Parkour pounces on the walls and ledges of Beijing

They’re like today’s superheroes, scaling walls, jumping off buildings and defying gravity. To the rest of the world, it’s called parkour, but in Chinese, it’s called paoku (跑酷). The phrase literally translates to “cool running”. Not to be confused with the film Cool Runnings, the phrase means: “Hey man, those are some cool kicks.” The origins of the sport trace back to France in 1988, where it was started by David Belle in Lisses, a Parisian suburb. Inspired by indigenous people on a trip to Africa with his father, he watched their movements as they interacted with their surroundings to transport themselves from one place to another, using would-be obstacles and turning them into instruments to move their bodies forward.

When Belle returned to France, he and some friends developed the sport’s techniques and further enhanced their athleticism, becoming the first traceurs and traceuses (male and female parkour practitioners respectively) .

Although no single event can be cited for the entrance of parkour into China, it is commonly agreed that the sport arrived in 2006. Co-founder of the parkour magazine, BreathePK, Matt Talbot-Turner was in the tiny town (by Chinese standards) of Jinzhou, Liaoning Province for two years, practicing parkour in 2004 and 2005—way before it hit the mainstream. He doesn’t hide the fact that he had a tough time going about it back then.

“Practicing in China was difficult for me because there was no structured community to join. No gyms or groups. And because most people still didn’t know what it was. Jumping off of buildings and structures was frowned on by a lot of people that encountered me doing it.”

The sport grew quickly after 2006, but in China, back-flipping, villain-fighting heroes were nothing too out of the ordinary. Chinese culture already had wushu (武术), wuxia (武侠) and kung fu; forms of martial arts that—at least in the television shows—already demonstrated flying fight scenes.

“I don’t know for sure how it began but I’d imagine it began like a lot of other places. Gymnastics, martial arts, tricking, and dancing were already present in the community and therefore a form of parkour already existed,” Talbot-Turner explains.

After moving to southern Guangzhou and fastforward almost a decade later, Talbot-Turner looks at the parkour scene in China and says definitively that parkour in China is about to explode. One benefactor of the parkour popularity boom is 21-year-old Cheng Wei. Cheng had been practicing kung fu since he was a little boy before he began training with Parkour Commune, one of the two parkour teams in Beijing. “I used to practice qigong (气功) too,” he says, “but now I like practicing parkour more.”

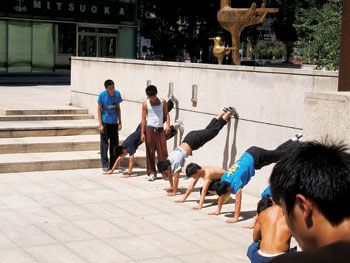

Parkour Commune, along with Urban Monkeys, make up the two big teams in Beijing. Gao Ke leads Parkour Commune, the team that Cheng practices with most Sundays in a plaza by The Place in Jintaixiqiao. The plaza is partly owned the by a Frenchman who enjoys and recognizes the growing popularity of parkour in China.

Gao’s unassuming stature hides his fit physique. A Jiangxi native, Gao first learned about parkour in 2007 after watching a video of David Belle, and has been hooked ever since. He has been practicing for about six years and now coaches people who want to get into the sport.

“In my opinion, parkour is first useful,” he says. “If you get into a dangerous situation, you can leave quickly and save yourself. Also, it’s useful for the body. You don’t need to go to the gym, you just train outside.”

“Lastly, it builds creativity. It requires more imagination,” he pointed out. “You can also learn about the connection of the human body and the building, the connection with the body and the city.”

As with most extreme sports, the issue is always safety first. After the death of a parkour enthusiast in the southwestern province of Sichuan in April this year, parkour has received negative attention as a foolhardy youth pastime.

“The first thing I tell a new person who wants to practice parkour is to keep safe,” Gao says seriously. When it comes to practicing outdoors, he admits, “The quality of the building may not be very safe. If Chinese built it, it’s not very good,” he laughed. “And check the ground, because you might step on something like broken glass.”

Weizi from the Parkour Commune backflips through Xizhimen

However, Gao states that it is your body’s internal balance that is most important. “If you feel pain, then your body has an imbalance. If you feel pain then train parkour, then you will absolutely hurt yourself… even if you have warmed-up well.”

“Some people have some imbalance in the body, then they train parkour… so they injure themselves. I think the basic step is that they should rebuild the body’s balance. It’s like if your shoulder feels pain, maybe the problem is here,” he says pointing to his foot.

“The body is a whole unit. You cannot analyze a problem and disregard everything else, closing it off to just one place. I always rebuild the body’s personal balance first. Then I always rebuild the movement pattern,” he says, listing things off with his fingers. “Then you can train for muscle endurance, then strength, and then power, speed, velocity, agility; then, finally, parkour technique.”

