Photographer Ma Hongjie documents China’s rural underbelly

Now a photojournalist for Chinese National Geography magazine, Ma Hongjie has become known for projects that probe deeply into the lives of interesting communities: wife buyers, street performers working with monkeys, Yellow River dwellers, and most recently, regular families across the country and their possessions.

Ma worked on most of these long-term projects when he was a local reporter in Zhengzhou, Henan province in the 1990s, later publishing book on buying a spouse, Getting a Wife in the West (《西部招妻》), a tale of how a polio victim bought four wives in eight years; each divorced him in the end, including one mentally-challenged woman and one that swindled him out of 20,000 RMB.

Ma insists there is no judgment in his work: “Don’t judge simply by good and evil.” This mantra has kept him successful and has made him a trailblazer in his field.

What was it like being a reporter in the 90s?

One still had a passion for being a reporter—eager to promote justice. But by the time I went to Henan Legal News, I couldn’t take it anymore. The difference you could make as a reporter was inconsequential to the system. A reporter’s efforts were like the Chinese saying, “Ants failing to push against a big tree.” The people were wronged, and cases of injustice—you knew they were real, and everyone knew they were real— couldn’t be solved. If you advocated for the wronged, you’d face corrupt officials, censure, or retaliation. Being a reporter was extremely difficult. Not much has changed. If the political system doesn’t change, the news system won’t really change either. That pained me, and I sought to escape from it. So, I went to Chinese National Geography in 2004.

Yet your projects often feature people living in difficult conditions.

Well, that’s different. By putting them under the spotlight, I call for other people’s help, rather than single-handedly effecting help myself. For example, because of the popularity of the “Street Performers with Monkeys” series, many people offered to help the performers, even donating money. I also help them in my own way. Just recently, some performers got arrested and illegally detained. They could do nothing except ask me for help. I asked a friend to investigate the story undercover for two weeks. The performers were released with no legal punishments after the story went live. They finally got their compensation, but one monkey lost its life.

Train-hopping with monkeys and performers in 2004 at the Beijing South Railway station

How did you first get interested in the street performers with monkeys?

When I was little, I grew up in two environments: the rural with my grandmother during holidays, and the city during school semesters. I was fascinated by rural people’s original—or perhaps backwards—lifestyle. There is no evil in them, yet perhaps there is a virtueless side. So, I began photographing the countryside, which led to my themed projects.

Shooting the performers is complicated. First, you need to get to know them, their nature, and find your own place as an observer. I wouldn’t just stand by if they went too far, but I haven’t seen them commit any terrible crimes. I distinctly tell them that my lens and my portrayal will be objective. I won’t meddle, unless things really get out of hand. Even in Guangzhou, when they were handcuffed, I stayed out of it to see how they’d respond. They do have their own rules, a kind of “honor among thieves.” For performers who train monkeys, the ground rule is: no kneeling and begging; dignity comes before money and food. Another rule: freeloading, yes; stealing, no. Once on a train-hopping journey to perform in another province, they found cookies in the compartments. They ate those, but wouldn’t steal more to sell for money.

Yang’s son became close to the baby monkey, even going so far as to sleeping with it side-by-side. For performers, monkeys are part of the family.

You’ve been shooting street formers for 12 years. What changes have you observed?

The passing of time. When I first started shooting, Mr. Yang was a young lad, and now he, as I often joke, “looks more and more like the monkeys”. Even his gestures, like the way he squats, have become quite monkey-like. There are changes in his family, too. His son, who used to train monkeys with him, doesn’t do it anymore because he thinks it’s a dying profession. The descendants of these performers no longer perform. Some, like his son’s wife, condemn his profession as inferior. Individual performers are perishing. Society is unlikely to permit their exploitation of monkeys much longer. In the old days, the poor tried to look for a way to make money, and they teamed up with monkeys—of course that was hundreds, even thousands of years ago. Now, we have become more civilized; our level of awareness, of conscience, of ethics, all deter the continuation of the trade. For the performers, though, it is simply a traditional trade they’ve inherited.

