Are women really banned from the banquet table during Chinese New Year?

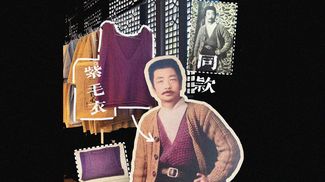

Public figures making sexist remarks are sadly commonplace in China today. One is internet entrepreneur Liu Huafang, who believes Chinese civilization may collapse if women are offered a place at the table—literally.

In a controversial blog post published on February 10, 2019, Liu defended a tradition of “banning” women from the dinner table at New Year banquets in some parts of China. Actress Cheng Lisha first drew public attention to the practice in 2017 after she took a visit to her husband’s ancestral village in Shandong province (Cheng, as a guest, was allowed at the table).

Subsequent media coverage portrays the custom as a primarily Shandong habit, though it has also been reported in Henan, Jiangxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, the Chaoshan region, and Northeastern China. Liu, who has Shandong ancestry, started his blog posts by rejecting the stereotype of his province as a hotbed of chauvinism.

Liu goes on, though, to praise Shandong for preserving the etiquette rites of its native philosophers, Confucius and Mozi, and says daughters-in-law should make room for their in-laws and elders if there is limited seating at family banquets (while saying nothing of sons’ and sons-in-law’s obligation to do the same): “Disregard of propriety and shame lead to cultural degeneration,” he writes. “As a daughter-in-law, shouldn’t you be helping your mother-in-law and sister-in-law cook? Or are we supposed to let daughters-in-law socialize and drink with the guests?”

Readers’ responses have been mostly negative: Top comments on Weibo cheekily congratulated Liu for “excellent slander of Shandong,” crowning it as “China’s top province for bare branches,” or single men unable to find women to marry.

An internet survey by Netease in 2019 suggests that the custom is already the wane: 57.5 percent of respondents said their families had no seating restrictions during Spring Festival. “I have heard of the custom, but have never seen it enforced,” Wang Qunhong, a 29-year-old woman who grew up in a village near Ji’an, central Jiangxi province, tells TWOC. “Personally, I never cook, so I sit at the table.”

Nevertheless, many women are de facto banned from the table due to their other feudal obligations. “China’s feudal culture says it’s the women’s job to cook, and the men to drink and entertain the guests, so women often have no chance to eat until the men are done,” says Wang.

Bai Hongtan, a 36-year-old rural communication scholar based in Liaocheng, Shandong, believes that the issue is often misrepresented in media. Bai is the author of “A PhD’s Homecoming: My Village Still Preserves the Custom of Not Letting Women Eat With the Guests,” a viral article published by Beijing Youth Daily during the Spring Festival of 2018.

He tells TWOC, though, that the headline, which attracted 5.5 million views, was sensationalized: “I wanted to focus on the broad gender divisions in my village…but many readers accused me of perpetuating myths about Shandong as a very backward place.”

Bai agrees it is traditional gender roles, rather than an explicit ban, that effectively bar women from taking part in the feast. “In my region, a woman wouldn’t actually be chased off if she sat down at the table,” he says.

“What’s actually at play are traditional divisions of labor in the village, which are imbalances inherited from the past. The idea of ‘women inside, men outside’ states that women should stay in the kitchen, while men can be out in public with the guests,” he explains. Other Spring Festival rituals, including calling on relatives and worshiping the ancestors, are also traditionally performed by the “male offspring” (男丁) of the family in Bai’s region, and by married women on rare occasions.

In his article, Bai wrote that when food was scarce in his childhood, women and children only ate at weddings and New Year banquets after the men and guests have finished. He even alleged that this was the basis of the custom that guests must only eat only one side of the fish, so as to save the other side for women and children to eat (along with the other leftovers) when they take their turn at the table.

“There was an interminable wait to eat the underside of the fish, because the men would drink for hours,” Bai wrote. “The taste of tobacco and liquor mixed in with the dishes is an inerasable memory from my childhood.”

Women and children may no longer have to eat leftovers, but do often sit at a separate table or even in a separate room. In Netease’s survey, only 5.8 percent of respondents said that women in their families did not eat at the table at all; but 35.8 percent said they ate apart from the main table.

The custom still has its defenders: Over 60 percent of Netease respondents were against or unsure about challenging traditional divisions at home. Actress Cheng recommended that guests “do as the Romans do” and respect the host’s customs. Commenters on a Douban thread justified the custom as a separation not based on gender, but a division of drinkers and non-drinkers; or argue that women and men discuss different topics at the table, and will feel more comfortable sitting with their own gender.

Bai believes China still has a long way to go toward improving the situation, as the public’s overall awareness of gender stereotyping is low. “Many people only consider the problem at the individual level, such as feeling bad that their mother have to cook so much, or that the smoking and drinking at the main table are so unpleasant for the women,” he says.

“Realizing the idea that women have be the ones to cook and watch the children, or that men will want to drink while women definitely will not, are related to a broader framework of gender discrimination—that’s a whole other level of consciousness.”