Cherry Lips, Ruddy Cheeks, Erotic Avatars – the women who made us stop to look

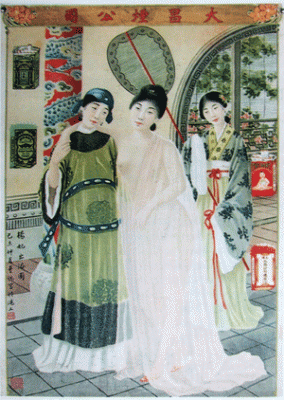

When China’s first pinup model began spreading like wildfire across the country in 1914, she’d already been dead for 1200 years. But this did little to dampen the popularity of her likability, which was plastered across ad posters commissioned by the Great China-France Drug Store. (After all, as any good adman knows, the connection between desire and reality is often—and often necessarily—tenuous at best.)

Yang Guifei

Like so many iconic images of women, this one was a mix of tradition, sex appeal and a little bit of voyeurism (think Marilyn Monroe with her skirt blowing up). The painting, which had been rendered by an ad artist by the name of Zheng Mantuo (郑曼陀), depicted an ivory-skinned girl stepping out of a hot spring. From the neck up, she was as conventionally pretty as they come—cherry lips, an egg-shaped face, long hair piled into a bun, but from the neck down, she was a thrilling scandal, dressed only in a silk robe that revealed her body in the seductive style of a Western nude.

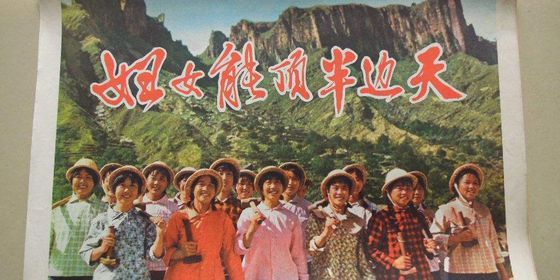

Painters were still years away from exhibiting nudes in public, but Zheng’s calendar was distributed widely to his employer’s customers and business associates. The image took on a life of its own, and soon Zheng had more work than he could handle. Meanwhile, the woman in the painting faded into the ether, only to spawn generations of nameless, but equally iconic, daughters: the smirking glamour girls of 1930s Shanghai; the ruddy-cheeked comrades pedaling revolution in the 60s; the doe-eyed sprites that today sell everything from cosmetics to cell phones. Like Zheng’s girl, they exist in our collective consciousness as images, as fantasies, as the silent objects of our gaze. And in the process, these women have become public property of sorts, wiped clean of personal histories, voices, names, and desires.

Yet, these were real, flesh-and-blood women, with stories worth remembering, so here’s a short history of the poster girls of China, starting with the woman in the hot spring. Her name was Yang Guifei.

Yang Guifei (杨贵妃, 719-756)

Life of Decadence

The posters may have scandalized traditionalists in 1915, but Yang Guifei (719–756) probably wouldn’t have batted an eyelash. Yang was a Tang Dynasty (618-907) imperial consort considered one of China’s “four classical beauties (四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ),” who performed at court as the Xuanzong Emperor’s favored singer and dancer.

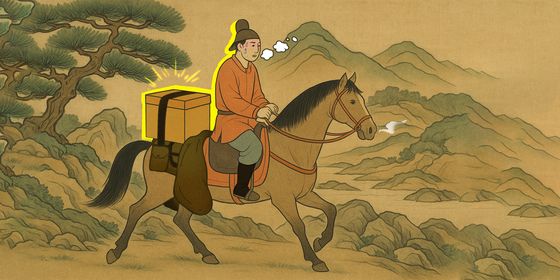

In her heyday, she indulged in an ostentatious lifestyle that would have made Marie Antoinette blush. A staff of 700 silk weavers and embroiderers toiled tirelessly over her garments, and her appetite for fresh litchis was legendary. To ensure that the fruits’ flavor and color met her standards, a system of rapid horses was set up along the hundreds of miles of road that separated the best litchi farms from the imperial capital of Chang’an. Horses and officials were driven to exhaustion to satisfy the consort’s cravings.

Eventually, popular resentment mounted against the decadent imperial court, and a series of natural disasters in the winter of 755 prompted an armed insurrection. Yang fled in the direction of Sichuanalong with the emperor and his coterie of close advisors. On the way, the troops mutinied, killed Yang’s cousin and demanded that Yang be executed as well. To save his own life, the humiliated Xuanzong Emperor gave permission for Yang to be strangled. Rather than wait for the inevitable, Yang—then barely 40 years old—hung herself on a silken cord given to her by Buddhist monks. She was given the title of Empress two years after her death and has been celebrated by generations of Chinese artists. But it wasn’t until 12 centuries after mob rage drove her to suicide that the public would embrace her again as a sex symbol—and the face of the China-France drugstores.

