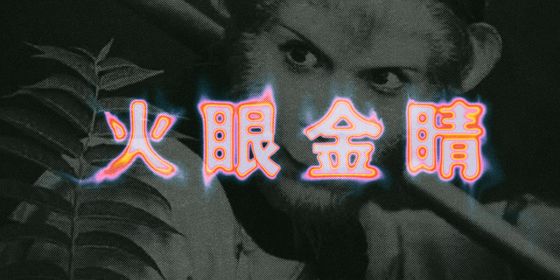

Literal and figurative phrases about fire

The Torch Festival (火把节, huǒbǎ jié), held from the 24th to the 26th day of the sixth lunar month each year, is a tradition of the Yi people and other ethnic minority groups in Sichuan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and southwest Yunnan. Falling on July 26 to July 28 this year, it celebrates the harvest with bonfires, torches, singing, dancing, and wrestling.

To mark the occasion, today’s chengyu will be themed around fire (火, huǒ). In Chinese, the character can mean a literal blaze, or be a metaphor for prosperity, a commotion, anger, or danger. Here are a few examples:

厝火积薪 Fire beneath the woodpile

In the Book of Han, Jia Yi, a wise government official and scholar of the Han dynasty, warns the emperor of the precarious state of his empire: “We are sleeping on a pile of wood placed upon the fire. The flames haven’t burned through yet, so we all feel safe.” Since then, this idiom has been used to suggest obliviousness to a grave danger.

抱薪救火 Fighting fire with firewood

Originating from the Shiji, this chengyu means to adopt the wrong measure to solve a problem, only to make it worse—like fighting fire with fire.

薪尽火传 A new flame ignites as the old one burns out

This idiom doesn’t stress the danger of fire. Instead, the character here has the meaning of “hope.” From the book Zhuangzi, the chengyu‘s original meaning was that “the human body is mortal, while the spirit never dies.” Gradually, it became used to describe the torch of knowledge being passed from teacher to student, or from one generation to the next.

烈火烹油 A raging fire burns oil

This chengyu from the novel Dream of the Red Chamber describes adding oil to a blaze to make it more intense. It’s used in a positive sense, to suggest making a good thing better.

火上浇油 Pour oil on the fire

This idiom sounds very similar to the above, but be careful—it’s a negative expression that describes making a situation worse, or fueling someone’s anger.

水火不容 As irreconcilable as water and fire

Fire and water often come together in chengyu. This one needs no explanation:

They are as irreconcilable as water and fire.

Tāmen shuǐhuǒ bùróng.

他们水火不容。

水火无情 Flood and fire know no mercy

This one describes the pitilessness of natural disasters:

Floods and fires are merciless, so people should raise their awareness of disaster prevention.

Shuǐhuǒ wúqíng, suǒyǐrénmen dōu yīnggāi tígāo fángzāi yìshì.

水火无情,所以人们都应该提高防灾意识。

隔岸观火 Watch the fire from across the river

The expression 观火 (guān huǒ, to watch a fire) appears in more than one chengyu. This one originates from the Qing dynasty and is believed to be one of the famous “Thirty-Six Stratagems” on warcraft and politics from an essay of the same name. It suggests that when conflict or trouble erupts in a rival camp, one should take time to observe how the situation develops, instead of rushing to take advantage. Now, though, the expression means “to look on somebody’s misfortune with indifference.”

When someone is in need, we should help rather than watch from the sidelines.

Dāng biérén yǒu wēinàn de shíhou, wǒmen yīnggāi shēnchū yuánshǒu, ér búshì cǎiqǔ gé’àn guānhuǒ de tàidù.

当别人有危难的时候,我们应该伸出援手,而不是采取隔岸观火的态度。

洞若观火 See something as clearly as a blazing fire

This expression describes someone of great insight:

He has a thorough understanding of the present situation.

Tā duì dāngqián de júshì dòngruò guānhuǒ.

他对当前的局势洞若观火。

Cover image of a Yi Torch Festival celebration in Liangshan, Sichuan, from VCG