An intrepid tale of carnal desire let loose in the wilds of Sichuan

There’s a saying in Chinese that goes something like this: “男不入川,女不入藏” (Nán bù rùchuān, nǚ bù rù cáng), which roughly translates as, “Men shouldn’t go to Sichuan [because Sichuanese women are so beautiful], and women shouldn’t go to Tibet [because Tibetan men are so handsome].” Like the call of the mythical sirens, the beauties of Sichuan and the studs of Tibet can steal the hearts of any hapless traveler foolish enough to cross their path.

Well, there’s no better advert for the place, I thought, and without further ado packed my bags and set off to Ganzi Prefecture (甘孜州 Gānzī Zhōu), an autonomous Tibetan region in western Sichuan, where the Khampa breed of Tibetan male (康巴汉子Kāngba hànzi) can be hunted without the need for a special permit.

First stop: the river town of Kangding (Dartsedo). Formerly known as the gateway to Tibet, the town once had a bit of a Wild West reputation, but is now a tame modern city that rests five hours from Chengdu and 2,500 meters above sea level. While it may have lost some of the hinterland allure promised in the guide book, it does offer a tempting taste of the Tibetan flavor to come. Along the edges of Kangding glow the pale colors of Buddhist sculptures, carved into the cliffs that tower protectively over the city. Through the middle of Kangding flows the powerful Dartsedo River (康定河 Kāngdìng Hé), a furious beast that bears on its back the freshness of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau above. But the attractions go beyond the natural—every night local Tibetans, mostly in modern dress, dance in a giant circle to folk ditties pumped out from streetlight-mounted speakers. Anyone can join in. I scoured the crowds, but there was no sight of a dashing Khampa hanzi.

Food offered an alternative pleasure of the flesh, and I was easily seduced by Kangding’s impressive array of genuine Tibetan fare. Even traditional Tibetan eateries of the simple working-class variety are richly decorated: patrons sit on ornate wooden benches made softer for the travel-weary rear by folded carpets, and eat bent low over low wooden tables. A couple of tasty establishments near the south end of town offered fresh yak yoghurt, sweet milk tea and steamed buns stuffed with yak meat or potatoes, the perfect breakfast to take the edge off a raging libido.

While pleasant enough, Kangding turned out to be but a little dull, its greatest claims to fame being a ballad written by a love-struck tourist in 1936, and a picturesque hill to the north. So after a few days acclimatizing, I jumped on an early morning bus bound for the real Tibet. All buses heading west leave at the crack of dawn (between 6 and 7 am), as travel is slow and torturous—vehicles not only have to negotiate hairpin bends on sheer mountain drops, but the roads beyond are little more than mud tracks (if you’re lucky) that are regularly hit by elephant-sized rockfalls.

The first stop for most people is Tagong (塔公), which lies just across the Zheduo Pass (折多山, 4,298 m). The pass marks a kind of gateway on the other side of which, the literature promised, is the real Tibet. My eyes glistened with visions of roaming Khampa hanzi, the dashing Tibetan menfolk of the Kham region, known for their horsemanship, courage and strident tempers.

It’s said that only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun, and, determined not to let my side down in the battle of the sexes, I stumbled around Tagong under the beating heat of the noontime rays. As promised, there were more mad dogs and snarling curs than you could shake a yak bone at, but not a whiff of any Khampa hanzi. No doubt they were all indoors, sleeping off the previous night’s excesses.

On the edge of the town was the main monastery, whose golden eaves glittered naughtily in the sun.

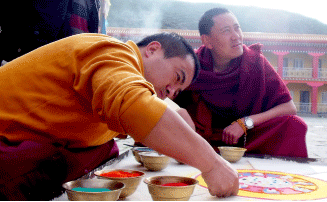

The main temple provided welcome shelter from the sun, which shines oven-hot at 3,700 meters, but was not quite the peaceful haven I had anticipated. “Come over here and join us,” one 30-something monk with a wicked grin yelled over at me. He was dancing to some techno bleating from a small tape deck, his maroon robes whirling, arms waving in the air. His chubbier monk friends giggled from their perches on a bench. I watched him dance, and shook my head, laughing, until he was exhausted. At the back of the temple, shielded on all four sides by a curtain, was a magnificent sand painting. These mandala (曼陀罗, a symbol of spiritual and ritual significance in Buddhism), as they are called, are painstakingly made by a team of monks funneling sand onto a penciled sketch. They were delicate, gloriously colorful and symmetrical across more dimensions than I could count. In a few days at a special ceremony, the mandala would be destroyed, an act meant to symbolize the transitory nature of life. The monk swept his arm above the mandala and grinned at my expression of dismay. “We’ll do another one,” he said by way of comfort. “We’ll make many, many more.”

At night, Tagong is a bit rough, the guesthouse grandmother had warned. As I lay in bed and listened to the sounds of the night outside, muffled shouts and the endless barking of dogs, I thought: “Disco monks or no disco monks it’s time to leave.”

I needed to get further off the beaten track. South of Tagong and toward the Yi minority region is an area known as Minyak (木雅 Mùyǎ), home to Sichuan’s tallest peak, MinyaKonka (贡嘎山 Mountain Gongga). Since the mountain has claimed the lives of several climbers in recent years and I had only packed Victoria’s Secret flip flops and a pair of trendy boots, I wasn’t planning to do any mountaineering. Indeed, I was looking to mount something else entirely.

