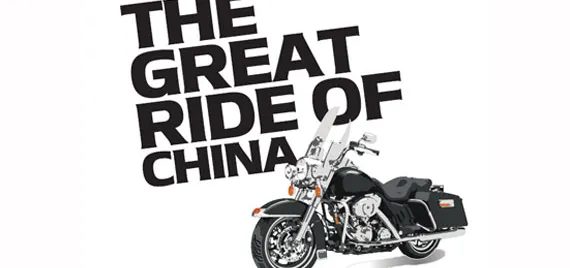

Two rogue motorcyclists attempt to take on all of China

We were in our second snowstorm in as many days. I was gripping the handlebars of our Chinese made CFMOTO motorcycle so tightly that my arms and back were stinging and sore, pain that helped me to forget about the biting cold coming through the facemask of my helmet.

At one rest break, we stopped to have some water and Amy, my girlfriend and faithful travel companion, between dejected shivers, asked, “How much longer are we going to be here?” She knew the answer wasn’t going to be palatable and was reaching out for words of comfort I couldn’t give. “Another 20 days in Tibet,” I answered. “But Qinghai and Sichuan might not be much better.” At the beginning of 2013, Amy and I started developing a plan: a motorcycle trip that would turn into the adventure of a lifetime. What was initially an idea for a one-month motorcycle trip from China’s capital, Beijing, to the southwest province of Yunnan had evolved into what we started calling “The Great Ride of China”—an epic five month motorcycle odyssey through every province in the country, helping to raise money for a domestic charity, Free Lunch for Children (免费午餐). If we were successful, our trip would enter The Guinness Book of World Records for the longest motorcycle journey ever taken within a single country.

When we set out from Beijing on July 19, 2013, it was no different to any other week long holiday motorcycle ride we had taken in the past. This time though, it would cover 33,000 kilometers and take 146 days before we would return.

Before the mountains of Tibet, we had to pass through the deserts of Xinjiang Province. We reached Kashgar, the cultural capital of Chinese Islam; we were at the 11,000 kilometers mark and not even two months into our trip. Here we prepared for the potential three weeks it would take us to get through Tibet in some of the most challenging conditions we would experience on the trip.

Having already seen so much of the diversity that China has to offer—Harbin, Xi’an, Dunhuang, not to mention the Gobi Desert— Kashgar was like being in a different world altogether. Amy and I speak Mandarin, but on spending several days in Kashgar, preparing our trip to the Himalayas, we found that in most places in the city we could only communicate with young children, who studied Mandarin at school.

A bustling street scene in the heart of Xinjiang

Sitting at a food stand, waiting for our lamb kebabs (chuanr) to be prepared by a veiled Muslim woman, we wondered how anyone in Xinjiang got adequate nutrients. It was weeks since we had seen any fresh vegetables. The local diet seemed to exclusively consist of lamb served with some form of local bread (nang) or noodles. Still, every dish was tasty and fresh, despite the lack of greens.

We waited in Kashgar for a week until our Tibetan guide arrived from Lhasa. As foreigners, we were required to be accompanied through the Tibet Autonomous Region, presumably to make sure we stuck to an approved itinerary. Our guide, Ciren, and the driver of their car, Pasang, were natives to the area around Lhasa, but had never been to Kashgar or even Xinjiang Province before. They both expressed a dislike for the local food, exclaiming it as boring (which made me and Amy laugh when we were in Tibet having our third straight meal of yak meat noodle soup).

Heading east from Kashgar we drove along a well-paved, flat stretch of road through barren plains and desert before arriving at a city called Yecheng, which was under strict lockdown when we arrived. There had been some protests just prior to arrival, and police tents were setup on almost every street corner, with large armored trucks making rounds of the streets. When we went to our hotel front desk to ask why our internet was off, we were told the local government had temporarily shut it down until the tension ebbed.

Despite the heightened alert level, people were extremely friendly. One night Amy and I were wandering the streets looking for a place for dinner, and were suddenly engulfed by a wave of young kids. By the look of them, these were Uyghur children.

The small crowd of children walked alongside us and loved that we could speak Mandarin to them, excitedly responding when we asked where we could find a good dinner. Kids being kids, it seemed they just wanted to walk with us as opposed to make a recommendation. We eventually decided by a show of hands and were led to a chuanr place that also served fish and eggplant kebabs.

