Economics of caterpillar capitalism

Karen Chen, a normally rather placid housewife and mother of two, is getting worked up. “You wouldn’t believe it,” she tells me, as outside a gentle breeze ruffles the manicured lawns of her Beijing suburban compound. “The price has gone up so much in the last few years; it’s ridiculous. Five years ago you could buy one for 50 RMB or so. These days, it costs 200 RMB—just for one!”.

Chongcao, ounce for ounce, more valuable than gold

The object of Karen’s indignation is a semi-decomposed caterpillar with a fungus growing out of its head. It is known as yartsa gunbu in Tibetan, or dongchong xiacao in Chinese (known colloquially as chongcao). This strange creature from the Himalayas has long been important in Chinese medicine and is held to be a cure for ailments ranging from baldness to cancer. Karen believes that it could boost her daughters’ immune system, and she isn’t the only one to put her faith in its powers. China’s rapid economic growth has meant that cancer patients, speculators, and even those looking for an impressive present for their boss, now have the means to spend ever-increasing amounts on this rare creature. Over the past few years, demand for chongcao has increased to the extent that, as of 2012 it was ounce for ounce more expensive than gold.

But magical cures and astronomical prices are only half the story. While the medicinal benefits of chongcao are questionable, the effect such levels of demand have had on life in the Tibetan plateau is very real. I heard talk of a “gold rush” out west, tales of Tibetan herders coming down from the mountainsides suddenly rich.

My interest piqued, I began to read up on the subject. It soon became clear that if I wanted the whole story I needed to see it for myself. I decided to follow the chongcao trail, from the Beijing chain stores where Karen bought hers, right back to the villages where those who picked the caterpillars lived.

My first stop was Xining, capital of Qinghai Province. I’d heard China’s largest caterpillar fungus market was located here, and eventually, I tracked it down to a dusty part of town behind the long distance coach station.

Having read articles describing the market as being comparable in size to a district, I expected to find large hangar-like structures, row upon row of stalls, and Tibetan traders hauling sacks stuffed with fungus, fresh off the mountains. What I found was a small half-demolished courtyard, surrounded by almost identical concrete shops, each with four characters printed on their doors: “winter (冬 Dōng) bug (虫 Chóng) summer (夏 Xià) grass (草 Cǎo)”. The area outside was packed not with sack-wielding Tibetans, but with plastic-bag carrying Hui Muslim traders, who, it turned out, have almost exclusive control of this part of the chongcao trade.

There are many stages a chongcao goes through before it reaches the medicine shops of Beijing and other cities. The Xining market is one of the final staging posts, and as this year’s season neared its end, there were particularly large numbers of small traders from across the Tibetan Plateau bringing their chongcao to middlemen who sold them on in bulk. There was excitement in the air as kilos of little dried caterpillars changed hands and deals worth thousands of RMB were struck.

Ma Rui, a young Hui trader, was carrying a wicker tray with about 50 caterpillars when I bumped into him. Thinking about how much Karen paid for each individual caterpillar, I wondered how much this haul must have set him back. “This is nothing,” he said, indicating to what looked like two shopping bags bulging with muddy roots at his side.

A foreigner at the chongcao market was something of a novelty, and Rui decided to take me to his uncle’s shop to show his friends. I was led to an unfurnished concrete shell protected by two steel doors, behind which lay two beds, an old television set and three giant safes backed against the wall. A short while later, a nervous looking man, the original owner of the two plastic bags, appeared and it was explained to me that the two parties had negotiated outside, but had returned to the safety of the shop to complete the transaction. It soon became clear why, as Rui slowly counted out a wodge of 100 RMB banknotes about three-fourths of an inch thick.

Having left Rui’s shop, I encountered Ma Honglu. He stood overseeing his small team of Hui women, who spent hours squatting in a circle scouring the fungus with what looked like shoe brushes, turning them from the muddy roots that changed hands in Rui’s shop, into the golden worm, or “China’s treasure” as he called it. Honglu had spent the past 10 years driving around the villages in the Himalayan Mountains, trading with Tibetan chongcao diggers, and even now he still had caterpillar fungus fever.

“You want to see a live one?” he asked, recognizing a fellow enthusiast in me. Whipping out his phone he began pulling up images of what looked like the sort of maggot you’d dig up in your own garden.

“What about these; they’re over 20 centimeters long!”.

Honglu explained what made some caterpillar fungi more valuable than others: the best ones have long bodies and small heads. A larger fungus on the caterpillar’s head indicates

fewer nutrients in the caterpillar and diminished medicinal potency.

The process by which a caterpillar fungus is created begins during the Himalayan Autumn, when a fungus attacks the ghost moth larva as it lies buried in the topsoil. As the Himalayan winter sets in overhead, the fungus kills then mummifies its caterpillar host, sucking out nutrients from the caterpillar’s body to grow stalk-like from the top of the caterpillar’s head. By late spring, after the snow melts, the small stalk-like fungus can be seen protruding from the grass.