Though the Minyak are classified as Tibetan, they have their own distinct language and traditionally keep their distance from the warrior-like Khampas. In fact, despite claims in the history books that the Minyak kings presided over a period of great scholarship, they were frequently bullied by Khampa men, and thus, it is theorized, built stone towers to guard against attacks. Many of these towers still stand today, like slivers of medieval castles pointing crookedly into the sky. I only glimpsed flashes of them from my bus window, but it’s easy to find a guide to take you around a few in Shade Town (沙德镇 Shā dé zhèn) (a two-hour drive south of the Zheduo Pass).

Reading up on the Minyak men, I was somewhat less than impressed, but was honor-bound to press on as I’d been invited to visit by a friend who works there restoring old buildings.

When we reached Wayao Village (瓦摇村 Wǎyáo Cūn) it was deathly silent, the quiet punctured only by the grunting of disconsolate sows that lay like great quivering sacks all over the village. An old lady appeared and picked her way delicately across a puddle. “Everyone’s gone off to the picnic,” she explained. We walked around the village, delighting in the quiet and the sense of history that emanated from the ancient homes, which, like the towers, had a medieval feel. The houses stood several stories high, made from closely packed stone topped with wooden beams and small dark slits for windows. The tiny temple in the center of the village had been boarded up as everyone was away for the picnic, so we walked the four or so kilometers through the beautiful wooded countryside to the picnic site.

Tibetans love picnics almost as much as life itself and they can last for days. People had put up gaily decorated white and blue tents filled with food and drink along with some sleeping couches. Outside, a riot of prayer flags billowed in the breeze, presiding over dancing, music, singing, as well as running and wrestling competitions.

We arrived just as a race was ending. In the middle of a field, a giant teepee had been erected from strings of prayer flags, and everyone was sitting in a circle around its circumference. I was given a rolled up carpet to squat on and a can of Red Bull. A young boy in a purple shirt sidled up and sat next to me on my carpet. He was barely out of his teens so I tried to maintain the aspect of a disinterested teacher. One by one members of the audience took the microphone and burst into song, triggering short spates of applause. Next, lines of dancing women got the men whistling, Mr. Purple Shirt included. Someone passed us a handful of sunflower seeds. But the Minyak looked smaller and shyer than my legendary Khampas and I told my companion we needed to head deeper into Kham country.

The next day we set off on a two-day trip of bus torture to Seda (色达) in the north of Ganzi County (甘孜县 Gānzī Xiàn). The journey was only made bearable by the breathtaking alpine scenery and the sight of brooding nomad men in their long cloaks leading herds of dancing yak.

Seda is like the end of the world. The small outpost perches more than 4,000 meters above sea level and is famous for its Buddhist Institute a few kilometers outside of town. More than 10,000 monks and nuns study here, and their homes cling to the hillsides in their thousands. The day we explored this warren of maroon-clad humanity, it had rained, and the roads were caked in mud. A freak hailstorm, which turned the sky an angry purple, drenched us in seconds. If the end of the world is really set for 2012, as some dubiously interpreted prophecies would have us believe, it just might start in Seda.

In town, I was struck by the handsomeness of the menfolk. They winked and smiled but never lingered long enough to exchange phone numbers. Many were dressed in wool-lined coats and wore jaunty red scarves in their hair. Perhaps they could be caught at night? We trawled the town for night spots. The local disco was empty but another bar was packed and required a minimum charge of RMB200 per person. The live show was a troupe of Chinese performers, all under four feet tall, who sang and told raucous jokes. We fled. The whole town was buzzing with the news of these vertically challenged visitors from Hubei Province. The next morning at a Tibetan breakfast café, a Living Buddha monk arrived and sat down for a chat. “Guess where I was last night?” he asked gleefully. Yes, he had been to see the show. We told him the performers were from Hubei. “Is everyone from Hubei that tiny?” he asked innocently.

I had told the attendant in my hotel—a cheeky young girl who loved asking personal questions—to introduce me to some handsome Khampa if any checked in. So the next night, my door burst open to reveal a doe-eyed nomad boy, all of 17 years old, standing in the doorway. The desk girl gave him a little push and he stumbled in, awkwardly inviting me to his room to watch a video. Curious, I agreed. The video turned out to be a pirate copy of some trashy Hong Kong series. He seemed awfully shy and unsure of his next move, barely managing to make small-talk. “Are you excited?” he asked. “No,” I replied and legged it back to the safety of my room.

The next day my friend and I retired to our favorite Tibetan teahouse. The potato momo (馍馍, a type of dumpling native to Tibet) were exquisite and we knocked back cup after cup of the Lhasa milk tea. It also happened to be a good vantage point for watching the local men. The owner, a smart woman in her late 30s, and now a good friend, came over and joined us. I told her of my quest.

“You don’t want a husband like mine,” she said sternly. “He’s good for nothing, lazy and sexist. He expects me to do everything. When we’re at the dinner table he doesn’t even look at me, just taps his cup and grunts to tell me he wants me to refill it.”

“Do you still love him?” I asked.

She thought for a while, playing with her yoghurt spoon.

“Yes, yes I do,” she smiled.

After the incident in my hotel room, my resolve had been flagging, but these words were all the encouragement I needed.

I winked at the customer seated at the next table and, to my delight, he winked back.

Like the article? You can buy the rest of our Social Media Issue in our store.