The Nationalists’ fateful, tragic decision to blow up the Yellow River’s dikes in the war against Japan

Known alternately as “China’s Mother River” and “China’s sorrow,” the mighty Yellow River has nourished the northern plains as well as claimed countless lives in the course of its meandering, muddy history.

One of the river’s most notorious tragedies, however, was not the result of nature’s indifference, but human beings.

On September 18, 1931, Japanese militants blew up a section of their own railroad near Shenyang, blaming Chinese saboteurs. This event, known as the “Mukden Incident,” became the pretext for putting China’s northwest and its 30 million people under the control of Tokyo.

By 1938, the situation had become desperate—perhaps more so than at any other point in Chinese history. Japanese troops had invaded China proper, occupying Shanghai, Nanjing, Xuzhou, and Kaifeng, and were moving inland to Zhengzhou, the last major stop on the railroad before the wartime capital of Wuhan.

Standing in their path was the Yellow River, or Huanghe. Throughout its existence, the fast-flowing river has deposited large quantities of loess onto the flat lands in its lower reaches. This raised water levels, and required the stone-and-earthen dikes on the riverbank to be periodically topped up by local engineers. The resulting vast body of slow-moving water—flowing over sediment fill, propped high above stretches of adjacent farmland—posed a constant threat of flooding.

The second-deadliest flood in human history (after 1931’s Yangtze River floods) had occurred on the Yellow River in 1887, when heavy rainfall caused breaches in over 2,000 feet of dikes near Zhengzhou, drowning some 900,000. Now, with the Japanese en route to his capital, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of the Nationalist government looked to the destructive capabilities of the Huanghe to cut off (and hopefully decimate) the enemy, but at considerable cost.

It was not the first time environmental warfare had been used in Chinese military campaigns—in 1642, the Ming flooded China’s then-capital Kaifeng to prevent its capture by a rebel peasant army. Thus, on June 9, 1938, Chiang gave the order to blow up a 17-kilometers dike at the Huayuankou area, north of Zhengzhou; “substituting water for soldiers” against the Japanese advance; and turning central China into muddy graveyard.

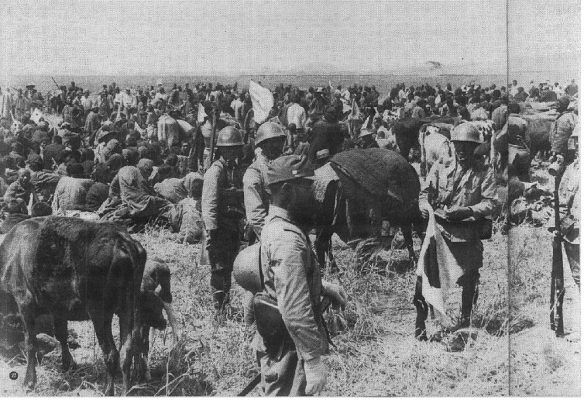

Refugees escaping invaders, looters, and destitution (via DisasterHistory)

The Great Flood of 1938 would prove the third worst in history, with 890,000 dead according to the official tally. Over 1.4 million homes and 8 million mu of farmland were destroyed in Henan province; an additional 11 million mu of land was devastated in nearby Anhui and Jiangsu. Over 4.8 million people lost their livelihoods, most them Chinese peasants living in areas still occupied by Nationalist troops, resistance fighters, and bandits, despite being under nominal Japanese control.

A military engineer, who worked on the project described in his diary how “exciting” it was, even as his “heart ached,” to watch the Huanghe rush like “10,000 horses” into the broad floodplains below, wiping out crops, dwellings, villagers and all who stood in its way. Nearly 3 million people were displaced by the floods as they fled marauders, starvation, and waterborne diseases in the heat of summer. The flood is also believed to be an indirect cause of the Great Famine of 1942, which claimed 3 million lives in Henan province alone.

Mainichi newspaper published this photo depicting “refugees rescued by Japanese soldiers” (Wikimedia)

And for what? Tragically, the Great Flood of ’38 (known rather blandly as the “Huayuankou Embankment Breach Incident,” or 花园口决堤事件, in Chinese) had almost no impact on the Japanese advance, despite its human toll. The Japanese military was largely out of range of the brunt of the flood, and reconfigured their advance from a north-south land crossing to an amphibious attack along the Yangtze. This caused the Nationalists to relocate their wartime capital again, from Wuhan to Chongqing, and allowing the former to fall three months later in October with far less consequence than if the flood had never happened.

The move into the mountainous southwest did leave behind a waterlogged central China untraversable by tanks and mechanized transport (and bristling with guerrillas), which would ultimately halt the Japanese advance and moved the conflict into a long-term stalemate. Arguably, Chiang’s flood bought China enough time until the Allies began to converge on Tokyo after 1944.

However, even the Generalissimo did not feel strong enough to stand by his decision. On June 11, Chiang ordered news wires to report that a Japanese aerial attack had breached the dike—a narrative picked up by the Communists’ Xinhua Daily, as well as the Associated Press. The truth admitted by Wei Rulin, one of the commanders involved in the operation, after Chiang’s death in 1976.

Today, the flood is considered “the largest act of environmental warfare in history.” Historian Rana Mitter, in Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II 1937-1945, describes it as “one of the grossest acts of violence” of any government against its own people, suggesting that “a leader more humane than Chiang” would never have contemplated it. The deliberateness of the act, and lack of warning for the populace, also did not endear survivors to the Nationalist cause, a fact later used by the Communist forces to their advantage.

If causing mass tragedy, and then lying about it, was grudgingly accepted as a means to an end, the fact remains that anyone living in the floodplains of the Huanghe does so at great risk even today. While modern flood prevention, warning, and rescue and relief efforts have improved, “China’s sorrow” still remains a greater and more destructive force than even its worst human enemy.

Cover image from VCG