The sophisticated ways in which China and the US are transforming games for each other

Somewhere along the way to China, the skeletons in World of Warcraft mysteriously vanished.

Most were quick to assume that the change to the world’s largest Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game (MMORPG) was the result of edicts from China’s censorship bureaus; after all, they had been known to make bizarre demands from time to time, such as banning time travel from TV or banishing the cleavage of Tang Dynasty royalty.

This, however, was only a half-truth. While regulations do discourage the promotion of superstition, the game developers, facing an expensive, potentially lengthy and risky approvals process to get into the Chinese market, most likely decided to take the safe route and axed their own skeletons before players or censors even had the chance.

It was one startling example of the vagaries of computer game localization—a process in which game developers tweak their product to suit a foreign market, which has become a multi-billion dollar international business and when done well involves careful analysis of everything from design preferences, storyline tweaks, political and cultural expectations, and above all else figuring out what people from different cultures will and won’t pay for.

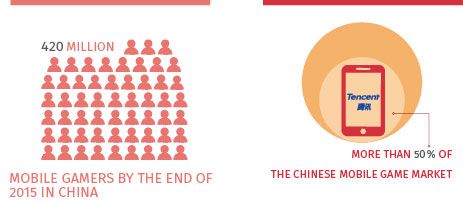

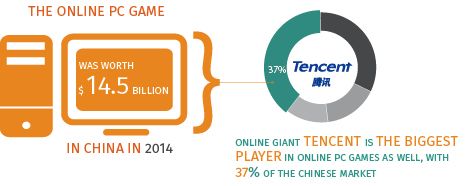

With China and the US now representing the world’s largest game markets and producers, developers on both sides of the Pacific are trying to find ways to tap into each other’s markets.

It’s an extraordinarily difficult endeavor in a new and rapidly evolving industry. MMORPGs, mobile platform games, and first-person shooters are all incredibly different beasts with different markets and needs, and the industry itself has transformed from mere translation to something else entirely.

CASH CLASH

An apocryphal tale circulates among the game development community in Beijing. The CEO of a well performing game company scolded his developers by saying: “We are not here to make great games.”

True or not, it’s a powerful illustration of the tension between sometimes idealistic developers and their profit-oriented masters. This tension is hardly unique to China, but there are certainly aspects that make the “profit” part of the equation more intense. The dizzying speed at which games are churned out by Chinese companies, often without much originality or customer support, has meant China and other East Asian companies have had to be at the cutting edge of monetization efforts for decades.

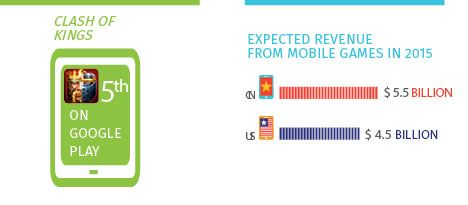

Certainly, stepping inside Elex, a stone’s throw from Beijing’s tech district, it is easy to see that Chinese companies have stepped powerfully onto the global stage. Elex created Clash of Kings, one of the top games internationally on Android’s app store. It’s a powerful achievement for a Chinese company and vindicates their approach: create an international success first, then focus on the

Chinese market.

In the company’s office space, foreign developers fill out forms to apply for jobs alongside the predominantly Chinese staff. Initially funded in 2008 to the tune of 3 million USD by China’s software giant Tencent, a post by the company describes it as the largest “social game” company in Asia and the fifth largest social game company worldwide, with 40 million active users.

From the outset it was internationally focused. Initial challenges included international payment systems (no mean feat given controls on international monetary transfers) and partnering with other companies. CEO Tang Binsen found himself on Global Entrepreneur’s list of Business Elites under 40 as the company rapidly expanded.

In one way the company has retained the strengths of the Chinese approach; its aggressive but nuanced approach to monetization has paid off, with over 10 million USD in turnover each month, and the company has approached it in a manner far that has proven to be far more sophisticated than its contemporaries.

But those contemporaries don’t necessarily have to be adept at localization themselves. The industry has spawned its own specialist companies which can be choosy about which titles they select for localization.

Matt Leopold is Business Development Manager with Yodo1, a company focused on bringing Western mobile games to China. He points out that monetization is a delicate endeavor. “It depends on the game, but often it’s whether it is monetized earlier rather than later. At certain points it’s whether you are required to buy an item or wait a long time. These are decisions we have to make to ensure it caters to the Chinese players.”

When it comes to payment, there are some key differences between Chinese players and Western ones. “In some cases we have had to convert games from a payment framework where you pay to download, to a free-to-play framework with in-app purchases,” Leopold points out. “This has been more of a common model in China, but you are starting to see more acceptance of paid games.”

If a developer pushes too hard on monetizing a game it can turn gamers off entirely, whether they are from China or the West. As a general rule of thumb, Chinese gamers appear far more willing than their Western counterparts to tolerate fairly restrictive in-app purchases, paywalls, and payment for necessary booster items, however they are much less willing to pay upfront for a game.

Joshua Dyer, a former game localization specialist who worked with Beijing-based companies to localize their MMORPGs to Western markets, points out that this has created online worlds which might come across as off-putting to some Western gamers. “One characteristic of a lot of Chinese MMORPGs is that basically they are a class society. The free players get to play and have fun, but they’re basically cannon fodder for the rich players. The rich players spend money and become powerful and get to live out these fantasies of ruling a kingdom. That model doesn’t translate well to Western gamers.”

“Game Theory” is a feature story from our newest issue, “Mental Health”, coming out soon. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.