Peter Chan’s newest blockbuster sparks nationalism in defending the Chinese Dream. But just what does it entail?

If Aaron Sorkin penned Chinese movies glamorizing the rise and fall of entrepreneurs in the 90s, then American Dreams in China surely would have been the jewel in his crown. In just 10 days, Dreams became the largest current-grossing blockbuster in China, generating nearly 51 million USD—leading to its surreptitiously-mentioned subtitle: “The Chinese Social Network”. Alas, Sorkin had no role in the creation of Dreams; instead, Hong Kong celebrity-director Peter Chan pays just a little more than a comfortable homage to Sorkin’s Zuckerberg biopic. Dreams is loosely based around the back story of the founders of New Orient Education & Technology Group, an English-language firm that IPO’d in the US in 2006. New Orient is re-titled New Dream, and the three protagonists—Meng Xiaojun, Cheng Dongqing and Wang

Yang—are respectively played by veteran actors Deng Chao, Huang Xiaoming and Tong Dawei. Dreams then becomes a story about what young Chinese men are willing to do to achieve success and the lechery, hardship, and seduction that comes with it.

All three men meet as young, enterprising college students in the 1990s, with the same dreams as their peers: getting to America. Their college-boy antics (forcible fondles, back room hookups, nervous glances at beautiful girls, etc.) inexorably lead them toward their greater purpose of attaining a life in America. The format of the movie flits to and from scenes of a private office, where they are being accused of intellectual thievery, to the happy-go-lucky days of their youth and the stories that shaped their development into the forlorn and wise characters who sit at the glass table, a la Sorkin.

But what’s interesting, or surprising, in this movie isn’t the smarmy dialogue (Sorkin’s pointy one-liners have been converted to truth-y lectures on success and life). It isn’t even the relationships between these three up-and-coming young Chinese men that lead them to betray, support, and reject each other. What Dreams does well is to dramatize and portray the ethos of China’s youth in the 90s—an invocation of the optimism, knavery, and seduction that surround their struggle to reach America. Times Square gleams like a modern Zion and each protagonist looks longingly to the sky each time the word “America” is mentioned. Meng, leading the college book club, asks his peers to describe their generation using a single word. He offers his own view:

The most important mission of our generation is to change. Change everyone and everything around us. The only constant is our courage at this moment. If we can do it, we will change the whole world.

Wǒmen zhè yī-dài rén, zuì zhòngyào de shì gǎibiàn. Gǎibiàn shēnbiān měi gè rén, gǎibiàn shēnbiān měi jiàn shì. Wéiyī bùbiàn de jiùshì cǐ shí cǐkè de yǒngqì. Rúguǒ wǒmen néng zuò dào zhè yī-diǎn, wǒmen jiāng gǎibiàn shìjiè.

我们这一代人,最重要的是改变。改变身边每个人,改变身边每件事。唯一不变的就此时此刻的勇气。如果我们能做到这一点,我们将改变世界。

Meng believes:

There is only one place you can really change the world, America. Zhǐyǒu zài yīgè dìfāng cáinéng zhēnzhèng dì gǎibiàn shìjiè, Měiguó.

只有在一个地方才能真正地改变 世界,美国。

Wang, who claims to have the best understanding of American culture, beds Lucy (left), a journalist from the US

Dreams is the culmination of what 40-somethings in China wished they could have achieved in a simpler era: a dream of success and a better life. Every speech on success and the meaning of life delivered (and there are many of them) is a revisionist reflection on the youthful optimism of a generation, a time before cynicism and pessimism, when the metaphorical grass was greener and the pastures wider. Cheng, especially, develops his own philosophy on success. In an English class, he speaks to a group of students about his failed attempt at getting a US visa:

We have to seek victory in defeat, and find hope in despair.

Wǒmen zhǐyǒu zài shībài zhōng xúnzhǎo shènglì, zài juéwàng zhōng xúnqiú xīwàng.

我们只有在失败中寻找胜利,在绝望中寻求希望。

Cheng and his cohorts disagree with their professor’s out-dated opinions on the USA

When New Dream English School turns out to be a success, Cheng delivers more truthiness to a stadium packed with students who wish to study abroad:

What is a dream? It’s the thing that allows you to draw happiness from persistence.

