The subtle misogyny of subway ads

A morning commute from Tsinghua University to TWOC gets me up close with a lot of people: those who pat me down as I enter the station; push me around as I get into the car; peek over my shoulder to see what the laowai is looking at on his phone—and those who gaze at me from advertisements on the walls.

Chairman Mao said “women hold up half the sky.” Confucian philosopher Mencius, on the other hand, wrote, “To look upon compliance as their correct course is the rule for women.”

These unbalanced ideals of Chinese femininity—the equality espoused in the PRC constitution, versus the old custom of “elevating men, demeaning women” (男尊女卑)—are still reflected in adverts that bombard viewers from the sidewalk to the subways.

In China, as in the rest of the world, there is a long history of commercialized sexism that offers conflicting, subliminal messaging about the roles and perceptions of women. In July (and August, October, and November) of this year, there have been incidences of anti-women advertisements that courted controversy in China. In 2007, the problem was significant enough that Chinese Central Television decided to ban sexist and sexually suggestive advertisements from its channels, but only during summer vacation, in order to protect young viewers from their “negative influence.”

Most uproars are spurred by the blatantly misogynistic: an Audi ad comparing a new bride to a used car, an IKEA ad that shames single women. The advertisements in the subway are often less overt but are still symbols that communicate women’s place in a patriarchal society.

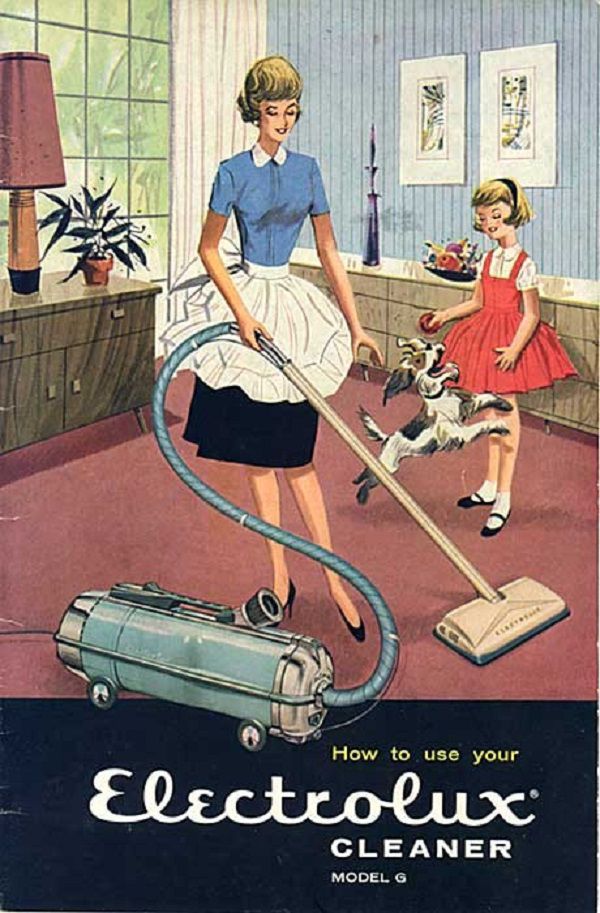

The magical (魔) time-traveling vacuum cleaner takes Liu Tao back to the 1960s

The above photo of Lexy’s advertisement in the Xizhimen subway station was replaced by ads for Oppo last week.

Lexy calls itself the “leader in high-end cleaning appliances,” which may very well be true, but on the feminist front, it is certainly far from pioneering.

The image of a woman behind a vacuum contributes to the traditional idea of women being relegated to the home. Many scholars have regarded the vacuum as a symbol of female oppression. Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique, once wrote: “Women of the world unite: You have nothing to lose but your vacuum cleaners!”

Similarly, Female Eunuch writer Germaine Greer has said, “I wanted to liberate women from the vacuum cleaner, not put them on the board of Hoover.”

This 1960’s, US advertisement is strikingly similar, down to the pose (Etsy)

This advertisement extends the connection between femininity and domesticity with the young child and dog, (unconsciously) plagiarizing the 1960s Electrolux Appliances ad that shows a child with a dog and a White woman vacuuming in heels, her arm outstretched in a way almost identical to the heeled woman in Lexy’s ad.

