Tie dye pioneer Zhu Xinwei’s new book breathes new life in a traditional Chinese craft

Last summer, controversial judge Kris Wu of The Rap of China was hailed a fashion icon for bringing tie dye to China—since 2018, the bleaching aesthetic has become “one of the five biggest fashion trends,” according to the BBC.

It’s a little-known fact, though, that China actually has a long tie-dye history of its own, which is highlighted in a new book, Jiesi Chengwen (《解丝成文》) by Zhu Xinwei. A former China Academy of Art teacher, Zhu Xinwei was one of China’s earliest modern artists to use tie dye, holding an exhibition in the National Art Museum in 1989 which brought this ancient art form back to the modern world.

Archeological and historical records suggest that tie-dyeing clothes was already widespread in China during the Southern and Northern dynasties (420-589), 1,500 years ago.

Historically, Chinese tie dye was known as 缬 (xié), which the Tang dynasty (618-907)Buddhist Huilin Scripture defines as “tying the silk fabric and dyeing.” The Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) Notes to Zizhi Tongjian elaborates: “Xie is to twist the fabric and tie it with thread, then untie after dyeing. The tied part retains its original color, while the rest is dyed colorfully.”

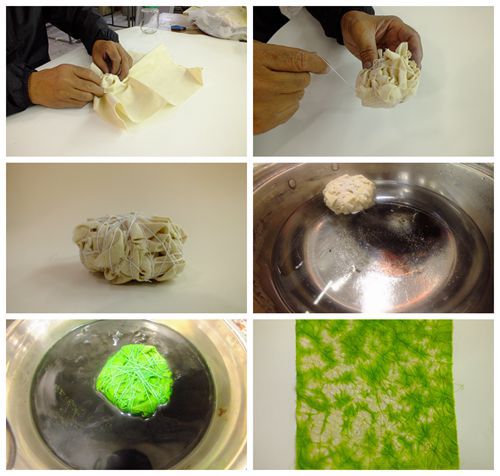

The “tying the silk fabric and dyeing” process is shown here

Despite this simple two-line summary, xie was a complicated process that demanded a great deal of manual work. After its “golden age” during the Tang, tie-dying was prohibited by the Song dynasty (960-1279) due to its extravagance, and became almost extinct except in some ethnic minority regions in the southwest of China.

Tie-dyeing is done by first drawing patterns on the fabric, then “resist-dyeing”: tying the fabric, sewing, splinting, and dyeing. The process can be repeated several times to achieve different effects, and the results vary, depending on the fabric, pattern, dye density, temperature, dyeing time, or which one of the over 100 possible resist-dyeing techniques was used. This means that each tie-dye product is unique, even if made by the same artist.

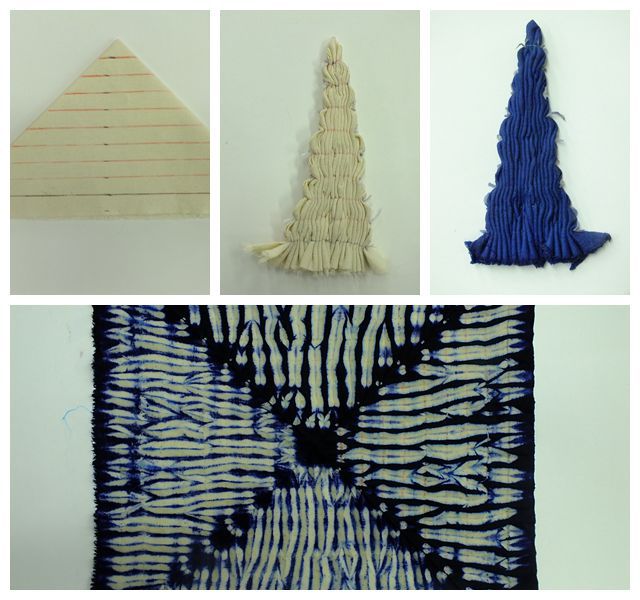

Sample sewing techniques of tie dye

The tie-dye techniques of Dali’s Bai ethnic group in Yunnan province, the Zigong of Sichuan province, and Nantong of Jiangsu province are the best known in China; the first two have been awarded “intangible cultural heritage” status on a national level, and the latter on a provincial one. In 1984, the tie-dye factories in Zhoucheng, Dali, employed nearly 5,000 locals and exported 80 percent of their products to over 10 countries and regions, including Japan, Britain, America, and Canada.

Traditional tie dye uses natural plant dyes, especially indigo from the plant isatidis. The effect is like a combination of Chinese ink and Western oil painting, albeit with more imaginative colors and styles. Some Song poets used the term “drunken tie dye” to describe the dreamy appearance.

Sample splinting technique of tie dye

Published by the Commercial Press, Jiesi Chengwen (《解丝成文》) offers readers a detailed history and explanations of tie-dye techniques, and illustrates Zhu’s 30-plus years’ experience with 200 of his unique patterns, along with instructions for creating your own tie-dye piece.

Several Zhu’s original patterns included in the book

And if that sounds like too much work, a handmade tie-dyed cotton kerchief is released with the book, offering another way to enjoy this seasonally appropriate ancient craft.

All images by Zhu Xinwei and The Commercial Press

This handmade kerchief is available on our online store