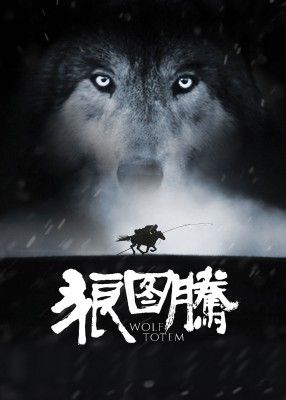

Visually stunning movie, but lacking in other departments

When Jiang Rong’s (姜戎) novel Wolf Totem was published in 2004, it saw huge sales, won critical acclaim (the inaugural Man Asia Literary Prize), achieved resonance with the public, and was generally seen as a tour de force. Sadly, the 2015 film adaptation is unlikely to do the same, the movie often feeling as bereft and empty as the Inner Mongolian grasslands on which it was shot; the film is a sheep in wolf’s clothing, if you will forgive strained lupine metaphors. The film follows the journey of Chen Zhen (Feng Shaofeng) and his friend Yang Ke (Shawn Dou) at the start of the Cultural Revolution when they are posted from Beijing to Inner Mongolia to help teach Mandarin to nomadic herdsmen. Along the way our young protagonists learn many things, among them: city boys will never truly understand rural life (and might be better off in Beijing); political apparatchiks are largely bothersome and don’t know what they are doing (especially when it comes to dealing with shepherds); and, most importantly, don’t mess with the wolves, for they are spiritual animals.

Fundamentally, the film aims at penetrating two overlapping themes: firstly, that city types, and by the extension the government, should be wary of imposing their will upon the fountain of knowledge that are indigenous ethnic populations, in this case wise and noble herdsmen who have existed for centuries without interference from outsiders. Secondly, do not toy with the delicate balance of nature, specifically that between grass, gazelle, sheep, man, and wolf, as this will inevitably cause intense ecological disaster. Of course both of these themes are immensely laudable, but when such ideas are delivered without conviction, meaning, or the pre-requisite skill, instead seemingly just for the sake of it, well, nobody listens and it all ends badly—this is largely the case with Wolf Totem.

Chen Zhen:

Did the awe that the Mongolian wolf inspired come from a cult deeply entrenched in man’s brain since time immemorial? My heart filled with gratitude for the secret forces that came to my rescue. I had the feeling that I’d started to open the door on the spiritual world of the grassland people.

Yīn cǎoyuánláng suǒ chǎnshēng de kǒngjù yǔ jìngwèi, shìbushi cóng yuánshǐ shíqī qǐ, jiùshì rénmen xīnlíng zhōng suǒ chóngbài de túténg. Wǒ duì zhè zhǒng shénmì de lìliàng jǐ yǔ wǒ de bāngzhù mǎnhuái gǎnjī. Wǒ yǒu zhǒng gánjué, wǒ yǐjīng tuīkāi le tōngwǎng cǎoyuán rénmín jīngshén shìjiè de nà shàn mén.

因草原狼所产生的恐惧与敬畏,是不是从原始时期起,就是人们心灵中所崇拜的图腾。我对这种神秘的力量给予我的帮助满怀感激。我有种感觉,我已经推开了通往草原人民精神世界的那扇门。

The choice of French director Jean-Jacques Annaud was in many ways an odd choice from the outset. His last China film, Seven Years in Tibet was banned in China and, as one would imagine, widely criticized by the authorities. However, somewhat remarkably, it seems he has been forgiven. Annaud has apologized for any upset feelings he caused anyone with his earlier film. And Wolf Totem, as with the book, had no problems with censors at all, which, when considering the sensitive themes it touches on, is a bit strange. The more cynical among us could be inclined to ask if this is why the film, unlike the wolves shown in it, lacks bite.

All this is not to say that parts of the film are not magnificent. Without a shadow of a doubt, it is a visually stunning film; the sweeping score is affectingly emotional and you see superb shot after superb shot of the Inner Mongolian grasslands, in snow, in spring, and in summer. It is all rather epic, which is all just as well as it is one of those films where you feel nothing would be lost if the voices, or more specifically the subtitles, were turned off. Such is the confusion of the plot.

Other than the broad and obvious “leave those wolves alone” and “don’t mess with the indigenous population” message, the film lacks direction and any sense of narrative cohesion. Often it is not clear if the “bad guys” are the party officials, the teachers from Beijing, or even the wolves themselves, which would all be well and good if this was a delicate study in ambiguity but it isn’t. Instead it feels like a film that can’t quite find its identity. Even the almost-love story, always a useful device to hold an iffy plot together, feels bolted on at the last minute, which is a pity as Ankhynam Ragchaa turns in, perhaps, the only mesmerizing performance of the film, as Gasma, the Mongolian widowed early in the film, her affections slowly moving toward Chen. She deserved more screen time.

For many, the wolf has long been the archetypal “spirit animal”, whatever that means, and for those that buy into such mythology, it is easy to assume the premise of the film is on to a bit of a winner, but, again, this is a trope dealt with in clunky fashion. The script’s attempt to form a timeless bond between wolves and Mongolian herdsmen is strained at best, as when the film’s wise old man—let’s call him the Mr. Miyagi figure—tells Chen, “Life is about choosing the right moment, wolves and Mongols understand that.” Attempts to inextricably link the fate of the Mongol people with wolves become increasingly spurious, to the point where at one point, perhaps the greatest Mongol of them all is enlisted, “Genghis Khan was a master of war; he learned what he knew of war by studying wolves.” Perhaps, such words should not be taken literally and instead read as metaphor, but it is difficult when they come off as parody rather than anything meaningful. And all this isn’t helped by the fact that it has left more than a few Mongolians unimpressed.

“Zoetrope: Wolf Totem” is a story from our newest issue, “Mental Health”. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.