What can they do about this?

I advised them to raise their monkeys as pets, a concept urban dwellers would be more likely to embrace. I also suggested that they incorporate traditional culture into their performance, rather than the shouting and fighting acts they have now. Yet, to most of them, the quickest way to get money is the best. In the old days, monkey performances were just a cover for selling needles in the late Qing and early Republic periods. Needle sales gave them a profit margin; the performance itself was free. Back then, monkey performances were more sophisticated. The monkeys wore hats, masks, and clothes like regular theater performers. The monkey owner would sing, a cue for his monkey to open the suitcase, put on a hat, and start the show. For individual performers nowadays, improvements would be too much of a hassle. As long as they can get money, the means and form do not matter.

A monkey and a performer slurp noodles together. Before the performers eat, the monkeys are given the first bowl as a sign of respect.

Can you tell us more about your project documenting wife-buying?

After the book came out, three people called me up, asking me to help them buy wives. I was surprised. I never thought, even considering the gender imbalance in China, that they couldn’t find an appropriate partner with a decent background. Now, there are a lot of old bachelors in the rural areas. The girls from my village, for instance, have all left. They are more willing to marry outsiders, people they can connect with, who are more cultured and with more money. When I first started this project, the only wife-buyers I saw were the handicapped, really old men, and divorced men. Their needs were simple: to start a family and have descendants.

Lao San’s wedding ceremony with his first wife, a mentally-challenged girl, in the winter of 1998

Does this business mainly take place in impoverished areas of Henan province, as many assume?

Not just Henan, but also Hebei, Inner Mongolia, and Ningxia. Educated people wouldn’t do things like buying wives; they would go through dating agencies, dating sites, and such. There is a class difference. The wife-buyers belong to the lowest classes.

An old matchmaker in her 70s with her “adopted” children, bought for 200 to 300 RMB each. She will sell them into marriage in later life.

What is your opinion of the old matchmaker who buys girls and sells them as brides?

That is the local way of living. You cannot judge. In those places—it may have improved somewhat now, but not by much—when I went, they were so poor that they couldn’t afford to mend or wash their quilts. By selling a little girl, at least she would be fed. Once you understand that context, you cannot criticize it from a moral high ground. Rather than letting a baby girl starve, the matchmaker will marry her off to a good family and receive some money a decade later. What’s wrong with that?

You’ve shot rural China for decades. How has it changed?

Nowadays, people eat better, and their basic needs are met. In terms of ethics and education, however, there is no change. People don’t know what they want for life or themselves. A nation’s transformation needs to begin with ethics and education. Just changing on the most basic level of sustenance still leaves people ignorant.

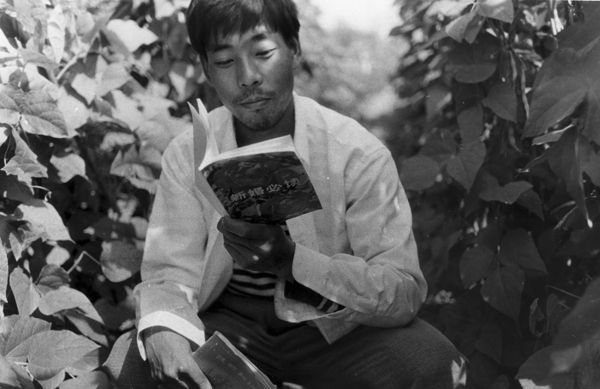

Lao San reads up on sex education. Due to his wife’s mental disability, she doesn’t understand or accept sex. After his failed attempts, he asked for a divorce.

Do you think the countryside is more interesting than the city?

No, cities are just as interesting. For example, there was a news report of a family who lived in the sewers in Beijing. The reporter didn’t do it right. He only reported the story and didn’t call on the people who could help. Instead, he ruined their lives. These people had a place to keep warm in the winter. It was the media coverage that robbed them of their shelter.