How the prostitution of the past wrote some of China’s greatest poetry

Prostitution is oft cited as the oldest of professions, but is it possible that it might just be the most noble as well? Today, we view prostitutes, typically, as women who engage in sexual activity for payment. However, back in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), a modern man would be astounded by the brothels of the day and the women living in them; modern interpretations simply fail to grasp the complexity of the “prostitute” of yore. Our sexual time traveler would find an artistic trade that transcends the simple and tawdry exchange of sex for money.

For a long time in ancient China, prostitution was completely legal. As scholar Lin Yutang (林语堂) wrote: “One can never overstate the important roles Chinese prostitutes played in romantic relationships, literature, music, and politics.” The contradiction between the modern and the ancient concepts of prostitution in part comes from the origin of the word itself. The Chinese character for prostitute, 妓 (jì), is not so much to do with sex but instead “a female performer”. These women did not just offer sex but rather the pleasure of their company through music, singing, dancing, and even poetry.

In ancient China, noble ladies did not need to be intelligent or talented to be respectable, and ancient China, for all its delicate charms, could be hard on women. A proverb first seen in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) book The Elders Thus Say (《安得长者言》), is frequently quoted describing the ideal woman: “A woman is virtuous as long as she is ignorant.” The Chinese woman is supposed to be obedient to her husband, dutiful to her children, mind her domestic affairs and be virtuously

ignorant on all other matters.

As wives and concubines were expected to abide by social codes, Chinese men were in need of intellectual counterparts of the opposite sex. Marriages were matters of social hierarchy, leaving endless scholars and aristocrats with marriages that lacked both the affection and communication that can be found on a deeper, more spiritual plane. Prostitutes were exceptions to the rule. Unlike the girls brought up in ordinary families who were deprived of education, prostitutes were taught to become—not merely entertaining performers—but the mental equals to aristocrats, scholars, government officials, and all manner of high society.

As the Dutch sinologist Robert van Gulik observed in his 1961 book Sexual Life in Ancient China, when Chinese men courted prostitutes they were more looking for a friends with benefits type scenario, sometimes not even requiring sex at all. By enjoying the company of these skilled, entertaining, and intelligent women, they could escape from their sexual obligations to their wives and concubines, as well as the dull atmosphere of their homes. Flipping through The Complete Poetry of the Tang (《全唐诗》)—one of the most colossal compilations of Chinese poetry—reveals the influence of prostitutes upon Tang Dynasty culture. Of the 49,000 poems, over 4,000 are related to prostitutes and 136 were written by prostitutes themselves.

Prostitution flourishing in the Tang Dynasty was probably due to the founding of a new governmental administration called jiaofang (教坊)—literally meaning “The School”, but “conservatory” may be more exact—a high-end finishing school for girls. They trained in music and dancing as well as literature, calligraphy, and a host of other highbrow entertainments such as chess and literary drinking games. The jiaofang system lasted several centuries, at least until the middle of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911). The prostitutes trained in jiaofang were called “official prostitutes” and provided entertainment for officials and scholars alike. In Chang’an, these registered prostitutes usually needed to have at least one excellent quality to establish their fame; dancing, singing, and literary talent were all highly revered skills.

Rather than sex, brothels’ main income came from the holding of feasts. The madams running the brothels didn’t encourage the prostitutes to have sex with their guests as this would decrease their value, and, of course, the fear of pregnancy was ever-present. Sexual relationships usually happened with the prostitute’s consent, and she usually maintained only one sexual relationship at one time. If a man wanted to pursue a sexual relationship with a prostitute, he had to be careful; if it came to light that the prostitute had a major patron of high rank, things could get ugly.

The key to a prostitute’s popularity was usually not her body but her mind. In The Notebook of a Drunken Man《醉翁谈录》), a book by Song Dynasty (960-1127) writer Luo Ye (罗烨), the writer gives a faithful account of Chang’an’s biggest brothel, Ping Kang Li, and described in detail several of its more famous prostitutes and their respective characters. Interestingly, most of the prostitutes were not known for their beauty—some of them were even quite plainly described as being average looking. But, their intellect and poetry made them desirable.

Not everyone could afford the pleasures of these prostitutes; according to the writings of Song scholar Sun Qi (孙棨), the residence of a first-class Tang prostitute contained spacious halls, yards with artificial hills and ponds, and exquisitely decorated furniture. In his masterful essay “Prostitutes and Concubines” (《妓女与姬妾》 ), Lin Yutang wrote: “To approach those women was not as easy as it seemed. The men usually needed to spend months and even years in pursuit, squandering thousands of silver goblets.” Red light districts were a veritable who’s who of high-society, nothing like the seedy backstreets of today.

