For the criminal in us all

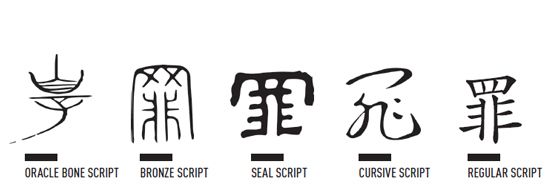

The human impulse to break the law has been around since law began, and in ancient China, the price paid was brutal. The lethal injection of today is lenient compared to the age when the character 罪 (zuì) was first scripted. When it was carved as bronze script during the Warring States Period (475-221 BCE), the character consisted of a nose-shaped radical on the top and a knife-shaped radical on the bottom, 辠, meaning punishment by “cutting one’s nose off ”.

As one might imagine, with such a vicious punishment, anecdotes abound. During the Warring States Period, in the royal court of the Chu State, Zhen Xiu was the most loved concubine of the king, but her striking beauty was matched by her sadistic temperament. When the king took a new concubine from the State of Wei, Zhen became jealous. Feigning friendship, Zhen offered the new concubine advice on how to keep the king interested. “His majesty doesn’t like your nose. You should cover it in his presence,” she said. The gullible new concubine then covered her nose with her sleeves every time she was visited by the king. After a while, the king, baffled by such a gesture, consulted Zhen: “Why does the beauty from the State of Wei cover her nose whenever she’s with me?” Zhen replied: “I’m afraid she is disgusted by your majesty’s body odor.” Hearing this, the king was furious and ordered the beauty’s nose cut off, putting Zhen once again in her lord’s good graces.

In most cases, the punishment of cutting off a criminal’s nose—or just branding their face—was not just to inflict pain; rather, it was to mark the person as a criminal, permanently. As such, the name of this particular punishment began to represent the concept of crime in general. Because the original character took on the meaning of crime, the original punishment was represented by a newly created character, 劓 (yì).

Later, when the Emperor Qinshihuang founded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), he called himself “the Initial Emperor” (始皇帝 shǐhuángdì). It was said that he found “辠” resembles “皇” (emperor) in shape and ordered it to be abandoned. As a result, a new character, 罪, was created to represent crime. Consisting of 网 (wǎng, web) on top and a phonetic radical, 非 (fēi), on the bottom; the character lost its original pronunciation, but it maintains its original form today. This new form indicates that, when one commits a crime, they will be quickly captured in a web.

Whenever you see 罪 in a word or phrase, expect the worst. Committing a crime is 犯罪 (fànzuì), and when you swap those characters, you get “the criminal”, which is 罪犯 (zuìfàn). A criminal charge is 罪名 (zuìmíng), such as 诽谤罪 (fěibàng zuì, libel), 盗 窃罪 (dào qiè zuì, larceny), 杀人罪 (shārén zuì, murder), and many others. For murders, you can say their crime is most heinous with 罪大恶极 (zuìdà’èjí) or describe them as 罪孽深 重 (zuìniè shēnzhòng, deeply sinful). In fact, 罪 stands for both the religious concept of “sin” and the legal concept of “crime”. A sinner is 罪人 (zuìrén) while 罪孽 (zuìniè, sin) always carries the meaning of retribution. When it comes to punishment for extremely vicious crimes, many believe 罪不容诛 (zuì bùróng zhū, even ending their lives won’t make up for the loss), or 罪 该万死 (zuì gāi wàn sǐ, worth dying ten thousand times).

When the police crack a case, the culprit is called 罪魁祸首 (zuìkuí huòshǒu, literally, the chief of the crime and leader of the disaster) if you want to be dramatic about it. Evidence of a crime is 罪证 (zuìzhèng). And, when a criminal is roundly punished, you can say 罪有应得 (zuì yǒu yīng dé, a punishment well-deserved). In some cases, criminals can exchange testimony and service for a lighter sentence, which is called 立功赎罪 (lìgōng shúzuì, performing meritorious service to atone for one’s crimes).

In some cases, 罪 means misconduct and mistakes, such as in 归罪于人 (guīzuì yú rén), which means “to blame other people for mistakes or negative results”. The character also means “pain and hardship” as in 受罪 (shòuzuì, to suffer from pain and hardship). You can also use the word in unpleasant or uncomfortable situations, for instance: 他晚上打呼噜很厉害,跟他住在一起真受罪 (Tā wǎnshàng dǎ hūlū hěn lìhài, gēn tā zhù zài yīqǐ zhēn shòuzuì, he snores heavily; to live with him is such suffering). Or it can be used in this context: 她看电影总喜欢哭,跟她一起看电影简直是受罪。(Tā kàn diànyǐng zǒng xǐhuan kū, gēn tā yī qǐ kàn diànyǐng jiǎnzhí shì shòuzuì, she cries a lot during movies; to watch with her is such suffering.)

This character follows crime from the deed to the jailhouse and is indelibly linked to a less forgiving time in Chinese history. From lopped off noses to insecure emperors and from murders to mistakes, 罪 is a character one doesn’t often look forward to seeing.