Butterfly Wu (胡蝶, 1907-1989)

Shrieking Refinement

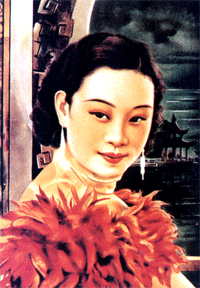

Butterfly Wu

Classical beauties would not hold the public’s attention for long. By the 1930s, 1200-year-old women were making room for modern stars like Butterfly Wu, a wildly popular film actress from Shanghai. With her sleek glamour and coy, dimpled smile, Wu was the epitome of China’s modern woman: fearless, sophisticated, cosmopolitan. Dressed in the silk qipao typical of Shanghai ladies of taste, Wu and other “beautiful girls” (美女 Měinǚ) of the twenties and thirties lent their images to ads for cigarettes, beauty products, and other emblems of refinement.

“They were selling this idea of a new, modern woman who was going to help transform the country,” says author Lisa See, whose novel Shanghai Girls follows two fictional models of the day. “A lot of what they were doing was completely unheard of even 10 years before: wearing a bathing suit, climbing out of a pool, driving a car with the top down, shooting a bow and arrow, drinking champagne in clubs, dancing in clubs”—snapshots of modern living making their first foray into Chinese popular culture.

The models were bohemian friends of artists, notorious call girls, and actresses. In the last category, Butterfly Wu was undoubtedly the most famous. Known in Mandarin as Hu Die, Wu was the star of the first Chinese talkie, “Singsong Girl Red Peony (《歌女红牡丹》Gēnǚ Gōng Mǔdān, 1931)”, in which she played a famous singer who squanders her money on a no-good husband. Wu’s every move was chronicled by the “mosquito press” of the day, and news of her exploits reached even the far shores of America. Reviewing “Singsong Girl Red Peony” in 1931, the Associated Press noted that “her vocalizing has a quality all its own which makes it sound like a prolonged shriek to Western ears, but she possesses, by Chinese standards, one of the best voices in the country.”

On the occasion of her wedding in January 1936 to a wealthy Western wine merchant, Henry Luce’s Time magazine heaped on similarly backhanded praise of the “Chinese Cinema Queen.” The ceremony at Trinity Cathedral, Shanghai, was captured for Chinese newsreels, a decision that had scandalized the Time editors. “The hubbub of Chinese in the Cathedral was so loud,” they wrote, “that the Dean had to shout the Anglican service at the top of his voice to get it on cinema soundtracks distinctly.”

Butterfly Wu is revered today as one of the great actresses of early Chinese cinema. Her career continued into more turbulent times, and she starred in left-wing political films. The press falsely reported her death during a raid of Hong Kong in 1942, but in fact she escaped the city as a beggar with her family that year, continuing to act until the 1960s and dying peacefully in Vancouver in 1989.

Liu Hulan (刘胡兰, 1932-1947)

Anonymous and exemplary

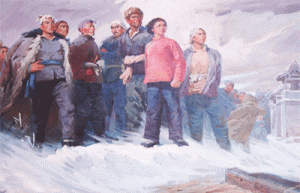

With her short, blunt hair, stern eyes and sturdy form, Liu Hulan was about as far from Butterfly Wu as a poster girl could get. In paintings she stands with her fists clenched, mouth set in a line of determined defiance. Though no one knows what she really looked like, the eternally adolescent Liu has become an icon of Communist ideals and heroism—after dying for the revolution at the age of 14.

After the People’s Republic was founded in 1949, Liu and her ilk became the new face of the ideal Chinese woman. With revolution in the air, poster girls ceased to sell cigarettes and perfume and began to sell revolution. No longer famous stars, they were mostly anonymous working women, meant to represent socialist values, and we know very little about their lives.

Liu Hulan

The dainty Shanghai ladies of the Thirties were out, and strong, healthy working women were in. “They weigh more, they have ruddy cheeks,” says Lisa See. “Their hair, instead of being beautifully styled, is kind of cropped, or in braids.”

Although they lacked what we think of as the feminine touch, the political pinup girls of New China like Liu were worshipped as icons of style by the generation that came of age after 1949. “I wanted to be the girl in the poster when I was growing up,” writes Anchee Min, the author of many books, including the Cultural Revolution memoir Red Azaleas. “Everyday I dressed up like that girl in a white cotton shirt with a red scarf around my neck, and I braided my hair the same way.”