Aside from the upper-classes, young scholars made up the backbone of a brothel’s clientele. The Imperial Exam was held in Chang’an every three years, during which time young (and old) examinees flocked to the capital. The exam was a way for the government to screen officials, and passing it gave you the chance to acquire a comfortable administrative position as well as heightened social status. It was an unwritten rule that those who got the degree would throw lively parties in brothels. The Chronicles of the Tianbao Era (《天宝遗事》), a historic book on the Tang Dynasty, recorded a night in the Ping Kang Li brothel: “There you can find all the elite young men in town, and it is packed with scholars who have just excelled in the imperial exam, roaming around with their name cards.”

Poetry in the Tang Dynasty bore the same influence as the top hits in today’s music charts. A famous scholar’s poem could make or break a prostitute’s fame; A poet named Cui Ya (崔涯) was such a prostitute critic. “Every poem that he wrote about a brothel would immediately spread in the streets and alleyways in town. If it was in praise, then the prostitute’s gate would be lined with carriages and horses; if it was negative, then the prostitute would be so panicked that she couldn’t eat or drink,” wrote Tang Dynasty scholar Fan Shu (范摅) concerning Cui Ya’s authority. In short, Cui Ya knew his prostitutes. The poets’ relationships were, in many ways, symbiotic. The prostitutes served as the perfect muse for the poets’ writings, and the poetry allowed both to find fame. With that, the intimate relationship between poet and prostitute blossomed.

Like Cui Ya, Liu Yong (柳永), a Song Dynasty (960-1279) poet, spent his entire lifetime writing poems for prostitutes; unfortunately for Liu, his fame as a poet was so great that it backfired, crushing his hopes of becoming an official. When the well-known young man took the Imperial Exam and passed all the tests, the emperor rejected him, saying: “What do you need feats and fame for? You should just fill your cup and softly sing.” As a result Liu gave up all hope of become a politically-accomplished man and spent all his time and talent writing odes to the prostitutes with which he was so enamored.

Liu intimately befriended the finest prostitutes of his era, finally finding himself impoverished and living off the financial aid of others. He died penniless but not friendless. Dozens of his prostitute “friends” funded his funeral. According to the Ming novelist Feng Menglong (冯梦龙), on the day of his funeral, “The whole city of Chang’an was dressed in white as his funeral procession was followed by all the prostitutes in town. The ground quivered with their mourning voices… For years to come, on every Tomb Sweeping Day, famous prostitutes would visit his grave and hold ceremonies. Those who didn’t attend the occasion would be too ashamed to appear for the spring excursion.”

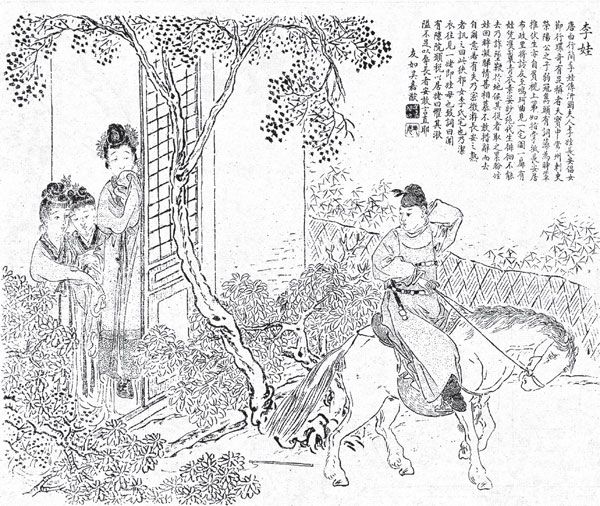

Li Wa (李娃), a Tang Dynasty prostitute, flirting with a guest in her residence. Portrait by Wu Youru (吴友如), a Qing Dynasty painter

If Liu and Cai were Lennon and McCartney, then Bai Juyi (白居易) was unquestionably Elvis. Bai was a poet in the Tang Dynasty who also achieved fame for his friendships with prostitutes, with over 100 prostitutes mentioned in his poetry. His best known poem records his encounter with a prostitute on a boat. The poem, aside from its unerring literary virtue, reveals the typical life of a prostitute. On a misty, cold autumn night, Bai was attracted by the delicate sound of a four-stringed lute known as a pipa while he was feasting by the river of an obscure town, knowing it must have been played by a prostitute from the capital city. He sought out the girl, and she told her story.

She was the best student of the pipa masters in Chang’an, and in her younger days she was the belle of society, heralded near and far. “The moneyed youths vied for the chance to present me brocades, and I receive numerous silks every time I finished a song. Combs mounted with gems were shattered beating to the rhythm, and many a time, spilled wine stained my scarlet skirt.” But the carnival couldn’t last forever, and, like all great beauties, she became old. Like many of the prostitutes of the time, she married a merchant. Her husband was seldom home, and she ended up playing her pipa alone on a boat. Bai sighed, “We are both roaming souls in this world. Now that we’ve met, there is no need for us to know each other.”

