The tale of a long dead religion that changed China’s political landscape

In 228, in what is now Iraq, a boy of 12 had a vision. He saw the world divided into a great battle of good and evil, the sons of light caught within the flesh o f a wicked earth. The vision came to him again when he was 24 and he began preaching the word of his new faith. The boy was called Mani, a subject of the Persian Empire, which would eventually execute him as a heretic in 276. By then, the religion he founded, Manichaeism (摩尼教), already had millions of followers across the Empire and beyond. A few centuries later, it would reach into China, becoming, briefly, a competitor to Daoism and Buddhism for the souls of the Chinese people. It would survive centuries of persecution, only to eventually be driven extinct, remembered only by scholars.

Mani’s beliefs were a hectic mix of Buddhism, Zoroastrianism (the ancient dualistic religion of Persia), and Christianity, influenced by Gnostic Christian texts and apocryphal Jewish writings. As with Islam, born under much the same circumstances, Manicheans venerated earlier prophets, especially Jesus.

Its cosmology was fantastical, complex, and occasionally baffling. At the beginning o f time, said Mani, there was the World of Light and the World of Darkness—one pure good, the other pure wickedness. They competed in a series of weird and wonderful battles, where armed angels campaigned against a myriad of freakish demons. The human body, in the form of Adam and Eve, was created by Darkness, but the soul came from the World of Light and could be freed into its divine origin. The stark division between light and darkness gives us the term Manichean in English today, meaning to see the world in black and white.

But Manicheans rarely focused on evil, though their legends sometimes seem closer to Jack Kirby comic books than anything else, with their stories of heroic battles, incestuous copulation, and bizarre bad guys. In practice, the faith was a pacifist and ascetic one, sometimes to the point of extremes, with priests abstaining from sex, meat, and even ostentatious clothing. Among ordinary believers, it was a religion of community, cleansing, and devotion.

From its origins in the Middle East, Manichaeism reached out to the rest of the world. In North Africa, the future Saint Augustine was a Manichean before he converted to Christianity. It was a time of missionary fervor across Eurasia. Jewish, Buddhist, Islamic, Manichean, and Christian missionaries fanned out across Asia, yet Judaism’s period of proselytising was much briefer than the others. They reached the furthest corners of the earth; Christian monks were praying in the high places of Tibet as early as the sixth century, where in future years local believers would carve crosses into rocks and write divinations to “the god called Jesus Messiah”. In Europe, Manichaeism was soon stamped out by a dominant Christianity, although Manichean ideas surfaced in Gnostic heresies right up to the 13th century.

In Asia, however, the followers of Mani competed in a much more diverse and competitive spiritual marketplace. Manichaeism’s great coup in Asia was the conversion of the Uyghur Khanate, a massive Turkic Central Asian power that spanned from the Caspian Sea to Mongolia. Tengri Bogu, the Uyghur Khan, was converted by Iranian Manichean preachers and declared it the official religion of his empire in 762. The official memorial of his conversion praises the religion for turning the Uyghur from “blood sacrifices to a region of vegetarians, from a state which indulged in excessive killing to a nation that exhorts righteousness.”

His enthusiasm for Manichaeism may have been a way of countering the influence of Tang Dynasty (618-907) China, the Khanate’s most feared rival; China’s neighbours to the north and west looked for ways to forestall the Middle Kingdom’s cultural and economic influence. But paradoxically, ended up giving Manichaeism a way into China itself.

Manicheanism initially won a frosty reception in China. The religion had seen a boost in China, following an influx of Persian refugees and traders in the early eighth century, but in 732, its practice was strictly limited to foreigners, and locals were forbidden from converting.“The doctrine of Mani is basically a perverse belief…and will mislead the masses,” wrote the imperial edict banning its practice. It wasn’t just advocates of indigenous Chinese ideologies that feared the coming of the new doctrines, however; Buddhists, who saw the Manicheans as rivals for the souls (and the donations) of Chinese, were often among its fiercest opponents. In return, Manicheans claimed that while Buddhism might be the “Great Vessel”, theirs was the “Superior Vessel”.

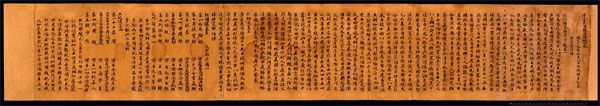

The Chinese Manichaen Compendium. Some of the most complete works of Manichaen beliefs are found in China.

China advocates often boast of the country’s supposed history of religious tolerance. But in truth, the treatment of religion only looks good compared to the barbarities of medieval Europe. The marketplace of divinity was fiercely competitive, and the losers in the competition for the court’s affections suffered grim fates. Heretical texts were rooted out with inquisitorial intensity, aided by networks of religious informers, though exactly what distinguished the heretical from the heterodox varied wildly year to year. Yet the Tang were keen to stay on the good side of the Khanate. The Turkic peoples, initially the great rivals of China in the early years of the Tang—although the Taizong Emperor (唐太宗), the dynasty’s co-founder, rumoured to be a quarter-Turkic himself—became a mainstay of the regime, hired to fight the countries’ battles elsewhere. As a result, the Tang turned towards a reluctant tolerance of Manichaeism, and soldiers and white-clad, long-haired priests alike preached the word of Mani across China. Manichean temples became common in Chinese cities, often in the Uyghur districts. During its travels across Asia, Manichaeism seems to have picked up many Buddhist ideas, and to have shed some of the harsh dualism and Gnosticism that made the faith famous. But followers distinguished themselves from their religious rivals by their vegetarianism, far more strictly practiced than among Buddhists, their refusal to shave their heads like Buddhists, their veneration of Mani and Jesus, and the careful copying of their scriptures, to the extent that texts “separated by four centuries and the whole of the Eurasian landmass”, are virtually identical.

Influences of the Buddha of Light clearly appear in Manichaen beliefs.

As with many of history’s losers, our record of Manichaeism in China is written mainly by its enemies. But it’s clear that the religion, like Buddhism, appealed to some people in a way that the formalistic rites of Chinese worship didn’t. The emphasis on personal purity, the strong community of believers, and the morally clear, if supernaturally complex, preaching of righteousness won the faith many followers from outside the Uyghur and Persian communities where it started.

The religious competition between Buddhists, Daoists, Manicheans and others was also a contest of magic. Soothsayers, seers, summoners, and sages sought to outdo each other in wondrous feats, from the casting out of demons and the breaking of the evil eye to the conjuration of gods to converse with nobles or congregations. Manicheans became particularly known for astrology and exorcism, including sometimes being asked to employ their magical skills on behalf of the government.

To our eye, the tales of magic and miracles, of false faiths defeated by pure doctrines and evil spirits cast out, of fortunes told and minds read, of great wonders of endurance performed to demonstrate the strength of belief, may all seem like delusion or chicanery. Indeed, many Chinese scholars were equally skeptical, pointing to sleight-of-hand, confederates, shadow-puppets, and mechanical ingenuity as the source of marvels, especially among the sects they disliked. But among both the public and the elite, these claims were not only credible, but a major source of religious legitimacy.

If you would like to read the rest of this article, please purchase the TV Issue in our online store today!