A typical day on the road for us would be about 300 to 400 kilometers. Since motorcycles aren’t allowed on expressways in China, we usually made do with smaller national or provincial roads. Road conditions ranged from nicely paved and straight, right through to disastrously pot-holed in crowded villages with heavy traffic.

On our first day out of Yecheng, our guide told us that there were no guesthouses or places to camp for over 500 kilometers, a distance covering three mountain passes, and an altitude ranging from 1,000 meters in Yecheng to as high as 5,000 meters on the Kirgizjangal Daban pass.

The only way to deal with a day like this was to wake up early and take only short breaks, stopping no more than 10 minutes at a time for snacks and water. Even if you’re making good time, you do not know what lies ahead, whether it’s road construction, an accident, or a military checkpoint. So we were up at dawn, our bags packed the night before and on the road in good time. Finally, after a week sitting at the footsteps of the Tibetan Plateau we were putting the final Xinjiang city in our rearview mirrors.

It was a slow climb to the top of our first pass; the pavement distinctly wavy as if it had melted and resolidified under the weight of large truck wheels. We were met with threatening half-meter dips and rises

in the asphalt on what seemed like every turn. After an hour of this, the road made one final twist before cutting its way through the last of the mountain.

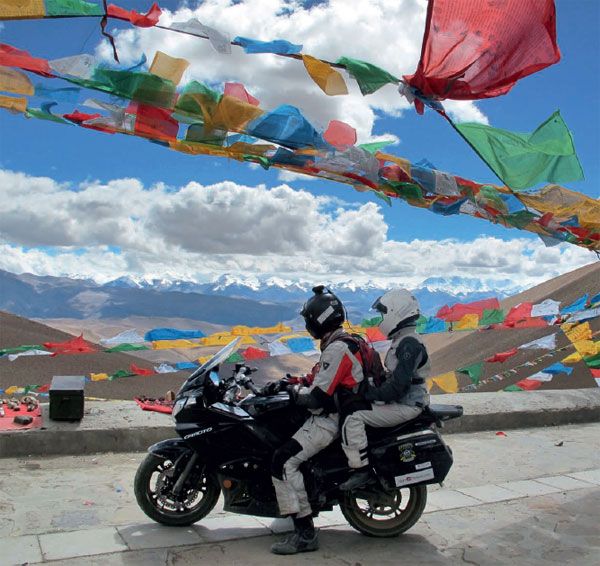

Buck and Amy look back at the Himalayas on leaving base camp

A framed gateway welcomed us to Kunlun: row upon row of perfectly sculpted snow-capped mountains. We took a few seconds to marvel at this sight before tilting our heads back down to focus on the road ahead and the dozens of switchbacks leading down from the pass. It was going to be a long day.

Making our way to the second major pass, Chiragsaldi, we felt the temperature start to plummet. Snow lined the sides of the road, when only a few hours before we had been passing through desert. We needed to layer up with all the clothing we had to keep our shivering at bay.

We made it to the top after an hour, as we desperately tried not to think about the icy-cold seeping into our bones. Looking behind us, the whole valley we had just climbed was covered in a shallow layer of shimmering snow. The dramatic stone mountains above contrasted heavily with the eerie stillness that came from the fresh dusting of snow.

A light flurry fell on us as we took our “lunch” break: some trail mix and, yet more, nang bread from Yecheng. Amy took shelter in the guide truck to try and warm up while I walked around the small parking area to gaze at the barren landscape. After letting a military caravan pass us, we decided to push on and continue down into the snowy mountain range toward Tibet.

That was our last real break of the day. With 300 kilometers left to go before the truck stop where we could stay for the night, we had no desire to get caught driving at night. The ascent to the last pass, however, took us right into the center of a snowstorm. Visibility dropped to about 10 meters as the snow came down around us on the now unpaved switchbacks. We passed another motorcycle coming from the other direction. We both stopped on the side of the road as we saw each other. The other bike also rode two, a Chinese couple coming out from Tibet. Despite being stuck in the middle of a storm, we yelled pleasantries through the wind, sharing in the camaraderie that comes with being foolhardy enough to take a motorcycle through such fierce conditions.