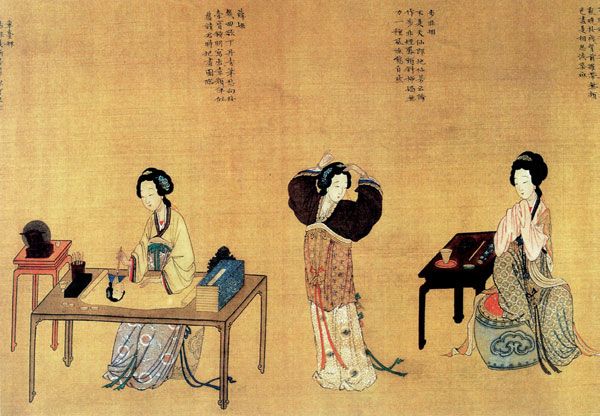

A portrait of Xue Tao (far left) by an anonymous Ming Dynasty painter

The connection between prostitutes and poetry didn’t stop at appearances in the poems of males fawning at their feet; many were gifted poets themselves. The most famous was Xue Tao (薛涛), a government official’s daughter who was educated in poetry and painting as a young girl, and by the age of 15 she was already widely-known for her poetic talent. Unfortunately, her father died when he brought his daughter to Sichuan, leaving Xue Tao in financial hardship. She registered herself in the

jiaofang as an offi cial prostitute and, undoubtedly, made the best of the career. She hosted celebrities—from revered scholars to high offi cials—and exchanged poems with almost all the important poets of her time.

Even her residence became a tourist spot. If a man of decent social rank went to Chengdu without visiting Xue Tao, he would be embarrassed to say he had been to Chengdu at all. For most of her life she had been financially supported by Wei Gao (韦皋), a military general and the governor of Sichuan Province. On his death, Wei Gao left her a significant fortune, and she resigned herself to a quiet life by Washing Flower Brook near Chengdu, eventually dying at the ripe, old age of 73. Today there is still a park in Chengdu containing a pavilion where Xue is reputed to have contemplatively looked over the river.

Xue’s contemporary, Yu Xuanji (鱼玄机), was another legendary poet, but had an altogether different tale to tell. Like Xue, Yu was known as a genius poet in her youth and wrote of her envy for men in a poem, “I resent this skirt that hides my poetry, and in vain I envy men with degrees.” She was married to the scholar Li Yi (李亿), as his concubine. However, Li couldn’t handle his fi rst wife’s ferocious jealousy, so, to protect Yu, he sent his mistress to a Taoist temple to meet with her in secret. During the Tang Dynasty, a Taoist temple could have very irreligious connotations. When Emperor Xuanzong (唐宣宗) visited a Taoist temple, he was astounded and enraged by the “nuns” wearing heavy make-up and dressed in bright colors who were obviously not living the chaste and secluded life that was expected of them.

In the Tang Dynasty, 21 princesses became Taoist nuns, and they were known for their extravagant way of life in the temples, with no abstention from wine, partying, or men. For women who felt displaced as wives or concubines, Taoist temples were a haven, and with Yu Xuanji’s talents and libertine ways, she remained there. Li never returned.

She had many sexual affairs, and her love poems were seldom addressed to the same man. However, she was later accused of whipping her maid to death—accusations that are likely false—and was executed at the age of 22. Her poems are still alive, displaying her liberal, individualistic nature and, ultimately, she received far greater critical acclaim than her contemporary Xue Tao. Today, academics hold her up as an early feminist icon.

By the Ming Dynasty, prostitutes’ social statuses had marginally changed. They could attend scholars’ meetings and even called themselves “brother” in their correspondence. Liu Rushi (柳如是) was a prostitute who lived during the transition of the Ming and Qing dynasties—one of the most independent figures in the history of Chinese women. When she wanted to make the acquaintance of Qian Qianyi (钱谦益), a famous scholar, she eschewed traditional gender roles and simply bought a boat to travel to see him on her own. She dressed herself in men’s clothes, and according to her biographer, Shen Qiu (沈虬), “carried an air so elegant and frank that she might as well have been a hermit.” Qian fell in love with her when he read her writings and eventually became her husband. Liu was also a fervent patriot who refused to surrender to the reign of the Qing government and involved herself in anti-Qing actions for most of her life.

The Qing Dynasty brought with it, however, the death of the jiaofang, and as modernization progressed, prostitutes with noble talents became increasingly rare. Thus, perceptions began to change: it became common to make fun of prostitutes’ illiteracy and their clients’ vanity. The business of prostitution became greedier, and sex as a commodity took the place of the fine and honorable ancient Chinese prostitute. By the Qing Dynasty and right through to today, the noble art of prostitution has been in decline—making them little more than objects of men’s sexual desires. They are no longer seen as having great minds, being supreme dancers, pitch-perfect singers, or enchantresses who both write and are revered in the finest poetry. For all the barbarism of those bygone days, perhaps the tale of the ancient Chinese prostitute is one that modern man can take to heart.