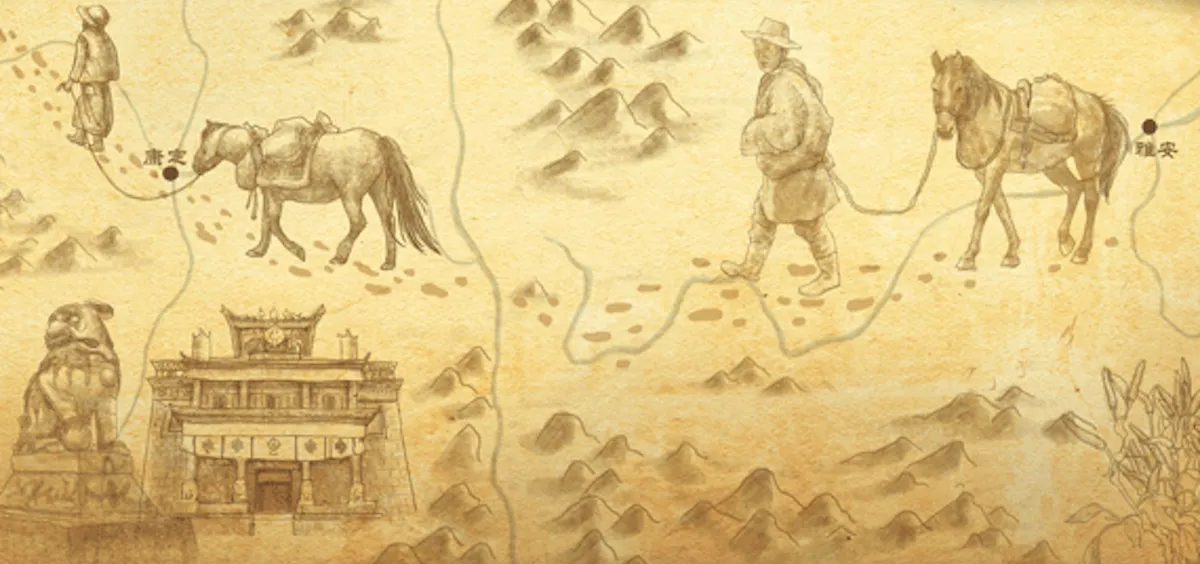

For centuries, the rugged landscapes of western Sichuan played host to caravans of the legendary Tea Horse Road

From a rocky ledge above western Sichuan’s mighty Dadu River (大渡河), my brother and I watch, transfixed, as Jamyang and his family go about their business. Hunched double under massive loads of dried chili pepper, the procession of men and women walk steadily across a swaying suspension bridge of wire and decayed wooden boards. As the wide mountain torrent churns past thirty feet below, the noise is deafening.

Jamyang and many other local villagers will brave the Dadu several more times today as they transport their fiery harvest across its frothing waters. Despite the toil and obvious danger, to them, it’s all in a day’s work. “We got a fair price from the local merchant,” Jamyang tells me happily, before drawing vigorously on a well-worn pipe. “Maybe there’ll even be some spare money to fix up the bridge,” he adds mischievously, before setting off for another sack.

Highly-prized Sichuan tea was once exchanged for Tibetan thoroughbreds

In a landscape that can be as unforgiving as it is dramatic, the people of Jamyang’s remote community are seemingly accustomed to taking risks. Row upon row of quaint, red-and-white stone houses sit at the base of a gigantic, overhanging rock face, tempting gravity or seismic forces to do their worst. Still, as I’m quickly discovering, this is a land that favours fortitude and a certain insouciance in the face of danger.

Stretching north to Gansu, south to Yunnan and west to Tibet, Sichuan’s western highlands sit at the easternmost fringe of the vast Tibetan Plateau. Rearing up from the tableland around Chengdu, capital of Sichuan, this region boasts some of Asia’s most thrilling scenery—remote valleys dotted with shaggy yak and delicate alpine blooms, golden-roofed temples and whitewashed stupas, and soaring, snow-clad peaks.

Jamyang’s daughter Kunsang comes over with two glasses of green tea. The delicate twentysomething has been carrying bags of chili that equal her own body weight for the last hour, but still manages to look unflustered. An ornate hair braid frames her prematurely aged yet attractive face.

“We often sing of the beauty of our surroundings,” she explains, as we sip the scalding brew. “Some people say this land is like a fortress paradise. It’s hard to get here, but once you arrive, you won’t want to leave.” If James Hilton’s Shangri-La does exist, it could well be tucked away in this wondrously wild corner of south-west China.

