China’s single women struggle for the right to have kids

“I’m getting old and don’t enjoy noisy bars like I used to,” says Mary, 36, who works as a deputy marketing director at a German company in Beijing. Mary isn’t her real name, but her German bosses can’t pronounce her Chinese name anyway. Mary was once the leader of a friendly “no-marriage clique”, absorbing new members and telling them to never worry about settling down, that singlehood is freedom.

However, now that she wants to have children, the official policies on this freedom are taking their toll. For Mary and the thousands like her, the system is not kind to the single.

“When a woman gets old, naturally, she wants to be a mother,” Mary tentatively admitted to her friends. Surprisingly, several nodded in agreement. Despite the concerns of wondering whether or not she is too old, Mary also worries about her health—what with her drinking habits and exhausting work hours. Her parents, upset by her celibacy claims, suggest she should register on a dating website.

However, Mary, like many others, was inspired by another Chinese woman: Xu Jinglei, 41, whose experience in fertility has given hope to many women. Xu said in an interview that egg-freezing technology was the only way she could justify her decision to not have a baby right away.

The technology is not commonly known or used in China, and this incident rose awareness of this option. Suddenly, thousands of women expressed admiration toward Xu’s strong will and as the story went viral, more and more women came forward in favor of the procedure. Mary is one of them: “If I can store my eggs, I can become really free by taking control of my body, and I don’t want to worry that someday I won’t be able to give birth to a baby.”

But the hopes of these women were crushed when state media outlet China Central Television (CCTV), reminded people on Weibo that unwed women were not allowed to freeze their eggs.

Egg-freezing technology, or human oocyte cryopreservation, has existed in China since the 1990s, and in 2001 then Ministry of Health stipulated in the Assisted Reproductive Technology Regulations that the procedure is only available to those who have a valid reproduction permit, which can only be acquired through marriage.

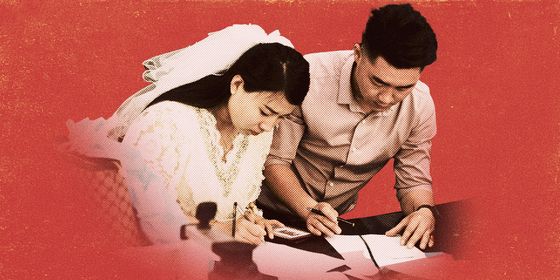

Indeed, a woman must show her ID card, marriage certificate, birth permits, and proof that her partner is suffering from fertility difficulties before using the technology, which is classified as a supplementary IVF (in vitro fertilization) measure.

Lu Guangxiu, president of the Reproduction and Genetic Hospital of CITIC-Xiangya in Changsha, Hunan Province, one of the few hospitals eligible to perform egg-freezing procedures, says that they allow single ladies to freeze their eggs, but if they’re going to thaw and make them embryos, they need to provide a marriage certificate and a birth permit.

Following the CCTV post, the debate picked up steam, with many people complaining the government was violating single women’s right to bear children.

Li Yinhe, a well-known Chinese sexologist, argued that the government’s regulation is outdated. “The Constitution states clearly that citizens are entitled to reproductive rights, and no legislation has ever said that single women can’t have babies.”

“Single women’s reproductive rights have not exactly been in the public eye; in the recent past most women would get married in their early 20s to avoid their parents’ ire. But today, the number of unwed women has grown dramatically and more women are realizing they have a right to children without marriage,” Li says.

Considering the policy limitations, many medical experts also suggest young women should not try this procedure, citing health risks and ethical reasons.

The procedure for retrieving eggs may cause complications such as hemorrhaging, inflammation, ovarian function damage, and the recovery rate of frozen eggs after thawing is 70 to 80 percent, says Sun Xiaoxi, a doctor at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University, adding that freezing the eggs may also have uncertain effects on offspring.

Lu cares more about the potential children’s lives more than the potential mother, but expresses this in potentially problematic terms by saying, “A complete family is the foundation of personal happiness.”

But as people are struggling to climb over these policy walls, those inside point out how hard it is to be a single mother in China overall, which is perhaps an even more harrowing hurdle than the policy barrier. The national policy that forbids single women from having children through supplementary methods is just the start of the problem.

Tan Xiumi, 30, an unwed mother who lives in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, with her five-year-old child, can only summon a bitter smile when talking about the issue of “single women’s reproductive rights”. “Single ladies without kids today will agree with having baby outside of marriage, but they won’t think that way after really having kids,” Tan says.

“Even if someday, the ban on the use of IVF is lifted, trust me, it’s unlikely that single mothers and their children will enjoy the same kind of life,” she says. “There are institutional barriers and discrimination against single mothers.”

Five years ago, when her boyfriend broke up with her and she found herself pregnant, she made the decision to give birth, and the first problem she faced was a financial one. To get a hukou, or household registration, for their children, unwed mothers have to pay a fine—known as a “social maintenance fee”—designed for couples who violate family planning policies.

Under China’s household registration system, a hukou is the very foundation of a person’s right to live, receive education, work, and claim social welfare. Without hukou, the children are classified as “illegal”, lacking any existence in a legal sense, let alone the rights accorded to a citizen.

“Unwed and Undefended” is a story from our newest issue, “Mental Health”, coming out soon. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.