A chilling look at China’s mass murderers and the world around them

This year, as millions across the country were readying for the Spring Festival mass migration, 36-year-old Li Hao was preparing for his final journey.

On January 21, the former fireman was strapped down before being injected, in orderly fashion, with barbitone, a short-action anesthetic barbiturate, followed by a muscle relaxant of pancuronium bromide and, finally, potassium chloride, which finally stopped his heart for good—thus carrying out the sentence that had been handed down in 2012 for crimes that included multiple murder, rape, kidnapping, prostitution, and illegal imprisonment.

But it was a bizarre, and some might say uniquely Chinese, series of events that eventually led to the headlines in 2011 revealing how Li, then 34 and enjoying the lifestyle of a mid-level drone at the local Technological Supervision Bureau, had spent the last 22 months cruising karaoke bars in Luoyang picking up victims, while telling his wife he was moonlighting as a part-time night watchman.

In fact, there was a macabre truth to Li’s claim. He had, indeed, been keeping watch—albeit over a harem of kidnapped KTV hostesses aged between 16 and 23, held captive in a remarkably sophisticated prison, constructed four meters under a rented basement and locked behind seven iron doors.

In this subterranean kingdom, shut off from the outside world, the civil servant apparently exerted a compelling influence over the six women, who called him “Big Brother” and competed for his affections and sexual favor. Li, meanwhile, kept his victims weak through lack of food and water and occasionally tortured them for gratification, police say. Anyone who resisted was raped; two girls were put to death for “disobedience”.

Huang Yong, charged with murder of 17 boys but believed to have

killed many more, faces trial

Eventually, Li progressed to staging “pornographic web shows”, acting as both producer and gaoler. Seeing an opportunity to make more money, Li even progressed to pimping, which proved a fatal mistake: one of the women was left alone long enough to make a bold escape. A relative later went to the police—who set about dealing with the matter as discreetly as possible.

Li was swiftly caught attempting to flee the city, and his extraordinary crimes and punishment might ordinarily have warranted a few terse statements somewhere in the Luoyang Evening News. But, a remarkable confluence of events would ensure the opposite. In the same September that Li Hao made his ill-fated flight, journalists from around China had gathered in Luoyang, drawn by the highly publicized case of Li Xiang, a TV journalist investigating so-called “hogwash” gangs. The gangs were selling recycled, toxic cooking oil dredged from gutters,and police claimed to have cracked the case.

Li Hao’s case was hardly exceptional—his deeds mirrored those of Zeng Qiangbao, a 39-year-old Wuhan janitor who received a suspended death sentence in 2010 for imprisoning and torturing a pair of 19 and 16 year olds for months; however Luoyang officials were pushing a Civilized City campaign and that meant stamping down on negative publicity even harder than usual.

After the reporter announced on Weibo that he was “following illegal cooking oil dens closely”, Li was found dead outside his apartment in the early hours, with 13 stab wounds. Police subsequently charged two local ruffians with robbery and murder. A botched mugging—or was there a conspiracy to silence the press, as others wondered. Had someone taken the crackdown too far? One who suspected so was Southern Metropolis Daily’s Ji Xuguang, a journalist from a powerful media organization outside Henan with a reputation for bold muckraking. Ji was still looking into Li Xiang’s death when he picked up a lead on the (far more sensitive) Li Hao story. Henan police, keen to put him off, threatened Ji with the serious crime of revealing “state secrets”—so Ji simply left Henan.

Thanks to Ji, the resulting story of the Chinese man who kept his victims in a secret torture dungeon would make headlines worldwide, just as the Cleveland kidnapping case would in 2013. Had local authorities had their way, however, the scandal would have disappeared from view, like one of Li’s KTV girls.

“People don’t care much,” says Li Qiaoying, a former criminal psychology researcher with the Taiyuan Procuratorate in Shanxi. “Even in a village where a newcomer used to get attention, nobody nowadays cares…People only look after their own business.”