After making it over Kirgizjangal Daban, the storm finally broke allowing us to make our way through the winding valley road into a truck stop. We got gas at the first pumps since Yecheng. As I got off the bike, I knew it was going to be a rough night. My head was spinning and my stomach churning. I let Amy deal with the registration necessary to get gas, as I grudgingly pushed the bike to the pump. The day’s adventures at a close, the adrenaline was subsiding and altitude sickness was settling in.

We headed a few hundred meters down the road to a guesthouse of sorts. We had expected some sort of traditional Tibetan lodgings. Instead we found temporary, container-like housing that seemed to have been hurriedly slapped together to give passing truckers a place to sleep on their way to Lhasa. We were shown a small 3 by 3 meter room with an ill-fitting door, where I curled up in my sleeping bag anxious for some rest.

Between the raucous card playing of the other lodgers outside and being woken up by brutal migraines, it was a rough night. Luckily though, what sleep we did get helped to placate the altitude sickness. Amy’s stomach still hadn’t settled, but I hadn’t had a full meal in 36 hours and forced my way through some noodles for breakfast while we chatted with our hosts.

A Tibetan woman strolls through a small village 300 kilometers from Lhasa

As it turned out, the middle-aged couple that ran the guesthouse were originally from Beijing. They had been coming out here seasonally, six months at a time, for the past couple of years. It was hard to understand why they chose to come so far out to the middle of nowhere. Nevertheless, they seemed content and certainly appreciated the freshness of the air that stood in stark contrast to the smog back home in Beijing, a sentiment we shared, despite the distinct lack of oxygen.

The sun shone at the start of our second day on the G219 and the wind, as we rode through the valleys, helped keep altitude sickness at bay. The valleys were, simply, breathtaking; fortunately none of the passes were as difficult as the day before.

We were taking a break at the foot of some hills when threatening clouds looked to be crossing our path. It started to get darker and the road looked like it was slick with oil, likely the result of a recent downpour that had darkened the asphalt. It wasn’t until we drove through an eerie section of road that was covered in dozens of mini ice-tornadoes, as clouds of snow and ice were being whipped around on

the slick pavement, that I knew we were in for some severe weather.

We kept our heads down, trying our best to bear the blizzard like conditions as best we could. Stopping was futile, a minute of rest just meant one more minute in the storm. Snow was violently coming down all around us. Visibility dropped to less than a car’s length, and I stayed behind our guide’s Mitsubishi 4×4, keeping my eyes fixed on his taillights, sticking to the path its wheels were leaving in the thick snow.

When we got through it, we hadn’t even realized we had crossed the border into Tibet. Another 20 days of conditions like this…It was hard to imagine being able to manage for that long.

Each morning we would wake from fitful sleep, fighting through altitude induced headaches, dreading the prospect of having to endure more snowstorms, but it turned out we had made it through the worst. Having made safe passage across the Tibetan border, the skies stayed clear from then on, opening up into a rooftop of pure, uncorrupted blue.

White pagodas outside a temple and beneath blue Tibetan skies

We spent days riding across the plateau, winding through valleys surrounded by towering mountain ranges. It was the colors in the region that struck me most—as if the contrast on a television screen had been turned way up, each distinct shade of green, yellow, turquoise, and blue stuck out prominently against the gray mountain backdrop. As if to emphasize the countryside colors, every pass we went over, traversing between valleys, was marked by towering tepees constructed entirely of multi-colored prayer flags.

We spent several nights in somewhat more traditional guesthouses. Though they all catered to tourists, we usually stayed in small villages on the road, each with their own Buddhist temple sitting on a neighboring hill. Some of our rooms even had their own heating stove. These stoves would be fueled by dried out yak paddies, easily the most plentiful energy source in the region. Yaks are used for everything in Tibet, wool for clothing, meat for food, and, yes, even shit for heating. We spent one memorable night on the shores of a holy lake, Lake Manasarovar, watched over by the nearby monastery, sharing our guesthouse with a horde of Russians who spent the night strumming guitars, singing folk songs from back home.

Yaks rest in the sun near Mount Qomolangma

It was nearly a week of riding along the G219, running along the borders, first with Pakistan and then India and Nepal, before we made it to the turn off for Mount Qomolangma, also known as Everest.

