TWOC gets the scoop on the new 40 Years of Reform exhibition at the National Museum

It was a cold and unusually polluted day when TWOC arrived at the National Museum of China (NMC) on Tiananmen Square, so we were surprised to find a vast crowd of pensioners already bustling outside, with estimates of a half-hour wait just to enter.

Admittedly, the museum has been entirely refitted to accommodate China’s 40 Years of Opening Up and Reform, an exhibition advertised daily on CCTV, and visited by Xi Jinping himself. But the sheer ferocity of the Chinese grannies and grandpas, pushing past us in line, was still surprising.

The mandatory checks for one’s ID card or passport (with optional facial recognition), set up in makeshift white tents outside, were also slowing things down. (My passport reader worked surprisingly efficiently; my companion’s face, on the other hand, did not match up with his ID, causing a slight delay.)

The NMC refurbishment for the 40 Years exhibition was evident outside

The grand entrance was filled with groups on team-building exercises, wearing red and waving the Communist Party flag; families; couples on dates; and a substantial number of “lone rangers,” most of them elderly.

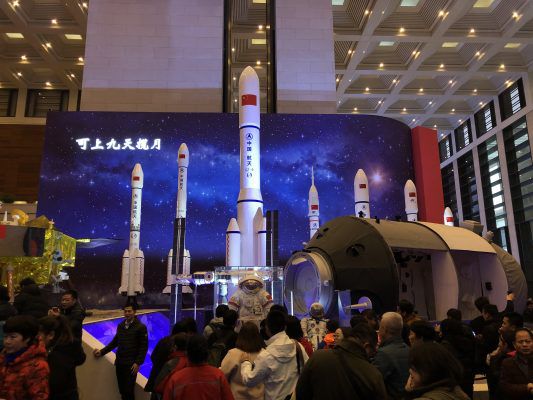

The NMC, the world’s third-largest museum (just after the Louvre and the St. Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum) can seem daunting even on a normal day. The massive scope of this exhibition, though, fit the space surprisingly well, thanks to its floor-to-ceiling video screens and life-size replicas of deep-sea diving vehicles, space crafts, and high-speed trains.

People thronged in the main hall to take photos with models of China’s rockets, space crafts, and astronauts’ space suits

While the target audience is clearly domestic (unless you are one of China’s foreign friends, with fluent Mandarin skills), the exhibition is largely image-based. Videos, photos, economic charts, models, and replicas make it relatively accessible to everyone. There are also a large number of interactive activities, from a robot that can draw caricatures to a simulation of a high-speed train cab; from a VR machine simulates a climb up one of the State Grid’s power lines, to screens that can display all the flights a person have ever taken with just one swipe of their identification card.

One display showed the changing products in Chinese homes over the last past decades, such as the “three big items,” typically purchased to seal a marriage, as well as a “Xiao Bawang” console (essentially a Famicom clone) that every child of the 1990s would have wanted; the military section was also a child’s dream, with dozens of model-size aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines, tanks, and missile launchers.

The military technology exhibition showed images of military exercises, as well as PLA humanitarian missions

A Xinhua video exhibition offered inspirational imagery of city and countryside from around China.

The museum also includes more traditional elements of a propaganda exhibition: there are halls full of oil paintings celebrating workers, soldiers, and farmers; and several of the rooms emphasize heavily politicized topics, such as national unity. There were also military-looking personnel present everywhere, surveying the crowd, as well as plainclothes officers (slightly more difficult to spot).

The main hall, normally housing politically themed oil paintings, outside a history of reform, with sections dedicated to each leader after Deng Xiaoping

Parents held toddlers on hips, recalling their childhood and how different it was. Seniors pored over descriptions of technologies, confusion and pride both visible on their face. “When I see all of the scientific innovations and experiments that the government is funding,” my friend commented,“I don’t feel so bad about China’s high tax rate. We are making important contributions to the world.”

People constantly posed for photographs, clogging up traffic. For those sufficiently moved, China Daily and CCTV had booths in which they could record their thoughts and emotions, presumably for later use as quotes. For many, this exhibition was clearly an emotional journey.

The author poses with a model of a high-speed train

Photography by the Emily Conrad