Debut experimental fiction about a Chinese factory strike evokes universal themes

Experimental: A word which inspires both promise and disquiet.

I once dated a woman who described our relationship as “experimental.” Unfortunately, our relationship didn’t last long enough for me to find out the results.

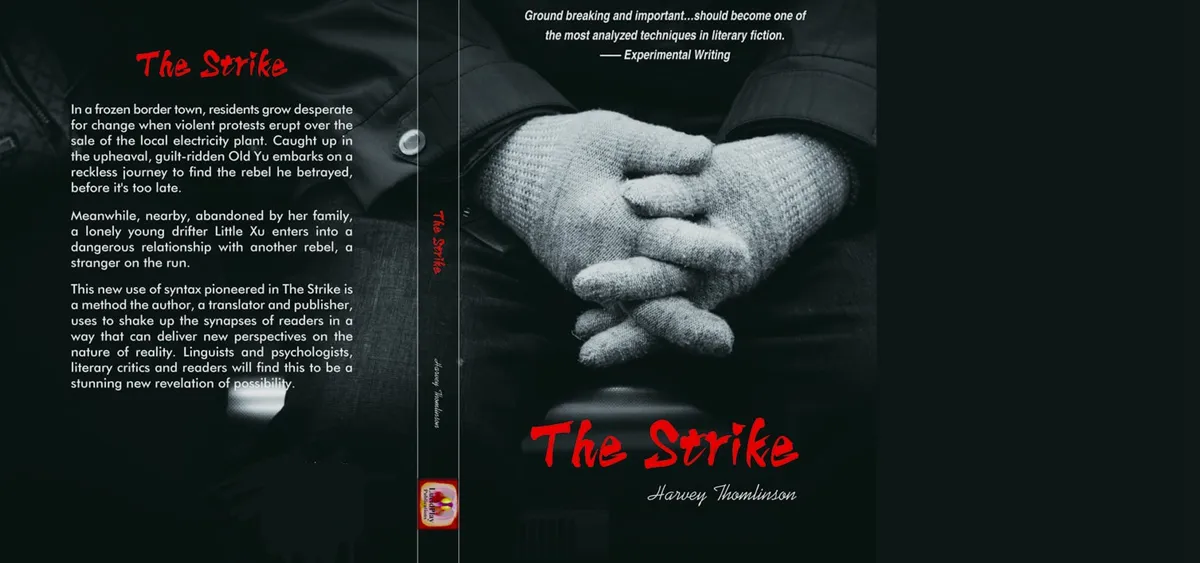

Translator and writer Harvey Thomlinson describes his new novel, The Strike, about “an illegal protest in a frozen border town,” as experimental fiction which “uses a linguistic strategy which aims to subvert expectations about the correspondence between syntactic and semantic structures.”

What happens when the form of writing is insufficient to express the multi-dimensional world of thought, time, and perception which we inherit? Why, asks this book, should we be limited by tense to understanding a story purely in one temporal space when our lives are lived as a farrago of memories, present perceptions, and future hopes, and fears?

She was Xu Yue lay on her side to stay asleep the sheets had crawled up her thighs a day yet to penetrate. When her eyes opened she couldn’t breathe sometimes they turned up the heating so high she saw chairs with spaces inbetween.

Across the morning her legs stretched remotely sensations stirred last night’s clothes piled on the bed. Because it was Saturday there was no hurry to move a dirty plate on the floor unless she wanted to. She stayed there lazily enjoying the soft pillow in her mind dusty light sparkled like emotions.

She looked out across the misty sea of winter-weathered apartment blocks half a galaxy from her village she lit a first cigarette.

Thomlinson’s use of experimental language can be challenging, not unlike listening to the music of Ornette Coleman or an evening of Schoenberg. It took me some pages to begin to feel the melody in the rhythms and to begin to hear a new palette for the construction of tense and syntax.

Even the cover blurb features ‘Experimental Writing’

It is not only the language which challenges the reader. The story—loosely based on a real events Thomlinson witnessed during a trip to the far northern regions of China a decade ago—moves at varying speed, depending on the mood of the characters. Dramatis personae appear suddenly, only to disappear for chapters at a time. Bit players evolve into important protagonists. Key characters evaporate. It is messy, confusing, unconstrained by thinking in specific times, acting in specific spaces, or any form of omniscient narrative momentum—not unlike the way real people live their lives.

When writing fiction in a cultural context different from that of the author, there is always the danger of (mis)representation and cultural appropriation. Perhaps more so in a book which goes to great—often uncomfortable—lengths to interweave the internal voice of its characters and the mentalité of a community into a larger narrative.

And yet perhaps in the universalism of themes (regret, lost love, excitement, self-interest, hurt, joy, fear) there is also something which transcends the setting. These characters exist in a cold, snowy part of forgotten China. They are utterly banal but live in extraordinary circumstances. Perhaps this is what allows the story to transcend the particularity of culture and nationality—and place them in the universality we all share.