My brother and I are exploring western Sichuan because of a road. A road that wasn’t paved, that no longer exists, and that was actually a network of rough mountain trails. This was the chamagudao, or “Ancient Tea Horse Road” (茶马古道 Chá mǎ gǔdào), a central trade route for the exchange of Tibetan horses and Sichuan tea. As it developed, the chamagudao came to play a crucial role in communication and cultural exchange between present-day Yunnan, Sichuan and Tibet.

While the chili peppers of Jamyang’s village are now widely cultivated in western Sichuan, another crop of a more soothing nature has had a far greater regional influence. The mountain ranges here boast some of the richest green tea-producing slopes in the world.

“After Sichuan tea was first introduced into Tibet over a thousand years ago, it quickly became a key part of the diet there,” explains our Chengdu-based historian and western Sichuan tour guide Li Qiang after we return to his trusty Chinese minivan to continue our road trip.

A villager carries a sack of chili peppers across the Dadu River

“Many Tibetans are big meat-eaters and it helped in their digestion—the leaves were chewed and also used to make po cha or yak butter tea,” continues Li. “Right up to the early 20th century, tea caravans crossed between western Sichuan and Tibet. Bags of leaves were traded for high-quality Tibetan horses bound for the emperor’s cavalry.”

On the fertile flanks of Mount Mengding (蒙顶山), just outside the town of Ya’an (雅安), tea bushes still cover the ground like a gently rippled green blanket. “Mengding tea is renowned in China,” says local farmer Wang Lei after we pull over beside his small house. The porch is decorated with rows of drying corn cobs and tobacco leaves. “In the past, teams of porters would take away bricks of tea from plantations around here. Both tea and silk were transported into Tibet and beyond to India and Europe.”

Although the chamagudao has long been rendered obsolete by modern highway construction, the centuries of cultural exchange and regional commerce it promoted are still evident across much of western Sichuan, and a growing number of adventurous tourists are now choosing to explore its legacy.

After a quick tour of Wang Lei’s plantation we bid him farewell. In the rear view mirror I watch him begin to throw drying chili peppers onto the ground in front of his house like confetti. We’re bound for Kangding (康定), one of the Tea Horse Road’s major rest stops and now the destination for most of Wang Lei’s produce.

Shoehorned into a steep valley and bisected by the white waters of the Zheduo River (折多河), today Kangding is a fascinating mix of Han and Tibetan cultures. The days of leaf-laden caravans may have long gone, but the town still has the air of a remote trading outpost, with streetside markets peddling yak meat, giant wheels of yak butter and bricks of tea from around Ya’an.

A Khampa Tibetan leads his trusty steed through the streets

Kangding is famous throughout China for its spectacular panoramas. Overlooking the town and accessed by cable car, the summit of Mount Paoma (跑马山) offers awe-inspiring views toward the 7,556-meter Mount Gongga (贡嘎山), an elegant pyramid of granite, snow and ice once thought higher than Everest. In the 1930s Mount Paoma’s beauty was described by Sichuan musician Li Yiruo in his catchy “Kangding Love Song” (《康定情歌》Kāngdìng qínggē), still one of China’s most popular folk ballads. “Chamagudao porters would carry heavy packs of tea the 180 kilometers from Ya’an all the way to Kangding, via Tianquan and the treacherous Mount Erlang (二郎山),” explains Ian Ford, an Englishman who also runs tours of western Sichuan. “Here the tea was packed again and put on the back of horses to continue the journey on to Lhasa and other Tibetan areas.

“Due to dangerous terrain on the Ya’an side of the route, horses were not able to transport heavy loads here,” continues Ford. “That’s why the work was done by porters. It involved backbreaking effort, as overloaded men moved along twisting mountain paths, much of the way at dangerously high altitudes in sub-zero temperatures.” Dropped off on Kangding’s main street by Li Qiang, my brother and I indulge in a spot of people watching. Circumambulating the centrally located Anjue Temple (安觉寺), hand-held prayer wheels spinning wildly, Kangding’s Tibetan population adds a bright splash of color to the neighborhood. These are Khampa Tibetans, renowned as much for their fighting skills as religious piety. Nowadays, however, the silver daggers are merely decorative—the biggest battle is all about the longest hair braids and most elaborate headgear.

Drying tobacco leaves on the slopes of Mount Mengding

Kangding’s cosmopolitan demography is also reflected in its cuisine. Tsampa (a kind of dough made with roasted barley), barley beer, yogurt and buns filled with yak meat are all local favorites, as is the ubiquitous yak butter tea. Tenzin, a nearby stallholder, inveigles my brother into trying a complimentary mugful.

