The conclusion to being on top of the world

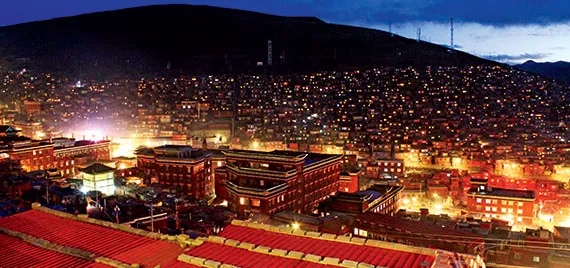

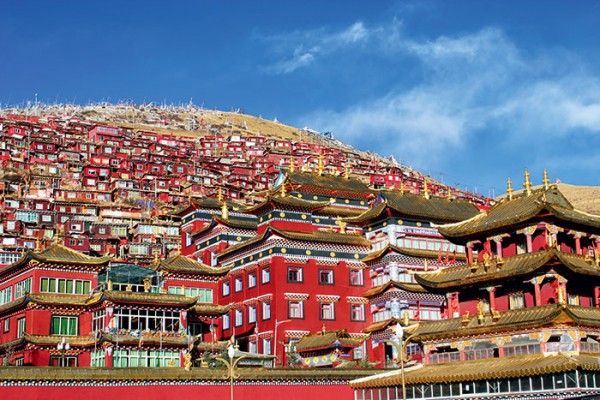

Founded in 1980, the Buddhist Academy today is home to nearly 10,000 monks both male and female. There is no limit to how long they can study there. Their resting quarters are separated by gender, as are their classes, which are for the most part taught in Tibetan. Still, courses in standard Mandarin are offered, and the academy subsequently attracts some monks from non-Tibetan regions of China as well. The distinction is easy to make: the robes of the academy’s monks are red; those of other affiliations are not.

Come nightfall, the temperature dropped significantly and I found myself with two other Chinese tourists and a monk of the academy—a friend of a friend of a friend—in his leisure quarters. The decoration was of a surprisingly high quality: thickly carpeted floors, light wooden panel walls, a low ceiling, and a wild amount of books. Two thangkas and a portrait of two smiling monks were hung on the wall. The room was cozy, and after running a small heater for perhaps 15 minutes he shut it off and the room kept its temperature throughout the night. The monk said he didn’t want the room’s temperature to be too different from the outdoors, as that would be unhealthy.

He cooked three times and attended class twice every day. Over some tea he was eager to talk about a swath of topics, from meditation to yin and yang to the various monotonies of everyday life. He said their classes were free. The academy would occasionally pay them, but usually they were just given food or goods. I asked him when he decided to become a monk. He took a sip of tea and said, “Probably by the time I was seven.”

After a while the monk pulled out an iPad and began to show us some pictures of various monastic enclaves from his travels throughout the world. Some were candids, and in some he posed with a bright umbrella under the Tibetan sun—standing up, lying down, sometimes alone, and sometimes in a group, but invariably smiling. Looking at these photographs, it began to dawn on me why a person should visit the academy at Seda: Because it is a peek into an entirely different take on life. In the academy, life is disciplined, sexless, and aspiring to some higher ideal. Sinologist Livia Kohn characterized the monastic lifestyle as existing in a “liminal” space—created in the image of heaven but bound to earth, a rejection of secular life but of the same realm.

Whatever the case, as I looked at the photographs I began to feel it was a lifestyle I could neither say was better nor worse than my own—such comparisons are irrelevant because it is not something I can fully understand. I have not spent long periods in so remote a place. When I was a child I looked up to athletes and astronauts. Perhaps the first fact I can alter, but the second I cannot. My point is that my secular experience with life is different, but looking at the photographs I felt that, while the two are impossible to compare, perhaps both lifestyles have just as equal a chance to be either fulfilling or not. The inputs are different and the scoreboard not the same—perhaps this is why you should go to Seda: to glimpse into a different experience with life; to find a different angle from which to evaluate your own.glimpse into a different experience with life; to find a different angle from which to evaluate your own.

Situated on the southeast of the Tibetan Plateau, Seda is an oasis of both culture and amenities before the long march to the Tibetan Autonomous Region

In the mornings you can meet with a “Living Buddha” in his house. After a short period involving chanting and donations, the Living Buddha answered some questions. An glimpse glimpse into a different experience with life; to find a different angle from which to evaluate your own.

In the mornings you can meet with a “Living Buddha” in his house. After a short period involving chanting and donations, the Living Buddha answered some questions. An Englishman lives at the academy in six-month stints, and if foreigners are there he comes down to the residence and provides translation into English. One such question is the translation of “Living Buddha” itself. While Chinese to English renders such a translation optimal, from Tibetan to English produces some different results, I’ve been told. Perhaps “Reincarnated Buddha” is a more fitting translation.

At any rate, the Living Buddha, if you will, was friendly and with a mild cough. Some of the questions he answered in great detail. “How can I control my frustration better?” asked a Japanese tourist. “Concentrate on a triangle below your navel, let it emanate out…” He instructed her to consult a specific chapter of a book, which I did not write down. Some questions he answered concisely: “How can we improve the world, have peace, and so?” “First you must perfect yourself, then you can perfect the world.”

After the question session ended, everyone gathered into little groups and discussed the event. A lady went up to the Living Buddha to ask a question in private. The Japanese girl commented to a monk and the translator excitedly on his advice: “So, like, run to the top of the mountain and scream!”

You can also see sky burials at the academy. I was told that while other Tibetan monasteries and academies use different methods, at Larong Wuming Buddhist Academy this is the only form of funeral in use. Essentially, atop a nearby mountain the bodies of the deceased are prepared, and then throngs of vultures consume them. A driver from the academy explained that there is a fixed price of 60 RMB per car to get to the sky burial, but I managed to hail a motorcycle for less. I arrived as the bodies were being prepared and the birds waited patiently. Then their time for waiting came to a conclusion and they feasted, and carried the dead into the sky. I found it a poetic notion in some ways. The smell was terrible.

The last day was aimless. After buying tickets we returned to wander around the academy and bought some fruits for the trip back. I stopped back by the monk’s place and he showed me some English characters he had written earlier. They were beautiful. The last bus back to Seda left at five, so I spent the evening there.

“The Path to Seda” is a story from our newest issue, “Family”. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.