The rejuvenating, spiritual power of tea done right

Madame Peng’s day starts at 4:30am, when the night’s darkness begins to thin. She goes out with a torch to look for her 14 ducks that didn’t come home the night before. The other residents in Peng’s backyard—pigs and chickens—were already stirring restlessly and making noise. In half an hour, the whole village would wake and come alive. Elderly women can be seen dancing on the open ground opposite Madame Peng’s hostel, and the locals begin preparing themselves for work.

In early May, Langu Village plays its part in the hectic processing of tea. The shops along the main street seem abandoned, and women, both young and old, sit outside their houses patiently hand-picking yellow leaves out of high piles of freshly baked black tea. Behind them is a long row of yellow two-storey houses that make up the main street, some have stood for over 100 years and have elaborate, auspicious engravings on their gates. The houses are built from large mud blocks made from a mixture of mud, bamboo, and sugar. As delicate a mixture as this may sound, it is surprisingly resilient. A river runs along the street, and downstream stands an ancient pagoda, which was built to tame a river demon that was believed to cause ferocious local floods. For now, the river is more than calm, and you can see the pebbles and fish through the shallow, crystal clear stream alongside gigantic blooming berry trees that cast their shadows on the water.

Madame Peng’s hostel stands at the other end of the river. She is a stout woman; although already in her 60s, she still looks healthy and energetic. She lives comfortably off a school teacher pension, as all three of her children are now securely settled down in big cities. But, nevertheless, she works hard to maintain her hostel, which she named “Starlight”.

Although Langu Village has its attractions—its graceful ancient residences; a waterfall the locals call “Rice Falling into A Pot” (白米落锅); green, undisturbed mountains perfect for hiking; and a delicious specialty known as “Langu smoked goose” (岚谷熏鹅)—we were the only tourists there. Lodging in her hostel turned out to be a brilliant choice as she is an amazing cook. Her kitchen smelled of a heady blend of firewood smoke and frying food. Only later did we learn that Madame Peng was a prize-winning chef in the village and had even taken the main prize at the White Geese Festival a year.

Freshly-picked tea leaves await the arduous process of tea making

“The festival is held by the village to encourage us to raise fowl. Now, fewer and fewer people are raising fowl like I do, and a lot of farms are wasted,” Madame Peng opined. Besides raising animals, she also works on a small vegetable field to keep herself fully occupied. “Nowadays, no one wants to do such a hard, dirty job that barely pays. Working on construction sites is easier and much better paid. People don’t understand why I work so hard. I only tell them that I have been working hard all my life. I simply love labor, and idleness makes me feel unbearably empty.”

Fresh lumber often accompanies local houses so that they can readily bake their tea leaves

Fortunately, Madame Peng’s son-in-law, Chai Wei (柴玮), understands her well. Chai is 50 years old and almost bald, but he is lean and jovial, looking much younger than his years. He believes that hard work alone is the source of wisdom and loves it almost religiously, much like his mother-in-law. As he would walk through the village, he often rubbed his hand against the rough mud walls with a loving pride. “This is what I call a life.”

However, Chai’s words, which hint at him being the small town or village type, don’t quite ring true, and he is not a Langu Village local. Since his youth, he has been a member of China’s elite, one of the first to go to university after the Cultural Revolution, obtaining a Master’s degree in literary theory at Beijing Normal University. In 1989, he went to the U.K. and obtained an LLB law degree at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He worked as a lawyer in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Xiamen and then went into foreign trade in Europe

and China. In 2006, at the age of 44, he looked every bit the successful, sophisticated, middle class man. Except, that man was unhappy.

“Alienated.” He uses the Marxist word, speaking of his metropolitan days. “In the city, man is alienated from nature and from himself. My work was extremely professionalized. In a highly developed society, everyone is pigeonholed, and you are just another screw in the gigantic machine. But, what’s so good about living in our times is that you have the freedom to choose what you want.” And he did choose. He turned himself into a “tea man”.

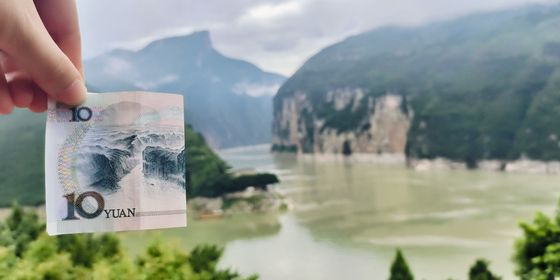

The fittingly named Chai started by buying a small hill that nobody wanted, with some tea farms that had not been looked after for many years—a land of treasure for tea makers because older trees produce better quality tea. However, eight years ago, making tea here was not as profitable a business as it is now. Even the much famed Red Robe (大红袍)—one of the most expensive tea species in recent years— would only sell for a mere 30 RMB per kilogram. In Langu Village, villagers chiefly lived by farming and simply made tea for their own consumption rather than for general sale. As a result, a lot of old tea trees were left to survive in the wild on their own.

Chai speaks about tea with the zeal a monk might speak about Buddhism and claims that his enlightenment to the spirit of tea came from the local tea masters, chashifu (茶师傅). “In Wuyishan Mountain, a lot of tea masters were poor people who came from neighboring Jiangxi Province. They are usually undereducated—they probably haven’t even finished their primary schooling. Without any means to make a living in their hometown, they had no choice but to come here to be apprentices in tea workshops. Making oolong tea takes about 25 hours of constant work. However, after many years of such hard labor, some of them became enlightened as to the spirit of tea. They eventually became masters themselves, and seemed to have cultivated a touch of zen in their character and very distinguished tastes.”