There was likely no greater revolutionary icon for young girls than Liu Hulan, whose story, whatever its real-life particulars, has entered CCP lore. Born into a peasant family in Shanxi, she began acting as a courier for Communist guerrilla groups at the age of 10. When she was 13, she was appointed a secretary in charge of her village’s branch of the Women’s Anti-Japanese and National Salvation Federation. Meanwhile, the Civil War between the Communists and the Kuomintang was heating up. Believing that her youth would shield her from persecution, she remained in her village as it was invaded by KMT forces. She refused to cooperate with the KMT, and paid for the decision with her life. Mao Zedong made sure her “great life and honorable death” were not forgotten.

Teresa Teng (邓丽君, 1953-1995)

A weapon of culture

Teresa Teng was at the peak of her career in 1984 when she performed in Taipei dressed in a white-sequined dress and oversized “diamond” earrings. She was celebrating the 15th year of her career, but she had only just begun to gain fame in the mainland. Cheap cassette players had flooded the market with her music despite the government’s best efforts to ban it. Pop music posters weren’t far behind.

Far away on the island of Quemoy, a Nationalist propaganda speaker broadcasted her songs toward the mainland in between anti-Communist slogans. Teng was one of Taipei’s best weapons in the culture wars: she was popular on the mainland then, and remains so today. If a Westerner can belt out just one karaoke tune in Chinese, it’s probably her hit song “The Moon Is a Reflection of My Heart “ (《月亮代表我的心》Yuèliàng Dàibiǎo Wǒ de Xīn).”

Teresa Tang

CCP officials at the time criticized Teng, saying that her albums made people “indulge in the intimate emotional world of men and women, and in a world of narcissism… Artistically, they only contribute to the shaping of listeners’ vulgar interests and low tastes.” After the trauma of the Cultural Revolution, people wanted to retreat into exactly this kind of sappy emotional dreamscape.

Teng’s looks, too, were perfect for Chinese ads of the eighties: she was sweet and alluring, without being too sexually suggestive. “The way you think a Chinese girl should look like, that’s the way Teresa looks,” said her brother at the time. With the same last name as Deng Xiaoping, Teresa became known as “little Deng (小邓 Xiǎo Dèng),” and in some ways they were similar: the slow acceptance of her songs signaled cultural reform at the grassroots, while big Deng carried out economic reform at the highest levels.

Teresa Teng died of an acute respiratory attack in Thailandin 1995. Her New York Times obituary noted that “for much of the 1980s she was a litmus test of the political winds: when the authorities eased controls, her music sold briskly in stalls in the tiniest towns; when the hard-liners clamped down, her music was banned.”

Chen Man (陈曼, 1980-present)

The poster child steps in

In today’s urban China, it’s difficult to imagine a time when a simple love song could have aroused the ire of top officials. Women’s images are everywhere, and most are bland and forgettable, but the new economy has also produced its share of virtuosos whose work may one day prove to be as timeless and definitive as those perfumed Shanghai ladies in their qipao dresses.

Chen Man

Chen Man isn’t a poster artist per se, but it’s no coincidence that Time Out Beijing recently called the 31-year-old photographer the “poster child for aspirational China and the new consumerist East.” Her images of women—sometimes conceived for commercial clients like Adidas, Nike and L’Oréal, sometimes created as fine art—beg to be tacked up in a prominent spot. Like every teenage bedroom poster, they represent an ideal to aspire to or a conquest to be gained, depending on who’s doing the looking.

At a recent exhibit at Beijing’s Today Art Museum (今日美术馆 Jīnrì Měishù Guǎn), a series called “The Five Elements” echoed the influences of the last century of poster art. Unaltered photos of working women are juxtaposed with hyper-manipulated images of their ideal, eroticized avatars. For example, a smiling carpenter hangs across from a radiant wood nymph. Fantasies of luxury sit alongside odes to labor, while a faint, dark undercurrent suggests uncertainty about where such tensions may lead.

If there’s a tension between fine art and commercial art in today’s China, Chen doesn’t see it. “The way art is in China today, every artist is a commercial artist,” she says. “You see some other artists who copy themselves and reproduce what they’ve already done to create more value, so it’s really hard to draw a line between art and fashion, or commercial stuff.”

Fine art and poster art parted ways with those early ads 100 years ago, but Chen is helping bring them back together. In the process, she’s showing that women in China can step in and take control of their own images—a new idea whose time has finally come.