Even after its destruction the Kowloon Walled City has maintained a hold on imaginations worldwide

To the unlicensed dentists and doctors who plied their trade in their ramshackle clinics, prostitutes, triad gangsters, and fugitive Kuomintang soldiers, the Kowloon Walled City (九龙城寨) was an unregulated, tax-free oasis that shielded them from interference from the Hong Kong authorities.

But, right up until its evacuation and subsequent destruction in 1993 and 1994, the majority of the inhabitants simply called it home.

Although it would become associated with crime and lawlessness—with Hong Kong residents from other areas often shunning it—the estimated 33,000 residents who were living on the 2.7 hectare patch in 1987 lived reasonably normal lives. By that point the crime and population density had significantly decreased, but it was still the densest population of human beings the world had ever seen. Most likely, nobody will ever know exactly how many people lived there at its peak.

Before it became a cradle for organized crime and inspired imaginations worldwide, the Kowloon Walled City began its life as a trading outpost way back in the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279). For centuries, the outpost saw little action, save for sales of salt. Later it was intended to be a bulwark against British colonial expansion from Hong Kong, but in 1898 all this changed, when an agreement between the colonial British authorities of Hong Kong and the Qing government left it in territorial limbo, and British authorities invaded, expelling many Chinese.

The physical walls came down, pillaged for building materials. But the diplomatic walls remained, and in this vacuum a wooden shantytown began to form. Despite deadly fires and occasional efforts from the British to evict them, the squatters persisted.

When the colonial authorities in 1945 began enforcing bans on vice, the Kowloon Walled City became a haven for those seeking to evade the crackdown, augmenting the existing population, many of whom had fled China’s civil war. The result was a community which steadfastly opposed any form of authority.

A 1976 aerial photo of the Kowloon Walled City, courtesy of the Hong Kong Government Information Services

In the 1950s, the triads slowly but surely began to exercise control over many aspects of the Walled City, but even then it remained a fragmented society, built upon the pragmatic needs of the moment. Between the locals who ventured into Hong Kong to tap water and electricity mains to serve their needs, and the vibrant black markets in vice, the city began to develop a reputation, fueled by the competing narratives spread by the British and Chinese authorities.

It remained at the center of a diplomatic and legal tug-o-war between China and the British, with criminals caught in the city being extradited to China, until 1959 when the British asserted more legal control.

Drugs, prostitution and all manner of crime proliferated throughout the dank, crowded halls, but if you were a long-term resident and knew which areas to avoid, your life continued as normal.

As its population swelled and an economic boom greeted Hong Kong in the 1970s, the buildings grew taller, restricted only by the flight path at the nearby airport—one of the few regulations followed within the community. The 70s and 80s were also the time when a series of police crackdowns led to a massive reduction in crime—the crackdown built up slowly, as the police force also had to root out corruption in its ranks before it could quash rather than compete with the crime in the Walled City and launch effective raids.

But it is the dystopian image of the Kowloon Walled City that endures the most in pop culture—the densely populated, crime-ridden block of high-rises, jammed so tightly together the buildings themselves resemble castle walls. This inspired everything from Gotham City’s criminal neighborhood of “The Narrows” in the 2005 film Batman Begins, right through to computer games and even a Japanese theme park.

But as Seth Harter, who was in 2000 an academic at the University of Michigan, outlined that year in a paper entitled “Hong Kong’s Dirty Little Secret”, viewing the Walled City as a bastion of crime is too simplistic. “At the time, pro-British factions portrayed the Walled City as a Chinese enclave, independent from the remainder of the colony, to cast it in the role of the dark antithesis of the colonial order,” he wrote.

He said that the clients that utilized criminal enterprises in the city—be they the striptease joints, opium dens, gambling halls or even dog-meat stalls—were often drawn from outside the Walled City itself.

And in the 60s and 70s, as crime boomed, civic awareness rose as well—in the form of the Kaifong Committee (街坊会), which began as a group of concerned residents who banded together to protect and maintain the Walled City. In stark contrast to the triad rule over the area’s dark underworld, the Kaifong Committee quite literally brought light to the community; they worked to provide cleaner areas in the city, as well as lighting and signs. In 1984 they even organized a funding drive to aid famine victims in Ethiopia. The Kaifong Committee—made up largely of well-meaning, middle-aged and elderly residents—could not have been more different from the gangsters whom Hong Kong residents feared.

And in the 60s and 70s, as crime boomed, civic awareness rose as well—in the form of the Kaifong Committee (街坊会), which began as a group of concerned residents who banded together to protect and maintain the Walled City. In stark contrast to the triad rule over the area’s dark underworld, the Kaifong Committee quite literally brought light to the community; they worked to provide cleaner areas in the city, as well as lighting and signs. In 1984 they even organized a funding drive to aid famine victims in Ethiopia. The Kaifong Committee—made up largely of well-meaning, middle-aged and elderly residents—could not have been more different from the gangsters whom Hong Kong residents feared.

