The search for Chinese tattoo style in a crowded industry

“You can see,” says Curt Li who manages the He Tattoo in Beijing’s Sanlitun district as he lifts up his shirt. “My dragon is not a Chinese dragon. It has a human eye, right? So, it’s not a kind dragon, it’s an evil dragon…But, basically, I wanted a dragon, and at that time I didn’t know dragons should have a circular eye.”

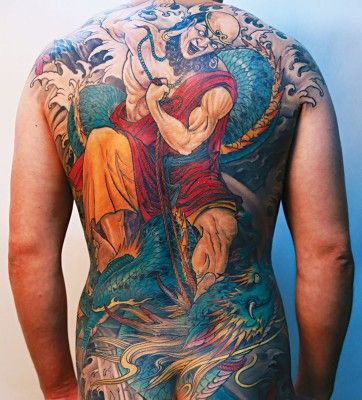

Curt, a Beijing native, runs a staff of five talented artists, each with their own specialty, be it photo-realism or Asian traditional. With years now in the mainstream, Chinese tattooing is settling in for a successful future in human canvases, with experts rising from every field, from American traditional to the ever-popular Japanese style. Of course, in true fighting spirit, the Japanese designs are, somewhat, Chinese.

“The Japanese style actually comes from Chinese style,” Curt says. “Thousands of years ago, the style started [in Japan] from Chinese-style art. And now, we learn from them.” While the styles of Japanese and Asian traditional tattoos are extremely strict—right down to the chrysanthemum leaf—most who walk into Curt’s shop are less interested in the traditions and styles of tattooing than just getting some ink, be it sexy or scary.

Indeed, while tattoos have been in China for quite some time, modernity has ended much of the stigma that used to be attached to tattoos in the Middle Kingdom. One door down from He Tattoo, there’s New Tattoo, where Chen Jie, a woman in a largely male dominated profession, has inked her way to a fine reputation over her 11 years of tattooing.

“I like the Chinese style,” says Chen, “but I want my own style. So, I combine my style with Chinese.” Chen is keen to show off the work of her colleagues on their Instagram, NEWTATTOO, where interested customers can check on their potential artist’s skills and expertise. Chen thinks the tattoo industry in China has nowhere to go but up: “In China it will get more popular, and in five to ten years, it will get better and better.”

“There are more than 40 shops in this part of Beijing,” Curt points out. What was once a niche industry has turned fiercely competitive, a world where reputation is important and mistakes are as permanent as the ink in the skin.

In just a few short years, tattoos have gone from taboo to common to a full-blown industry. The Shanghai Tattoo Festival, for example, kicked off in early October at the Shanghai Everbright Convention & Exhibition Center, 60,000 square feet of tattoo heaven with 20,000 eager patrons and enthusiasts. “It’s a kind of starting off point for the tattoo industry [in China],” says Fu Hailin an established tattooist with the Shanghai Tattoo Convention. “Someone has to take that difficult first step…We see an opportunity and a demand to carry forward Chinese culture; as to whether or not it makes money is not important right now.”

In just a few short years, tattoos have gone from taboo to common to a full-blown industry. The Shanghai Tattoo Festival, for example, kicked off in early October at the Shanghai Everbright Convention & Exhibition Center, 60,000 square feet of tattoo heaven with 20,000 eager patrons and enthusiasts. “It’s a kind of starting off point for the tattoo industry [in China],” says Fu Hailin an established tattooist with the Shanghai Tattoo Convention. “Someone has to take that difficult first step…We see an opportunity and a demand to carry forward Chinese culture; as to whether or not it makes money is not important right now.”

Conventions like these have been going on for years and they’re a great place for new artists to show off their talent. The Shanghai Tattoo Convention will host Chinese talent like Yue Heng, Yang Zhou, and Duze Wu—not to mention the talents of New York tattoo savant Paul Booth and equally talented artists from around the globe.

Just a few weeks later, in Qingxiu in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, another convention will kick off at the Nanning International Convention Center. A bevy of reporters will be looking at contest winners from a crop of some of the best tattoo artists in Asia for everything from Best New Artist to Best Sleeve Award. “We’ll be doing tattoos,” says Huang Jiayu, an old school style artist from the convention. “Maybe more than 200 artists.”

So, it’s fair to say that tattooing in China is well and truly off the ground. But, to the tattoo masters around the country, there’s more to ink than cash.

Ink as Art

Jeanne runs a boutique tattoo parlor in Beijing’s hip Gulou area, lit with a bluish florescent light, and while she’s happy to see the tattoo industry get bigger and the art form more commonplace, she wants to see it get better.

“At this level, we have a lot in the market. We need some good tattoo artists who can be creative and give the customer what they really want,” Jeanne says. “To be a tattoo artist, you have to spend a lot of time on the table. You have to decide you want to do it. If you want to tattoo just to make money, it is easy…just give people whatever they point at. You don’t create anything. You just take something from the internet. That’s just a job.”