“I picked prostitutes as my victims because they were easy to pick up without being noticed,” explained 54-year-old Gary Ridgway, or the Green River Killer, after the Seattle serial killer was finally brought to justice in 2003. They may as well be the words of Li Hao—or Wu Jianchen, a serial rapist who killed 15 in Hebei in 1993; or Li Shangxi, Yang Mingjin, and Li Shangkun from Guangxi, who killed 26 between 1981 and 1989; or Peng Miaoji who murdered 77 across Shanxi, Jiangsu, Anhui, and Henan, executed in 2000; or Yang Shubin, who was tracked by one resourceful police officer for eight years, following a trail of robbed and murdered KTV girls from Shenzhen to Guangzhou to Jilin, finally ending in Baotou, Inner Mongolia, where Yang and his gang had used their millions in blood-soaked RMB to set up a family-run massage business.

During the early to mid-20th century, when its serial-killer population exploded, America was a developed country engaged in rapid urbanization: densely packed slums became populated by anonymous migrants in constant fl ux, and its cities interspersed with vast tracts of deserted land—running throughout and serving as newly built getaway conveniences with highways and railroads. This helped birth the kind of shadowy, itinerant killer for whom anonymous and transitory existences are their fodder: the crosscountry trucker with a penchant for making friends at deserted rest stops, the mooching outlaws of In Cold Blood crawling through small towns in a stolen car and scouting for victims.

In the early 1980s, China underwent its own period of rapid industrialization, truncating over a century of American-style urbanization into just a few decades. Crime experts now point to the period of Reform and Opening Up as a time when society fragmented, communities scattered, and itinerant workers and criminals flourished.

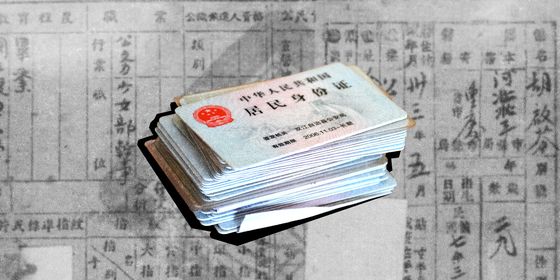

The hukou [household registration] system, which had previously kept people strictly rooted in place, was relaxed and, frequently, simply overlooked; strange people appearing in the neighborhood no longer seemed strange. “The police don’t have effective control of who was in their district doing what,” says Yin, a criminologist from the University of Politics and Law who asked for his real name to be withheld. Disappearances are just as common: a migrant might go home, marry a villager, or have to deal with a family matter. They get a better job—or perhaps, if they’re a sex worker, their client wants a full-time mistress to himself. “Even parents don’t really know what their children are doing in the city or where they live,” says Li Qiaoying.

Then there are other potent ingredients, such as poor education in rural areas that leave many even unaware of such crimes. During 2012, a small county in Yunnan was traumatized by the disappearance of 17 young men. Local parents had fingered a plausible motive: the boys were being kidnapped and forced to work in illegal brick kilns near Kunming. Such kidnappings are not uncommon in the provinces, such as the case of Lei Yusheng, a Yunnanese boy who was snatched at knife point and forced to work with 30 other abductees for 10 hours a day.

April in 2010, Zheng Minsheng, who stabled eight students, was sentenced to death

This led some parents to pursue their sons’ fates in the hundreds of illegal kilns that dot the province—a diffi cult and dangerous task in itself—and one which police have little time for. What these anxious parents were not to realize was that their sons had actually fallen victim to an Ed Gein-like predator called Zhang Yongming, who lived a hermetic existence nearby in a shack filled (according to later-deleted mainland articles and Hong Kong media) with bags of bones, dried human flesh, and wine bottles filled with preserved body parts. Although the disappearances had been going on for months and although Zhang had a murder conviction from 1978, police never saw fit to investigate him.

Zhang himself was considered more a local oddball than a serious suspect despite his criminal past. An incident involving Zhang in 2011 gives a small window into the treatment of mental illness in the country: Zhang was caught strangling a 17-year-old youth outside his house with a belt but “laughed off the episode, saying that he was just fooling with the boy”, the media later reported. Only after a year of killing was Zhang caught.

Mental illness remains a closeted topic in China; neither medication nor modern psychiatric treatment is widely used and a 2010 analysis in British medical journal The Lancet estimated that 91 percent of the 173 million Chinese adults suffering mental problems receive no professional help whatsoever. Li Zhanguo, who targeted 11 men with severe learning difficulties between 1991 and 1995, is a different example of how China’s attitude towards mental healthcare can be exploited by villains: Li successfully counted on police and victims’ families to blame their disappearances on their illness.

To read the rest of this article, buy the Crime issue in our online store or our Taobao store today!