Caterpillars from different regions also differ in value. I had read that the highest quality caterpillars are to be found in Yushu (玉树), a Tibetan area lying to the north of the Tibetan Autonomous Region, and the traders I spoke to in Xining confirmed this. Unfortunately for me, Yushu is not exactly close to Xining. It is, at present, a mandatory 22-hour bus ride away. The mandatory part, I discovered, is an attempt to reduce the number of accidents occurring along this stretch of road. Unperturbed, I decided to put my life in the hands of the Sanjiang Bus Company and boarded the 12:30 sleeper bus to Yushu.

Seventeen hours later I awoke to find myself in a kind of moonscape with not a living thing in site. Outside, my driver and one of his cronies seemed to be attacking a door to the undercarriage of the bus with a pickaxe. Thud, thud, thud. My head throbbed.

A Hui caterpillar fungus trader closes a deal over the phone

I turned to one of my fellow passengers and whimpered “tóuténg(头疼)”—“my head hurts”. “Hahaha,” he replied to me with a distinct lack of compassion, “you’re just having a reaction to the altitude.” “You’re not used to it,” he added proudly.

I spent the remaining five hours of the journey either trying to access the 3G on my phone to find out whether the altitude sickness I was experiencing would kill me, or with my eyes closed pretending I didn’t exist. Fortunately Yushu is at a lower altitude than parts of the route, and as we neared our destination, I miraculously felt better.

While Yushu is famous for its caterpillar fungus, it is also etched in many Chinese minds for an altogether more unfortunate reason. In 2010, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake devastated the town, destroying 85 percent of the buildings, and leaving nearly 2,700 dead.

Having previously visited Yushu in 2008, I expected to find the town changed, but I was unprepared for the extent of the upheaval. It seemed that even three years after the earthquake had struck, at least 70 percent of the town was still under construction. All over town, hordes of Sichuan construction workers toiled in the scant oxygen to build a newer, bigger Yushu.

Hui women sitting to clean chongcao

My first thought was to find somewhere to stay. Not easy when local hotel owners decide to rebuild their signs long before the rest of the hotel. Eventually I found a room, which for 240 RMB per night offered electricity and water between 7:30 and 11pm. I later discovered that this was produced by a generator just outside the hotel, which caused my entire room to vibrate whenever it was switched on.

At this time of year, everything in Yushu revolves around the caterpillar fungus trade. Its restaurants throng with visitors from nearby villages coming to sell their findings. Along the road outside the museum, young Tibetan boys dressed in the latest fashions, and older Tibetan men in traditional robes stand haggling with middlemen.

The presence of hundreds of villagers, instantly rich after selling their caterpillars, also has the effect of supercharging the local economy. Further down the street, I found business booming in Yushu’s market, as herders with thousands of RMB in their pockets splurged on ornamental belts, fashionable coats and iPhones from the town’s very own fake Apple store.

Outside the museum I came across Shuice Xuezu, who had traveled 120 kilometers from his village to sell his caterpillars. Resplendent in his robes, his dark face partially covered by his cowboy hat, he explained in simple Mandarin that he had about 300 caterpillars to sell and had been looking for a bidder all morning. From asking around, I’d gathered that the going rate was around 50-60 RMB per fungus, no small sum considering that, in 2010, the average annual income of Yushu county’s rural residents was just 3,663 RMB. Shuice was asking for 100 per caterpillar, a high price, but he maintained his bugs were of the best quality. Aware that the presence of foreigners was hampering his chances, I left him to it.

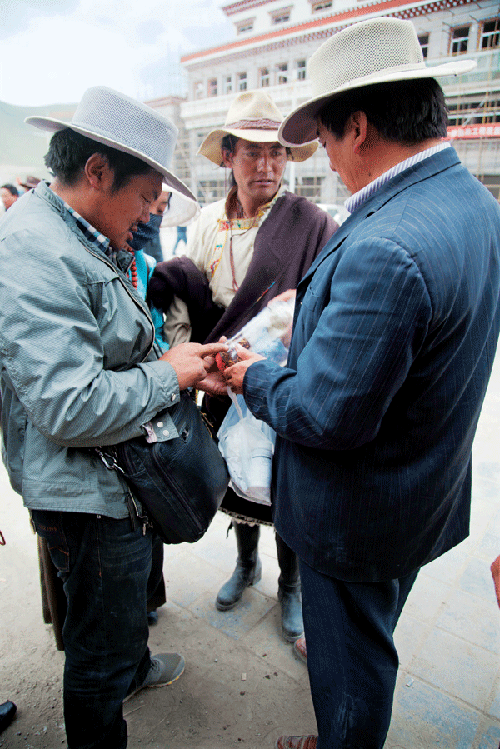

A trader hoping to purchase chongcao from the local villagers

Later, in the smoky Snow Mountain Tibetan Restaurant I met Zhaxi Dongdrup, a Yushu native, and one of a minority of Tibetans to have been to university. Of all the people I’d met during my trip, Zhaxi appeared to be the only one who seemed jaded by the changes chongcao had brought to his hometown.

“It has changed life completely. When I was a child, no one cared about the chongcao; the people who did bother to collect them would come into town carrying whole sacks. You could buy one for just 5 fen.” Zhaxi explained that while the caterpillar fungus is also recognized as having medicinal uses in Tibetan medicine, it is merely a complementary element. It has limited healing properties when taken alone and therefore limited value.