At first sip my brother’s grimace indicates that Tenzin’s concoction has fallen far short of his expectations. Having already warned him about po cha’s acquired taste, I watch with spiteful glee as he struggles to finish off the rancid brew. Tenzin beams and offers a refill. My brother mimes a full stomach and smiles weakly.

“Foreigners generally don’t like the taste of it,” says Tenzin, “but Khampa Tibetans love it. I take the tea leaves and soak them in hot water for a few hours. Then I add a chunk of butter, a few spoonfuls of salt, and a cup of milk, and mix everything together. You’d appreciate it even more if you were a couple of thousand meters higher up and it was 30 degrees colder.” I don’t bother translating the recipe for my brother.

Color and culture at Anjue Temple in Kangding

One place close to Kangding that may just be perfect for yak butter tea appreciation is Mount Gongga. After a night in Kangding we’re up at dawn to continue our journey past this sacred Khampa peak, soaring high above western Sichuan’s jagged topography.

Mount Gongga’s splendor belies its treacherous nature. Until 1999, more people had died climbing it than conquered its summit. These days, most visitors opt for a cable car ride up to a 3,600-meter platform beside Hailuogou Glacier (海螺沟), one of four frozen rivers that creep down the mountain’s plunging flanks.

“On a clear day you can see Minya Konka all the way to Chengdu,” explains Tang Lei, a high-altitude vendor hawking boiled water and fried dough balls next to the cable car terminal. Above his stall hundreds of radial prayer flags rise and fall hypnotically in the breeze, while pungent incense smoke drifts from twin stupas beneath. Despite its cloudy veil, the spirituality of western Sichuan’s supreme peak remains as palpable as ever.

Prayer flags flutter in the breeze above Tagong

Beyond Mount Gongga, the road twists and turns as it fights the gradient. An endless succession of switchbacks offers ever more stunning views over pine forests and the craggy mountain range. Giant boulders stained with bright ferrous deposits lie discarded beside melt-water streams, while overhead gossamer strands of lichen decorate branches in a primeval spider’s web of vegetation. It’s a magical place to be on the road.

Western Sichuan is not all mountain, forest and river. Three hours out from Kangding and Li Qiang’s expert driving skills bring us to the town of Tagong (塔公镇), from where a high altitude sea of grass stretches toward the horizon. Ringed by a necklace of snowy peaks and studded with monasteries, temples and Khampa villages, this lush tapestry of undulating meadows and hills is a pristine environment where warrior horsemen once honed their fighting skills.

“People usually end up staying in Tagong longer than they plan,” says Sally Norbu, Khampa co-owner of the perennially popular Sally’s Kham Restaurant. “We have a very vibrant and special community here.” Stretching from hillside to hillside, a long line of huge prayer flags dips and sways overhead, while an endless procession of old women in traditional dress circle Tagong Temple’s faded red walls. It’s hard to disagree with her sentiments.

The sprawling grasslands of western Sichuan have long been associated with horses, both as beasts of burden and battle, and as commodities for bargaining. The tea caravans and Khampa warriors have long since disappeared, but the horse remains one of the best ways to get around, both for locals and visitors.

A muddy river rushes through the beautiful scenery of Kangding in western Sichuan

“For Khampa men, riding horses has always been a glorious thing,” explains Sally. “On horseback they feel proud to be the descendants of the legendary Tibetan King Gesar, about whom an epic poem is written. As they gallop across the grassland with the wind in their face, yelling at the top of their lungs, Khampas have a great sense of togetherness and honor.”

“In Tagong we have a popular song,” she continues. “It says: A good steed is like a swift bird, a golden saddle is like its feathers. When the bird and its feathers are together, then the highlands are easily crossed. Khampas don’t make so many great journeys as before, but there are plenty of horse festivals around here where the local men can prove their strength and ability.”

The Tagong grasslands remain the perfect place for a spot of horse riding. An hour later and my brother and I are each seated on somewhat diminutive Khampa ponies. On the outskirts of town, behind our local guide, we ride past the spectacular Muya Pagoda, its massive golden roof and central stupa glittering in strong sunshine.

Beyond Muya, fields of pink prayer flags attached to wooden stakes flutter in the breeze as the crosscountry trail wends its way through a carpet of grass and vivid blue flowers. Semi-wild horses roam free here, their bellies fat from grazing, while restless herds of yak search out the lushest pasture. Vultures soar effortlessly above, casting moving shadows over the picturesque landscape.

With flasks of green tea tucked behind each saddle, the day’s outing seems the perfect culmination of our chamagudao adventure. Tea and horses still play a vital role in many people’s lives here, and the region’s enduring remoteness still adds to its appeal. The terrain may be inhospitable, but the warmth of the welcome is deep and sincere. A Sichuan Shangri-La indeed.