So as the Kaifong rose and crime fell and Hong Kong’s property prices soared, the area became less identified with crime, and more of a place for the poor to seek refuge. By the 80s it was just starting to shed its disreputable image and become little more than a particularly dense, albeit poor neighborhood.

Suenn Ho, today an urban designer based in the US, conducted in-depth research into the Walled City as part of a Fulbright scholarship. She and others who researched the city, such as Aaron Tan, a Harvard University architecture student who was writing a thesis, were struck by how the community evolved “organically” under its unusual circumstances.

Ho points out how common areas were built as a bare necessity for circulation purposes, but that didn’t stop socializing from occurring—the outdoor balcony areas were so tightly packed together that residents chatted to one another between these “linked” areas, as they also did on the linked rooftops.

These extensions were so widespread that they became an integral part of the structure. Tan observed the two-year demolition process and notes that “it evolved in such a way that these extensions became beams that supported the structure itself”.

Residents also evolved to fit the structure. Tan observed that limitations on things like water and electricity necessitated cooperation between residents. “Insufficient water was provided, so they dug wells. But there was also a lack of electricity, so they had access to power at different times in different parts of the city. They had to ensure they coordinated this with the pumping of the water.”

Thus, cooperation became a necessity for survival. Ho points out that the city had doctors and dentists—unlicensed in Hong Kong but licensed from the mainland—as well as schools, temples, and day care centers for senior citizens. She rejected claims the city was a slum and said many people stayed there for very practical reasons.

Dr. Kwok, an STD specialist, held credentials from the Mainland, but that were not recognized in Hong Kong – as such, he aided residents in the Kowloon Walled City.

But it was certainly no utopia. The residents lived under difficult, humid circumstances. Ho recalls one occasion she met and interviewed a man in a surprisingly spacious apartment. “There was a giant clear sheet covering most of the ceiling. The plastic sheet contained a giant pool of yellow liquid, and he seemed surprised that it bothered me when he told me the sheet was collecting liquid seeping from the apartment above.”

There was also division. Jackie Pullinger, a missionary who spent decades working with the poor in the Walled City, wrote in her memoir that the triads effectively divided the city in two. Harter also points out that even the Kaifong did not succeed in forging a collective identity and promoting the Walled City’s history beyond its own walls until the specter of destruction loomed over the city. This is likely to have been when the sense of nostalgia for Walled City history picked up steam beyond the Walled City itself—and it is notable that this nostalgia still exists today, as exemplified by the city’s hold on pop culture.

Although the city’s demolition was not completed until 1994—after a laborious two-year process that involved “peeling away sections”, as Tan put it—its death knell was sounded a decade earlier, in 1984, when the joint declaration was handed down. That was when it became clear when and how Hong Kong would be returned to the Chinese authorities. With the stroke of a pen, the Walled City was no longer a pawn at the center of diplomatic brinkmanship, but would soon become an undisputed part of China’s territory. Secret discussions began between the PRC and the colonial authorities, and on January 14, 1987 the British announced they would tear down the Walled City and replace it with a park. Right on cue, the Chinese authorities expressed their enthusiastic support. That very same day, the Hong Kong government dispatched plainclothes police and over a thousand members of the surveying and mapping department to determine the details of the city as well as occupancy: 33,000.

The haste with which the operation was carried out was believed to be due to fears that the announcement (and the expectation of compensation) would send Walled City land prices skyrocketing. The Kaifong, along with residents, went into overdrive promoting the history of the Walled City, as residents feared they would be left with nothing.

In the end, the residents were relocated to other parts of Hong Kong, but the city left its legacy in a number of ways, from pop culture to architecture. Tan notes that the “resilient DNA of Hong Kong” continues to express itself in today’s densely packed neighborhoods and their exterior cages reminiscent of the Walled City. “In that essence, it still lives on.”

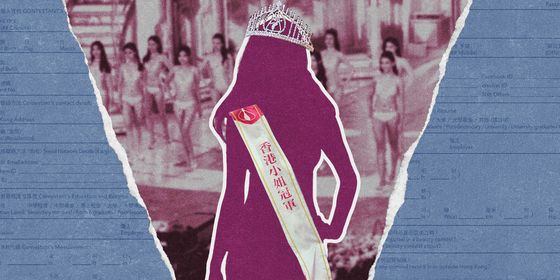

Photos courtesy of Suenn Ho and the Hong Kong Government Information Services