The sacrifice of the Chinese Labour Corps

In the tiny French commune of Noyellessur-Mer, facing the English Channel, a stone Chinese archway rises incongruously at a cemetery entrance. Inside, over 800 graves are marked with Chinese names, birthplaces, death-dates between 1916 and 1920, and Biblical phrases in Chinese and English.

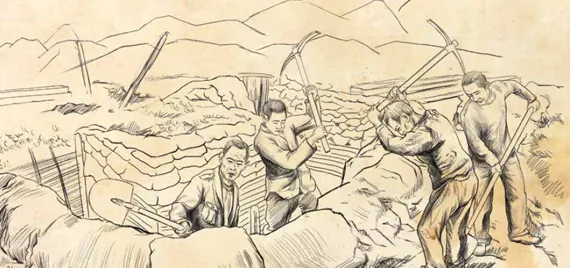

The dead of Noyelles came from the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC), a force of 100,000 Chinese who, from 1916 onward, dug many of the trenches that criss-crossed war-torn France. The British-led CLC, and another 40,000 men working for the French, carved out defences, built barricades, fixed railways, and mended telegraph wire. The Chinese Labour Corps was the creation of wily Chinese statesman Liang Shiyi (梁士诒), once the technophile Minister of Railways under the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911). It was an attempt to get on what he saw as the winning side of the war and ultimately better China’s place. Germany, like the other Great Powers, held considerable concessions in China, and siding with the Allies, even if only quietly at first, would position China to reclaim those colonies at war’s end.

It was appropriate enough, then, that the majority of the laborers he negotiated to send to France were from Shandong, where the German concessions were sited. The British and French officials involved in negotiating the contracts were looking for strong Northerners, and the men were said to be often “six feet tall”, a striking height at the time.

The legal status of the laborers was somewhat dubious; as, officially, a non-belligerent China could not supply military aid to the Allies without violating its neutrality. The Germans protested against the creation of the labour corps to the Chinese government, which replied by specifying that this was a purely civilian deal, handled through a conveniently created “private company”, the Huimin Company, and if this supply of labor happened to be used for martial purposes, that was nothing to do with them. That the Huimin Company had been brought into existence by Liang Shiyi purely for this purpose was not allowed to trouble this legal fiction. The laborers themselves have left little record. Almost entirely illiterate, their histories were set down by others, whether the British officers who dealt with them or the educated Chinese who accompanied them as translators. Farmers and migrants from rural villages, their transition into the war was also a transition into modernity.

As they entered “the sausage machine” of processing, their traditional queues were chopped off; they were washed, fingerprinted, and given a number,not a name. In his book, Strangers on the Western Front, Guoqi Xu demonstrated why this mechanistic process was made necessary; in the book, a British officer is recorded saying, “The man didn’t know his own name. If you questioned him, he’d say ‘Well, I come from the Wong family village, so my name is probably Wong.’ You’d say, ‘All right, well what is your personal name?’ and he’d grin and say ‘Wong’. We’d say, ‘Well, what are you called at home?’ and he’d say ‘Well, I’m known as Number Five, or Little Dog, or Big Nose.’

But the conditions were praised by the workers, who enjoyed the food, the hot baths with soap, and the clean housing. Even shipped in crammed holds, or in packed railway carriages across Canada, they remained, according to their supervisors, cheerful and practical, “the finest lot of men I have ever seen.” While they were often the target of racism from locals who had little contact with them, and from a military hierarchy that sometimes treated them like prisoners, locking them away in camps when off-duty, soldiers and officers who worked alongside them were full of admiration. They dug an average 200 cubic feet per day,compared to 140 for a British worker.

And like the soldiers around them, they died. They were killed in artillery shelling, as they dug embankments or strung wire under the fire of German guns. They were killed by snipers, unable to distinguish civilian workers from Allied soldiers across the haze of No-Man’s-Land. They were killed by German soldiers unable to make fine distinctions in the angry fury of breakthroughs into the enemy’s trenches. Most of all, they died of disease, coughing and spluttering their last in the great wave of post-war influenza, which slew more worldwide than the war itself.

Traditional Chinese belief valued being returned to one’s birthplace so highly that an entire profession of “corpse-walkers” existed who would single-handedly, and literally, walk dead men back to their hometowns. But there was neither the knowledge nor the infrastructure in place to send corpses back to Shandong. Instead they were buried among the rest of the Allied fallen, clustered in tens or twenties in some places, or not commemorated at all. The first that a distant wife, now widow, might hear of it was when a payment stopped or comrades returned, with the absent presumed dead.

Just how many of the laborers died is a matter of contention. The official Allied total was just under 2,000, but this is certainly an underestimate. Some Chinese academics have placed the total at 20,000, but more out of a need to emphasize China’s contribution and suffering than out of actual evidence. Likely numbers may be around 8,000 to 10,000.

Liang Shiyi’s dreams of Chinese rejuvenation at the expense of a beaten Germany did not come to fruition. Although China officially joined the Allies in 1917, it never sent soldiers, since the war ended before a proposed expedition force could be sent. Instead those men were sent to Mongolia, which had declared independence in 1911, in a brutal and futile attempt to reimpose Chinese rule that ended in ignominious defeat by the White Russian warlord,Roman von Ungern-Sternberg.

And in one of the most short-sighted and toxic moves of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 (and there were many), Japan, busily engaged in trying to reduce China to its colony, was granted Germany’s former holdings. Chinese students erupted, fanning the flames of the country’s revolutionary ideologies and newfound nationalism.

Of the CLC, around 3,000 stayed in France, where they became part of a Chinese presence that would provide an intellectual home for hundreds of influential figures, from Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) to Ho Chi Minh (胡志明). Tens of thousands returned to their hometowns with strange tales of foreign lands, corpses strung on wire, and the rattle of machine guns. In the next decade, after the Republican government collapsed and the country was split among warlords, these memories became all too practical.