Jeanne is known for taking a hard line with her customer’s ideas; after all, a tattoo artist can’t have sub-par work out there just because a patron has bad taste. Unlike painters, tattoo artists can’t hide bad canvases behind the sofa; their canvases walk and talk.

“I try to open customers’ minds and give them more choices. Most people want a traditional Asian tattoo. I ask why,” Jeanne says. “I try to understand why they want the tattoo that they want. If you want a dragon, why do you want a dragon?”

Tattooing, at its heart, is an art form. Jeanne has a firm grounding in art, having studied at the Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, but her background in tattooing goes back much further. “My mom, she taught me my first tattooing technique in the 90s. I actually started in 1997. My mom taught me how to do permanent makeup tattoos–eyeliner, all that girly kind of stuff–because she owned a salon.”

Jeanne has been tattooing for 17 years now, but like many other art-students-cum-tattooist, it was a bit of a meandering road. “I’ve been doing this since I got out of school. I started in France with special effects makeup, you know, like for horror movies. I did so much of this kind of thing. I did fashion designing. I think tattooing is closest to fashion design. It’s like clothes for your skin.”

For Jeanne, the relationship between tattooist and canvas must be a close one. “Tattoos are decoration for your body. Why do you wear nice clothes? You do it to make your body look nice. You want meaning; you don’t want a name, or title, or logo, or whatever,” Jeanne says. “The tattoo is not like a sticker you can just put on your body. It has to follow the shape of the body or body part.”

For Jeanne, the relationship between tattooist and canvas must be a close one. “Tattoos are decoration for your body. Why do you wear nice clothes? You do it to make your body look nice. You want meaning; you don’t want a name, or title, or logo, or whatever,” Jeanne says. “The tattoo is not like a sticker you can just put on your body. It has to follow the shape of the body or body part.”

With budding artists practicing on living works of art, perhaps the greatest test of talent, as well as test of relationship between artist and customer, comes when tattoos go wrong: cover ups.

Curt from He Tattoo says, “In small cities, it is not very good. In the rural areas, they don’t even know how to draw a picture, how to protect the skin, how to make color. We get very, very, very many cover ups.” Curt pulls out a picture of a deep black, poorly drawn tribal tattoo on a chest “Mission impossible. There’s some very bad work out there.” But, one of Curt’s artists was able to turn that 90s-era mistake into a raven with splashes of ink-drop color. “In the Chinese tattoo market, in the future, ten or 15 years, we’ll be calling the tattoo market the cover up market.” Chen Jie tacitly agrees, claiming that more than ten percent of her customers are after cover ups.

“If I do only Chinese customers, I do a lot of cover ups…When the Chinese want to do a tattoo, they want meaning in it. Some people just want their names. After 20 years, you want your name? That’s important to you? Your girlfriend’s name? Why?” Jeanne says. “Most Chinese, they don’t care. The Chinese mianzi, the face thing, a lot of Chinese just care if the artist is expensive or famous.”

However, bad tattoos and the tattoo artists who fix them aren’t born in a vacuum. The tattoo industry in China, as it is everywhere else, is a matter of master and student. Unlike many other professions in the art world and beyond, tattooing requires an apprenticeship, and whether an artist wants to be at the top of their game or just wants a shop where people can pick-and-stick, every artist needs a master.

Eleven years ago, tattoos were not as prevalent as they are now and Chen had to learn her art form on the fly, a process that has happily ended in excellent work. “I didn’t study in a school. I followed my master for…one year, but I learned painting and drawing. Tattoo learning was just by chance.”

Jeanne is currently open to having another apprentice, but previous experience has left her wary. “Whatever they do, [customers] are going to come back to me to cover it up,” Jeanne says. “A customer once came to me to cover something that they got in [my shop]!…You could see someone who didn’t know, who didn’t give a shit.”

Taking on an apprentice can be a potentially dangerous business decision. “Apprentices don’t have the experience to look at their work in two or three years. If you’re really a professional, you should know what your tattoo is going to look like when time passes. Small tattoos become like a [blob],” Jeanne says, adding that she is keen to find an apprentice who takes the profession seriously. “Man, woman, whoever can really show me their drawing and passion. You need the balls, the heart, and the passion. If I find a really good apprentice, I want to teach them everything I know, because I want my apprentice to be better than me.”

Getting Stuck

China’s big cities host an impressive list of A-list artists, with tattoo studios featuring wall art and even live animals–putting on at least the facade of a hip, happening subculture. More and more shops are popping up around China in smaller and smaller cities with better and better artists.

