Grinding through China’s hip hop scene

Welcome to Dada, a grungy club in the old-town heart of Beijing, most often known as a late night jaunt for expats looking for something to jump around to in the wee hours bordering on sunrise. Tonight, though, things are different; it’s not quite midnight, but it’s already time for round three. The lights are dim. Sweat flows, and the crowd jostles, pushing and shoving to get to the front for an unobstructed view of the spotlit stage. At the back of the room, three producers sit at their computers, MPC-2500s lighting their faces with blue and red flashing lights reminiscent of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Among them is Jeff Liang, an LA-native who lives and works in Beijing as a musician and producer, known to many by his stage name SoulSpeak. Liang, from his workstation, flicks a switch, sending his mix to the monitors, a stinging surge of pre-recorded piano and guitar licks he’s played himself, combined with loops he’s appropriated from a Bobby “Blue” Bland album.

On stage, MC Dawei, a thin man with a wispy mustache protruding from under his black fedora steps up to the stage, grabbing the microphone off the stand. You can’t see his eyes from under the hat, and his oversized black suit gives the impression that he’s shying away from the mic; as soon as the groove kicks in, though, he’s anything but. The first beats of Liang’s mix explode from the speakers, the bass drum pulsing like a magnified heart beat, and all of a sudden the crowd’s bumping like it’s 1995.

Hip hop, like many other imported American cultural art forms, is slowly bumping and grinding it’s way through China, propagated by the internet and a keen interest in localizing the aggressive aesthetic of this uniquely American art form.

“Hip hop culture in general has been shifting,” Liang says, from his walkup in east Chaoyang. Liang, a glasses-faced Taiwanese-American with a clean shaven head, smokes a cigarette as he lords over his kingdom, an ever growing pile of mixers, keyboards, wires and synthesizers. “It’s [the shift] reflected in China, but it’s, maybe, a step slower than in other places.” Liang is speaking about global trends in hip hop, the change from the socially-conscious hardcore, aggressive rhymes and loop-based, drum machine tracks of NWA and Grandmaster Flash to what he considers watered-down hip hop: the likes of trap and bass music like Migos or Drake. “They simply have better music production back home,” he says. “Because if you really think about it, the hip hop scene here is really small—there’s just not that many people doing it, and that’s why it seems not as good.”

Improving that production element is Liang’s job: to create the grooves over which the MC’s can flow or rap. MC’s like Dawei, Xiao Laohu, and their counterparts in Chengdu and Chongqing have to lean on producers like Liang to create music that appeals to their tastes. As an LA-born artist, Liang has the advantage, having been immersed in American hip hop culture since he was young.

“I’ve been collecting drums from vinyl, from old records, since I was 15—and I have a huge pile of drums. I also record environmental noises as percussion that I can turn into pads, strings, or synths. A lot of times it depends what the goal of the project is; if I’m just working on beats, then you know I’ll start from a groove or a sound that I hear, or maybe a progression—there’s no real set process.”

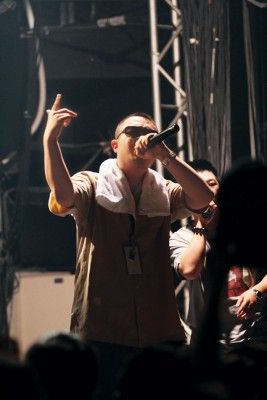

MC Webber performing after the launch of his album

Liang is also keen for more unorthodox approaches to vary the development of his projects: “I also like to use visuals. Sometimes I’ll just put on a movie, like Bladerunner, like a scene that I like, and so sometimes the changes are moving with the visuals. So I don’t necessarily use the same structures I’m used to. For hip hop, I’m mostly just thinking about the groove, just the movement of the bass and drums and how everything fits on top.”

Being able to create for the artist on stage is what sets Liang apart from many of his cohorts. His beats draw on traditional hip hop elements that make it easy to “flow” over but also allow for specific nuances of the Chinese language to find their way into the music. Liang specifically produces for several artists who are generally considered fringe artists for their lyrical content or style.

One of them is MC Dawei, a Beijing native who is a martial arts, literature, and history buff. The visuals that accompany Dawei’s performances often push the envelope in both aesthetic and content. “Dawei is trying to push the envelope with history and using that in his lyrics.” It’s very edgy stuff; you’re just as be likely to hear him drop a reference to Lu Xun as you would about modern social issues. There’s something in his aggression, and Liang’s heavy-hitting drum tracks are reminiscent of the Wu Tang Clan, which is, perhaps another bizarre layer atop this strange mix of cultures. Dawei, a veteran champion of the freestyle festivals that used to rock Beijing’s underground rock halls and small clubs like D22 and Yu Gong Yi Shan, is one of China’s more edgy rap artists. His content walks a fine line between edgy and outright dangerous, especially for a Beijing-based performer—with increasing numbers of drug raids on performance venues known for hosting counterculture or underground music in the Beijing area. Many of the hip hop community have come under closer scrutiny for their involvement in these scenes. For many, this is seen as an attempt to rein in the content of a culture that might be excessively fringe in a materialistic or political nature.

Click here for the the conclusion.

“The Rap Battle for China” is a story from our newest issue, “Family”. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.