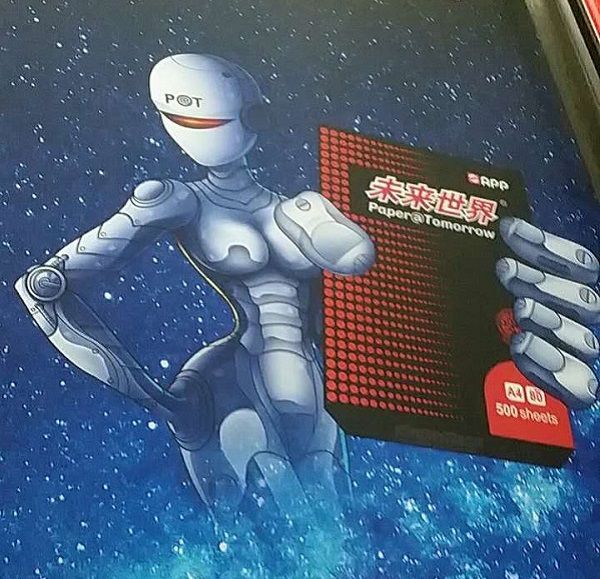

Meet P@T, Paper@Tomorrow’s full-figured robot mascot

Arriving at Chaoyangmen Station, there’s a sense of moving not only through the city but also time. Here, the robotic woman I encounter on the escalator looks like she’s been sent from the future, but the aesthetic suggests we’ve gone back to the 1950s.

It may seem silly to use a hypersexualized woman robot floating in a cluster of stars as an advertisement for a paper company, even one whose slogan is “future world” (未来世界). The connections between a well-endowed robot and printer paper becomes clearer, however, in the context of the robotics industry’s rocky relationship with gender.

Created in an industry dominated by men, robots’ looks and functions often reflect traditional gender stereotypes.

As the managing director of Silicon Valley Robotics Andrea Keay explains, “When all kiosk robots are female and all guard robots are male, we are patterning our stereotypes and our biases and perpetuating them.”

Appropriating the female figure for robots has been proven to have a positive effect on people’s attitudes towards these robots. In a small-scale study about gender and artificial intelligence at the University of Washington, one participant admitted that they feel more comfortable with female robots, because “the feminine form is typified as being weak or fragile in some form, but really inviting and more interactive. Whereas if it were a male robot and masculine design, then there’s a safety issue.’”

Perhaps it was associations of safety, not sex, that led to the creation of P@T, the Paper@Tomorrow robot? Regardless, the prevalence of traditionally feminine aesthetics in robots reflects current notions of femininity, and could even affect how we treat each other: What will society look like when its views on gender roles are informed by female-looking AI (or images of AI) filling the roles of assistance, service, and pleasure?

A 1954 poster on women joining the industrialization of the country, vs. today’s safety bulletins (chineseposters.net)

Subway ads featuring women aren’t completely misogynistic: One of the most prevalent underground images is an attractive female firefighter, used in fire safety bulletins. The decision to depict a woman in a traditionally male occupation recalls propaganda posters in the Cultural Revolution, which desexualized women (showing them with ruddy cheeks, shorter hair and less form-fitting clothes) and put them alongside men laboring in the countryside or on public works projects. The modern version, though, is somewhat more nubile.

With her stylish pantsuit, she may look like a Chinese Hillary Clinton, but presenting an air purifier, this ad’s aesthetics are just a small step up from a woman standing behind a vacuum.

There’s some sort of attempt at a happy medium between Confucianism and Maoism as I walk to the exit. Here is a woman wearing a pantsuit, often a symbol of female liberation and empowerment. However, with her left hand on her hip and her right arm outstretched, she presents an air purifier. Although suited, she is still associated with domesticity.

In this ad is perhaps a sort of summary of the struggle for gender equality in China: A woman in corporate dress rules the domestic sphere; she has the resources to buy fancy gadgets, but uses them to ensure the health of her family. As traditional and revolutionary ideals collide, it seems that women are supposed to embody every expectation—helped by ads that tell them how to act, be, and “have it all.”

In Chinese, there is an expression 蒙在鼓里. Literally, it means to be “kept within a drum.” Figuratively, it describes someone kept in the dark, uninformed. Fleeting through the darkness of the subway it is easy to be shrouded in ignorance.

But the ditie’s drum is more than a figurative darkness. Misogynistic messages in media do not only exist above ground or in obviously demeaning IKEA ads. They can be covert, easy to overlook, but ever-present: both underground (literally) and before us, hiding in plain sight.

Cover image from flicker.com