However, the art of ink-in-skin in China didn’t begin with the advent of the modern tattoo parlor. Some of the earliest examples of tattooing come from around the 4th century BCE, where the ancient barbarians of the West were depicted in the Book of Rites (《礼记》) as having tattooed bodies and unbound hair. Indeed, fans of Chinese literature might have noticed that the great Water Margin tome features criminals with face tattoos; however, information on tattoos of this period suggest that they were something of which to be ashamed–something barbaric, a defacement of the body and the mark of a criminal.

There is definitely some evidence in people of the West bringing tattoos to what is now modern day China, not least of which are the Chinese mummies of the Tarim Basin. They’re not what you would expect from ancient Chinese barbarians, and while the tattoos are certainly worth comment, most point out the fact that these ancient Chinese, found in Xinjiang, had red hair and deep set eyes.

There is definitely some evidence in people of the West bringing tattoos to what is now modern day China, not least of which are the Chinese mummies of the Tarim Basin. They’re not what you would expect from ancient Chinese barbarians, and while the tattoos are certainly worth comment, most point out the fact that these ancient Chinese, found in Xinjiang, had red hair and deep set eyes.

That said, not all tattoos came via the Silk Road; some styles are indigenous. Famously, the Dulong ethnic group, around the Dulong River in Yunnan Province, tattoo their women. It is said to come from a time when enemy tribes would invade and steal the tribe’s women for slaves in the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644), so marking their females’ faces (reportedly sometimes to imitate a male mustache) became a way of making their women less desirable. The rite was and perhaps still is performed using a combination of a thorn, a stick, and sooty water. The Dai people as well are famous for their tattoos, featuring much more complex designs than the Dulong people–from dragons to tigers–and are inked in with black plant juice. Children are first tattooed around the ages of five and six and again as a rite of passage during puberty. The designs are extremely delicate considering the elementary nature of the process.

The place where tattooing was most endemic in ancient China was an area of Hainan, home to the Li people. Their tattoos were not confined to the face; they began with the neck, moved to the face, and then went on to cover the legs and arms. Men usually had three small circle tattoos on their wrists (for medicinal purposes), but the women were covered in tribal designs of thick lines on the hands, arms, feet, legs, and face. While they may not be an example of the most technically proficient tattoos of ancient China, they are a testament to a time when this simple art of inking was an indelible cultural practice. The government certainly seems to think so, trotting out tattooed Li women–some in their 70s and 80s–to be admired at the 2012 Shanghai Expo.

While China may have gotten a late start in recent years on the art of tattooing, it’s not as late as you might think. “If you look at really famous tattoo artists, even traditional old school tattoo artists in Europe, it really started to be [recognized] as art and as an industry just like 20 or 30 years ago, so China is just ten years behind, maybe. So, the best tattooists are still really young,” says Jeanne.

China’s homegrown brand of talent is growing every year: from Jimmy Ho who was recently profiled by Vice and has been tattooing in Hong Kong for over half a century to the needlework of Zhou Danting, called China’s first lady of tattoo, by CNN.

But there are areas where China falls behind, mostly because the customers just aren’t interested. New school style is cartoony, a sort of nostalgic, bubbly, big-eyed, brightly-colored bit of animation on the body born from the 1980s in the West, but this sort of thing just isn’t catching on in China. “New school is something we are not really seeing in China. There’s just no history of the imagery here,” Jeanne says. “In the 80s, when America and Europe were into animation, we had comedies on the TV…How could you expect the Chinese to care?” In response to this, Jeanne believes, the best solution is more cooperation with the outside world and a broadening of Chinese horizons.

She is taking this responsibility seriously and brings regular experts from around the world into her shop to show Chinese patrons how different styles can be done well. “I try to invite different European tattoo artists, maybe one each month, but not in winter,” she says frowning at the thought of Beijing’s impending cold. “They won’t get a good impression in winter.”

And, while the Chinese tattoo industry is not exactly in its infancy, it’s certainly not as grown up as it might be. Artists and customers alike need to educate themselves, particularly when it comes to hygiene. Dangers don’t often pop up in the big, fancy Beijing and Shanghai parlors, but customers should still be wary of who inks them and how. “For the rich, if you’re famous or expensive, they don’t look if you’re clean or not clean. They just want expensive stuff. They don’t care if you’re tattooing them with dog blood,” Jeanne says. “Poor people, they just want to know how much. If it’s cheap, then they say, ‘Okay you can tattoo me with dog blood if you want.’”

China doesn’t have a constant in-and-out of new skin found in places like Hong Kong. Successes spread slowly and mistakes last forever; but that may just be the atmosphere needed to breed brilliant tattoo artists. “You see, when you go to Thailand, you have a tattoo shop on every corner, every two or three meters,” Jeanne says. “I think China will, in the big cities, become more like Bangkok. When you start to have that many shops, people will start to look for quality. We’re not tourists, we live here.”

“The Middle Ink-dom” is a story from our newest issue, “Mental Health”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.