As another annual”Cashless Day” concludes, not everyone is enthused with mobile payment

A fresh series of promotions, launched by Alibaba and Tencent, form part of an ongoing drive to promote mobile-payment systems over cash, under the banner of a “cashless society”—a scenario welcomed by some, even as it raises concerns over privacy, big data, and the increasingly monopoly that private technology has over everyday lives.

At Tencent, August 8 was Cashless Day, with cash rebates for using WeChat Pay, Tencent’s mobile payment service, between August 1 and 7, valid for a one-off spending day. It also offered random discounts on WeChat payments, ranging between 5 RMB and 88 RMB.

Rival Alipay, currently the world’s largest mobile payment platform, meanwhile decided to expand the celebrations into a week. Known as “Cashless City Week”(无现金城市周), from August 1 to 8, Alipay offered rebates of up to 4,888 RMB for using its mobile app to make payments, including the chance to share 18.888 kg of gold with other users. For the first three days, residents in Hangzhou and Wuhan, two Chinese cities identified by Alipay as models for their cashless society notion, took buses free of charge by scanning the app up to 12 times.

Such efforts represent just a small part of the efforts Alipay and Tencent are making to create a cashless society.

As early as February, Alipay announced their plan to create a “Cashless Nation” in five years. It’s an ambitious goal, but early signs have been promising. On July 31, Tencent, in cooperation with marketing research firm Ipsos, released a survey in which 14 percent of Chinese respondents stated they no longer carry cash when they go out, and 26 percent took less than 100 RMB with them every day. Over 84 percent said that, if they have their smartphones on hand, they’d happily go without cash.

A survey conducted by Sina Weibo this year also showed the cashless lifestyle on the rise. Among 40,000 respondents, more than 70 percent believed that carrying cash was not a necessity; 11 percent believe we are “already living in a cashless society.”

Urban planners have jumped aboard this trend. In June, 25 universities in Tianjin jointly piloted the concept of “cash-free campuses,” allowing a total of 700,000 college students to pay tuition fees and other expenses on campus by app.

In June, Hangzhou introduced the “facial scan” identification system, allowing hospital patients to convert their biometrics into QR codes, which will serve as IDs for receiving medical treatments and making payments. In February 2016, the Guangzhou Women and Children Medical Center joined with Alipay to launch a “Payment after Treatment” system, making it possible for patients who have a Sesame Credit score of 650 and above to get medical exams and prescriptions directly, and pay after treatment.

For a more extreme example, in April, People’s Daily reported a beggar in Jinan, Shandong province, using a QR code to ask passersby for money. Residents living around the site told the paper that begging via QR code was now prevalent among local panhandlers.

But the increasing popularity of mobile payment is also cause for some concern. Reports that certain merchants are no longer accepting cash payments, such as a Shanghai seafood market investigated by Worker’s Daily this week, has triggered debate in Chinese media about whether this marginalizes people who don’t use online payments—or just plain illegal.

The Law of the People’s Bank of China states that stores in China cannot refuse to take payments in renminbi, but news outlets such as Beijing News and CBN have asked legal experts to debate whether this refers only to the currency or physical bills and coins. No conclusions have been reached yet.

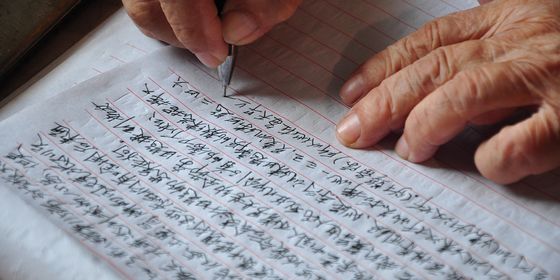

According to Worker’s Daily, the bulk of the customers who have complained about the Shanghai market belong in the middle-aged to elderly demographic. A Mr. Jiang tells the paper that he had been lured by the freshness of the store’s seafood and piled his basket high with succulent morsels, only to be handed a bewildering list of instructions at check-out: “They said to download their app, then register your Alipay account, and only then can we pay,” he complained. “I’m 68, and don’t use my mobile phone all the time like young people, isn’t this just discrimination against middle-aged and elderly consumers?”

There are others who distrust being at the mercy of all-powerful but anonymous systems, and privacy is a concern. Mobile pay opens up ever-increasing avenues where your account information, phone number, purchasing habits, and other personal data could be stolen with every mundane transaction. But so far, it seems that the convenience of mobile payment is trumping other concerns: last year, WeChat reported that more than 100 million users and 700,000 stores around the country participated Cashless Day promotions on August 8, 2016, and the individual reports that have trickled in from around the country suggest similar patterns this year. With Big Data climbing into the driving seat, as Big Brother gives directions, for many, it’s a case of destination unknown.