Chai’s tea farms are five kilometers from the village and he took us to pick tea with him on a fine early morning. The landscape along the way was breathtaking—the mountains covered by lush, exuberant greenery, especially bamboo, which, from a distance, give the mountains a furry, tender green look. Living in such a verdant paradise, it is no wonder Chai now considers Beijing uninhabitable. We didn’t realize we had hit his patch until he pointed out, “These are my trees.” We expected cleanly cut bushes uniformly covering the whole mountain, layer after layer, curving into the distance. But his trees were mingled among tall weeds just like wild bushes. We stood in the waist high grass and felt lost.

Carefully, Chai engages in the precious last stage of the tea making process: enjoying his hard labor

“I know my farms are no good for a camera,” Chai said. “But the tea trees need to grow in a natural environment and compete to survive. Nature will take care of them. If you get rid of their competitors and enemies, the production will rise, but it’s at the cost of the tea’s flavor,” he explained. Believing the tea leaves have a special capability to absorb the smells of their surroundings, Chai has his own particular farm management techniques. He refuses to apply synthetic fertilizer or expand his farm by cutting down any of the nearby wood. He is not even bothered to see his tea leaves slowly gobbled up by hungry worms. As a result, his production is only a few hundred kilograms of tea a year, a small fraction of what is usually

produced on an industrialized tea farm. The tea farm that he takes the most pride in is hidden on a secluded hilltop that takes even an experienced, mountain-hardened villager three and a half hours to reach; the growth along the way is so thick that every year they have to machete their way to it. “And that tea tastes of mountain breeze,” says Chai.

Chai’s tea partner is his cousin, Wu Chengda. When they first started out, it took two years before they really understood the art of tea making. “At first we strictly followed our master’s directions, but the tea produced a strange flavor,” Chai says. “We gradually realized that there is no standardized procedure to tea making. To bring out the best in your tea, you need to take everything into account—the tea leaves’ condition, the weather, the air— and have a good understanding of how nature works. After all, good tea is not made by a human, but through the doings of nature (好茶不是人造,是天造).”

In the afternoon, we rest with Wu Chengda, a 40-year-old man with friendly eyes, in his farmhouse. Wu and his wife were all in the middle of making tea. Even his two daughters, aged 12 and 10-years-old, were on hand to help out. Despite the heavy work, the whole family was in a merry mood. When oxidized, a little magic happens in the tea leaves, and they start to give off a fragrance that resembles the smell of flowers or fruit, smells that fresh tea leaves do not possess. The whole yard becomes filled with this fragrance. “The entire process involves more than a dozen steps, and the changes that take place in every step will give the tea a new fragrance. It’s different from, say, Lipton tea where the flavor is artificially added. This is

the magic of nature,” Chai explains.

China’s tendency for ostentation is threatening to hurt the tea makers in Wuyishan Mountain. “Now, people are all talking about land marketing, rural capital flows, expansive farming, and things like that,” Chai says. For him, once the tea business in Wuyishan starts yielding to the market in such a way, it will lose its soul. “We are lucky that at present most of the land is held by individual farmers instead of being concentrated in the hands of large industrialized tea factories. That’s why every household makes tea differently, and every tea

master can have his own personalized style,” Chai says. “For example, the Narcissus (a species of oolong tea) made by a family living on this hill can be different from the family living opposite them, just a valley apart. That’s what makes Wuyishan tea so intriguingly good.”

Chai’s Huiwen Tea House in Fuzhou

Chai runs three teahouses in Fuzhou and Shenzhen, called Huiwen Teahouse (汇文茶社). However, for all his love of hard work and his passion for tea making, Chai is hardly a diligent businessman, and there are no traces of the lawyer he once was. He updates the WeChat account for his teahouse about once a month. He occasionally mentions that he wants to build a

website for his farms so that people can trace down the tea they are buying to specific trees, but there is little sign that he will actually put that into action. “I know I need to sort a lot of things out and market my tea,” he grinned. “But life is too comfortable to hurry. Living in this very small remote village, everything can wait for another day. I’m so comfortable with my life that I always procrastinate.”

As our travel continued southward we dropped by his teahouse in Fuzhou. Chai greeted us cordially. His teahouse is an exhibition of his tastes, quaint in a good way: porcelain tea-ware that he ordered exclusively to resemble a Tang Dynasty (618-907) set and tea vessels that are shaped in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) style are all on show. He also has a habit of collecting all things handmade. Once in a while, a friend of his drops in and joins us at the tea table. “This is another thing that I love about tea,” he says. “Tea lovers are interesting people, and tea friends are so much better than wine friends.” We brought some of his tea back to Beijing and bitterly missed the food cooked by Madame Peng. Unfortunately,

Beijing’s water quality ruined some of the tea’s good taste; Chai lamented grievously when he heard this. Yet the fragrance remained, pleasant and strong, a reminder of the magic touch of nature and the people who do their best to preserve it.

You can contact Chai Wei at “china_tea_time” on WeChat. He speaks English and is always ready to talk about the Tao of tea. (Huiwen Tea House, 0591-87623916, 13600183966)