Still relatively unknown, but growing in popularity, Gao is concerned about the way parkour is developing. “The development of the parkour environment still has a long way to go,” he says. “First, Chinese people don’t know how to practice it (correctly) and they can injure themselves.”

Zhangjing Shuyu launches himself over a fence at the Beijing Jiaotong University

Gao points out that traceuses, or female parkour practitioners, are much more particular about safety: “Behind the CCTV building, I have another training class for girls. It’s safer, and I have more mats,” he says. “I think girls have more passion. Girls have more passion,” nodding and repeating the statement for emphasis. “If they come train parkour, they will train hard. They have more focus.”

Gao’s tone changes when the subject of competitions comes up. “My thinking is quite Chinese, but I think all things are shuangrenjian (双刃剑), a double-edged sword. It can help people and can hurt people,” he begins.

“If you have a competition, it will really spread the word about it and help people become aware of it. But if some people just know parkour as something in a competition, its really bad. Some young guys who just go into parkour to compete will end up hurting themselves.”

Sponsored competitions, such as the Red Bull National Parkour Tournament, haven’t had the easiest time breaking into the market. Beginning in 2009 and held again in 2011, the competition fizzled out before it could fully gain steam.

“Red Bull pulled out due to a partnership change with a major parkour group due to a poor working relationship,” says Talbot-Turner, though he refuses to name names. However, he is still optimistic about bringing other big events to the country.

“The Red Bull ‘Art of Motion’ (competition) currently runs in other parts of the world on a regular basis. My company would be very interested in bringing it to China and I think, with my experience living in China, we’d be the right ones to do it.”

Gao though remains unconvinced that the positive impact of competition outweighs the negative. “I think the first time I met them, I thought it was all for money,” he says bluntly. “I told the sponsor, you need more places to teach basic parkour techniques in the competition,” he added, citing the safety hazards in poor and untrained practice.

As an example, he cites the majority of the people he has coached over the years. “They will learn for about one to two months, then they will disappear. Of course, they will! They just know that parkour is about cool flips and some difficult movements. When they come here, they say, oh it’s just some basic training, then they leave,” he explains with a touch of regret in his voice. “Many people come and go; they disappear.”

Parkour practitioner Cheng Wei agrees. “The hardest thing about parkour is the most important: the basics. Lots of people think its no big deal, but it’s like a building with a bad foundation. The basics are the foundation and so you have to learn them well.” He adds after some thought, “You need the patience to make sure the condition is good.”

However, not everything is doom and gloom though for traceurs and traceuses with competitive spirits in China. “They (the sponsors) want to develop parkour, but they just have no suggestions, no method to develop and train,” Gao says. So in a best-of-both-worlds solution, he has teamed up with competition sponsors and the Chinese government and is in the works to further develop parkour in the country, hoping to bring adrenaline-pumping, death-defying stunts in a way that promotes safety.

The result is that Red Bull China is set to host their first ever tournament in Hebei Province in August. It will be a different competition from the Red Bull National Parkour Tournament that was run by its international team, though they will use the same name and hope to have it run on a yearly basis.

Just as well too, as it seems there’s no stopping the infiltration of parkour into the media. The increased exposure on the internet has attracted many who would otherwise be unlikely to try the sport out, such as 24-year-old Ou Langlang.

Ou has been training for a little more than a week but is keen on continuing the practice: “I wanted to learn because I like freedom!” he says with a smile. Shy, the Masters student in Transportation Engineering is hardly the muscular, adrenaline-junkie stereotype.

Ou found videos of parkour online of foreign traceurs and decided he wanted to try it himself. “I want to be able to go across any object to find a road to anywhere,” he says.

The Parkour Commune holds an open session, by coach Cui Jian, at The Place every Sunday

It seems that the future of parkour in China is full of possibilities, though there are a few key things that it still needs to really take off. Talbot-Turner states that, “the first thing it needs is a dedicated parkour gym. This would give it a home and a foundation for athletes to group around. Having a gym in place does wonders for building the community.”

Even Parkour Commune, Gao’s team, doesn’t have a dedicated gym. They sometimes practice in the Beijing Sports University when the frigid Beijing winter comes around.

And when it comes to spreading the good word of parkour, Gao has got it covered. His book, City Streets, was recently published in June, and details the body basics and parkour how-tos for curious traceurs/traceuses-to-be, educating them on how to practice correctly.

Talbot-Turner is also working with a local travel agency, The Young Pioneers, on a parkour trip to Beijing and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. The trip will bring traceurs and traceuses from all over Asia and North America together to an entirely new frontier.