Mèngxiǎng shì shénme? Mèngxiǎng jiùshì yī zhǒng ràng nǐ gǎndào jiānchí jiùshì xìngfú de dōngxi. 梦想是什么?梦想就是一种让你感到坚持就是幸福的东西。

In response to a journalist’s question on his secret to success, he explains:

When you realize failure is only a detour, you are already on the way to success. Dāng nǐ yìshí dào shībài zhǐshì wānlù, nǐ jiù Yǐjīng zǒu zàile chénggōng de zhídào shàng. 当你意识到失败只是弯路,你就已经走在了成功的直道上。

This desperate hope for a better life is, ultimately, Director Chan’s justification for a relaxed moral compass on controversial issues like copyright infringement. The film begins amidst legal proceedings, during which the three founders are accused of stealing intellectual property.

“You are thieves,” the American lawyer at the table snarls. “I memorized the entire Xinhua Dictionary, and I was considered a mediocre student,” Cheng retorts, glaring down at his American counterpart. “Chinese students are extremely adept at taking exams; you can’t imagine what they’re willing to go through to succeed.” It’s another reflection of the Chinese ethos and thought: China, the underdog, oppressed by the American bully, rife with neo-imperialist undertones, peddling a system into which each and every young Chinese strives to assimilate.

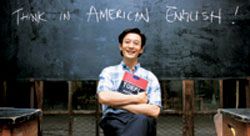

The characters first opened their English school in an abandoned factory

Meng, the only one who receives a student visa to go to the US, is cheated, beaten, and bullied by his American counterparts, who are portrayed as cold and willing to pull the rug out from under his feet. The American Dream is destroyed, not by Meng’s lack of talent, but because Americans are emotionless and unkind people who fail to take care of their pitiful guest. All of America is out to get him: customs agents search him, cab drivers curse him out; even secretaries won’t give him an appointment. “They don’t respect us,” he grits. “That’s why I’m out for myself and myself only.”

Chan’s co-opted Chinese vision of America effectively sets up the biggest straw man of the movie. It’s an aesthetic that not only victimizes young, “aspiring” Chinese entrepreneurs who aren’t afraid to backstab, cheat, lie, and steal to get what they want, but fetishizes them as national heroes. In a scene when Cheng and Wang are enjoying their newly-gained success by drinking and singing in a KTV bar, a conversation ensues:

Cheng found his true calling as an English teacher specializing in TOEFL preparation

Wang: What do you do if life deceives you? Jiǎrú shēnghuó qīpiànle nǐ, nǐ huì zěnmebàn? 假如生活欺骗了你,你会怎么办?

Cheng: You are drunk. Nǐ hē duō le. 你喝多了。

Wang: You deceive life back! Nǐ yě yào qīpiàn huí shēnghuó! 你也要欺骗回生活!

Meng, Cheng, and Wang speak to stadiums to tumultuous applause and lecture to enraptured audiences: the hubristic finger-shaking and Art of War-like speeches encapsulate the message that Chinese people are tired of being trampled upon, and that America’s comeuppance is long due. Cheng tells his two comrades during their lunch break:

Eat up. We’re going to storm America by

force.

Chī wán fàn, zánmen qù gōngxiàn Měiguó.

吃完饭,咱们去攻陷美国。

Characters fight over whether or not to take the company public

As one of Hong Kong’s most revered directors, it is surprising to see how much Peter Chan panders to this dog-eat-dog aesthetic: one that fully asserts that “China is here to stay, deal with it!” The message is, not surprisingly, very popular with Chinese audiences—particularly those who see the US as an aggressor and a barrier to China’s entry into the world market. Yu Minhong, the head of New Orient upon which the character of Cheng is based, wasn’t a part of the creative process in the writing of Dreams, nor did he even support its creation. As entertaining as one might find the notion of The Chinese Social Network, Dreams is simply just that. In some meta-twist of irony, Dreams’ defense of copyright infringement extends to its own hijacked formula—a Chinese take on a film and format that has already made its global mark. The fact that the biggest blockbuster in Chinese film is known as a lifted and repackaged product is telling in how far it has to go to meet the demands of a global audience. Ultimately, Dreams won’t do well anywhere else, for the simple reason that it’s only tailored to tell Chinese people what they’ve already been hearing for years: “Take what you can, the world is yours!”