It was supposed to be a relatively short trip to Mount Qomolangma, just 70-kilometer from the main road at Old Tigri to base camp. Our guide warned us that none of it was paved, but that wasn’t anything new for us after two months on the road. This was different: six hours later and we had made it through the toughest 70 kilometers stretch of road that we had ever encountered. Passing

through minefields of fist-sized rocks and dodging ultraaggressive Chinese tourists in 4×4s left us exhausted and praying our bike would stay in one piece.

The area where you can stay overnight is not at the actual base camp, which, twice a year in May and August, is swarming with climbers from all over the world, setting up for a shot at reaching the summit of the earth’s highest peak—the rooftop of the world. In September though, it was all tourists making the pilgrimage to catch a glimpse of the peak, which, unfortunately, was shrouded in cloud when we arrived. Our camp was a small makeshift town; sleeping and cooking tents were set-up in a rectangle around the parking lot where you could find accommodation for the night and catch a shuttle up to base camp four kilometers away.

The six hours that it took us to make our way from the main road meant that most of the camp was full when we got there. The spot found was thanks to Ciren who sweet-talked one of the young Tibetan girls that ran a tent, getting her to offer us a place in the back, beside a makeshift kitchen. We followed her through the tent with our gear in tow and laid our sleeping bags on the bed, a wide, wooden sleeping platform large enough for a small family.

I had trouble sleeping again that night. We were at an altitude of 5,000 meters and the exhaustion from the relentless riding had brought on a persistent headache preventing me from falling asleep. Drinking enough water was difficult since the main drink available was usually tea.

Dozing in and out of sleep I heard music playing outside, accented with occasional hoots of excitement. I assumed it was just some noisy tourists from one of the larger buses that were having a late night and tried to sleep through it. My headache had other plans, and I got up to find a bathroom.

Outside was not, in fact, a bunch of drunken tourists; the music playing was actually Tibetan, a weird mix of traditional folk and electro-pop. A circle of people, some even held glow sticks, danced in the night, like it was some kind of mini-Tibetan rave. They were all dancing around the circle together in a synchronized rhythm to the music, swinging their arms and legs, and every now and then giving a loud “whoop whoop” when the moment felt right.

I ran back and pulled Amy out of bed. It was amazing to me. These were staff from various guesthouses and probably some guides too. It was past midnight, and these people had been working since six or seven in the morning, putting up with demanding tourists for the past 17 hours. Yet here they were, under a full moon, dancing, smiling and letting loose, full of energy—a Tibetan dance party at the foot of Mount Qomolangma.

The next day, we were woken before dawn by Ciren running into our tent yelling “Mr. Buck! Mr. Buck! Come! You can see! You can see!” Through our early morning grogginess it was hard to put together what he was saying. After we had crawled out of bed, our drowsiness slowly melting away, we ran to see what all the fuss was about: the clouds had cleared and Qomolangma was saying hello.

We made our way across the lot and joined with the small pack of people making their way out into the valley to catch the mountain in all its majestic splendor. A gaggle of amateur photographers set up their tripods for long exposure shots of the mountain as the glaciers on the north face started to catch the early morning light. Often people end up waiting for days at base camp before the mountain comes out from the clouds. We were incredibly lucky to get such a clear view during our short stay.

Standing there at the base of Mount Qomolangma it was hard to imagine how far we’d come to arrive at this point, and even harder to think about how much farther we had to go. Only a few weeks previously, a month after leaving Beijing, we were stuck in a two hour long sandstorm in the Turpan Depression, the third lowest inland place on earth. Now, after fighting snowstorms, bitter cold, and severe altitudes, we were standing watching the sunrise over the rooftop of the world.

Tibet was only 12th of the total 33 provinces we were to visit. Standing at 5,200 meters, it was fair to say it was all going to be all downhill from here. Yet, with ancient Sichuan, the island province of Hainan, the mystical mountains of Guilin, and so much more to look forward to, I knew there were going to be many more highpoints on our journey. After two months on the road, we knew there would be many more tough challenges on the way, but they were part of what was making this remarkable experience so amazing; we couldn’t wait to see what was next.