“Around 10 to 15 years ago people started to realize you could make money from the caterpillars and began going out to dig for them. Every year since, the money you get for chongcao has gone up. These days, what you make from one month’s digging is easily enough to last you for the whole year.”

At about this point, a group of young Tibetans in high spirits came charging into the restaurant. All were dressed in variations of a fur-collared blazer, tank top and giant amber necklace combination, which seemed to be the latest in Tibetan fashion. They ordered fruit beers and sat at the adjacent table, staring in our direction in unashamed curiosity, the whites of their eyes shining from their wild, weather-beaten faces. Eventually, two of them picked up the courage and came over to our table. It soon became apparent that they didn’t understand Mandarin, but with the help of Zhaxi, we manage to strike up a conversation.

Merchants hock and trade the highly sought after chongcao

I learned that Gele Nobu and Uchi Dulda had just come from Zá duō(杂多), one of the regions where the harvest was best this year. Despite their modern get up, these boys still lived the same lives their ancestors had followed for generations before them, taking the family yaks up to the mountain pastures in the summer and spending the cold months in the family’s winter house. The money they made from chongcao was essentially the only income they made all year.

And this year had been especially good. In just over one month Uchi Dulda, with the help of his brothers, had managed to pick 2,000 chongcao, while Gele Nobu claimed to have single-handedly picked 1,000. A quick calculation told me the boys must have earned about 120,000 and 60,000 RMB respectively. An absolute killing, if they’re to be believed. They were now spending a couple of days having fun in what was, for them, the big city, before returning to their families.

Zhaxi unexpectedly sighed, “You know people like them drive up the prices. A T-shirt you could get for 40 RMB in Beijing will cost you 100 RMB here. It’s the same for everything. They have no idea what the value of things is.” I thought about my vibrating 240 RMB a night hotel room and realized Zhaxi had a point.

There was one thing I didn’t understand about the caterpillar trade. If these bugs were so lucrative, why didn’t people from other parts of China come to dig for them too? “It’s not allowed,” Zhaxi explained. “Only locals in a particular area can dig for the chongcao. If an outsider wants to dig they have to buy a permit from the local government. And they are really expensive.”

Yushu still wears the marks of the earthquake earlier 2010, with reconstruction night and day

According to the local authorities, the permit system has two functions: to prevent over-harvesting and to stop territorial disputes between groups of pickers. A further consequence of the system is that it has allowed the local Tibetan population to retain a virtual monopoly on harvesting chongcao. This final fact has had a profound effect on today’s Yushu. I began to notice that the majority of the businesses in this Tibetan town were, well, not Tibetan. Even the chef serving Tibetan food in the Snow Mountain Restaurant was a cheery Han Chinese from neighboring Gansu Province.

No matter who I asked, I was told that Tibetans simply weren’t interested in doing business. They didn’t need to; they had the chongcao. As a result, a curious situation had arisen in the town where almost all economic activity consisted of Tibetan demand being met by Han and Hui supply.

Having been in Yushu for several days, I wanted to see what impact the chongcao were having on the surrounding villages. I met Chenglin Jianglong, every inch the fashionable young Tibetan, lounging in front of his minivan, his Apple baseball cap matching his iPhone. Inside, his van was decorated with cartoon characters and pictures of the Dalai Lama, all paid for thanks to the chongcao. As Chenglin revved up the engine and switched on the CD player, we pulled out of Yushu to the sound of Buddhist chanting played at full blast and sped off into the mountains.

Tools for finding chongcao are delicate. For the Tibetans in the area, it could be their most lucrative job all year. Image courtesy of Timothy O’Rourke

An hour later we arrived in Chenglin’s village. As I climbed out of the van the first thing that hit me was the silence, a change from the banging and drilling of Yushu. Chenglin’s village was a remote, dusty place lying between two steep hill faces, with a river and a road running just below, connecting it to the rest of the world. Chenglin’s village was part of a recent trend across the Tibetan plateau of voluntary and encouraged settlement of previously nomadic families. It is in places like this where reliance on the caterpillar fungus is strongest. Here, where the harsh climate and remote location rule out large-scale agriculture and business, villagers have switched their allegiance from yak herding to caterpillar fungus digging for survival.

So far it has paid off. Many houses had satellite dishes and motorbikes parked in front of them, and some—like the iPhone-toting Chenglin—even had cars and minivans. In fact, almost all who were involved in the caterpillar fungus trade would have found themselves richer, and I couldn’t help feeling that this seemingly guaranteed income must have been a large incentive for Tibetans to sell their yaks and opt for a sedentary life in places like Yushu and its surrounding villages.

However, an economy reliant on one source for income is always vulnerable to collapse. In recent years, environmentalists have warned that even with restrictions placed on digging for chongcao the caterpillars are in danger of being harvested to extinction. A study published in early 2013 by scientists from the University of Massachusetts predicted that, because of over-collection and environmental changes, the chongcao may no longer be available in as soon as 10 years’ time.

I thought about what might become of villages like Chenglin’s should the chongcao die out, and prayed that the environmentalists would be proven wrong.