How a low-budget comedy about sexist boyfriends became a box-office smash

It’s sometimes easy to forget how distortive mainstream situation comedy can be: Few 50s families ever did Leave it to Beaver, rare are the real-life Friends who could afford Manhattan brownstones in the 90s, and most bars in Boston don’t know your name. Yet the influence of such shows can be pervasive: A cosmopolitan Friends fan once bitterly complained that none of her girlfriends were Phoebe and it was “impossible to meet a Chinese Chandler.” The disparity between life and fiction seemed to be genuinely frustrating.

In China, it’s typical to hear that the post-90s generation is wiser, less materialistic, more hip to the squareness of elders yet indifferent to their conventional demands. The success of the final installment in the previously little-known The Ex-File series belies much of this thinking—even if its merit is simply material (a 237 million USD opening weekend) and its significance is probably as transient as most mainland zeitgeists. For now, though, the low-budget smash The Ex-File 3: The Return of the Exes (《前任3:再见前任》) is a cultural phenomenon, having trounced Disney’s heavily armed Hollywood rival The Last Jedi at the January box office, and nearly tripling the latter’s opening for a fraction of its marketing budget, despite a brutally average rating on Chinese film review site Douban.

Most of the Huayi Brothers’ production’s receipts come from the generally neglected, disdained, yet vast audience of the “middle class masses”—young strivers living in third-tier cities with little leisure opportunities and high social ambition, who view cultural centers like Shanghai and Beijing as the apogee of success and sophistication (McKinsey calculates that 55 percent of these households in this class earned an annual 60,000 to 100,000 RMB in 2012, and, by 2022, eight percent will have upgraded themselves to “upper middle class” status).

In plot and tone, The Ex-File imitates more mainstream series like If You Are The One or the benighted and “ridiculous” Tiny Times trilogy (better translated as “Times of Gold Filligree”). The wealthy white-collar characters of these franchises enjoy a lifestyle far beyond the average Beijing homeowner, who is normally to be found trying to meet mortgage payments while juggling overbearing parental and societal demands.

By transplanting the standard rom-com formula—white middle-class anxieties, reimagined in Chinese metropolises—mainland comedies can often seem spectacularly out of touch, even by Hollywood standards. They typically showcase a lifestyle in which the protagonist frets about work, but rarely attends, and other characters are oddly focused on the plotlines of the courting couple, rather than, say, their own quotidian troubles. In real life, most Chinese middle-class complain about the overwhelming demands of modern-day corporatism, and rarely have time for a social life. As such, these films are expected to provoke aspiration as much as amusement.

In The Hangover, which is as typical a template of the modern male “buddy comedy” as any, the Vegas-based screenplay allows for a scenario that’s both credible and comedic—three men on the tail end of a boy’s weekend, trying to piece together the previous night—even as the decidedly deadbeat characters are pummeled by its plot. The script is certainly sexist, but the punchlines are usually at the heroes’ expense.

The Ex-File 3, by contrast, seems to have been sponsored by Vogue China and its central characters are straight-up Weinsteinian in attitude. Chinese viewers on Douban have called it a “typical patriarchal brainwash” that can never be shown on big screens overseas, while another says the moral of the story is that “as long as you are a woman, there will always be a good guy to accept you, and take care of you for your whole life.”

Male leads, meanwhile, are slammed for their ridiculous garb and costume changes one could expect at a couture show: floral-print shirts with check trousers, red suspenders under a single-breasted plaid blazer, and, at one point, a leather yellow safari suit. A heavily lipsticked Meng Yun (Han Geng) casually sports a black suede waistcoat over a houndstooth shirt as he bonds and banters with Yu Fei (Zheng Kai) over drinks, as we learn that “girls only have a few good ‘golden years’” and “a man who doesn’t spend money [on a woman] must not love her”.

To serve the weak plot, these central characters hop between various locations like visas and travel permits don’t exist—whale watching in Rio and lapdancing in Macau as the film’s erratic mood serves. Interestingly, there are three female leads and only two males—no points for guessing the story arc—not including a brief scene in which the boys confidently try to bed twins, only to discover the pair are not actually identical; this is then an opportunity for the “brothers ignorant” to flaunt their hopeless knowledge of genetics. There are gay jokes and trans gags. One plot thread climaxes with a man bellowing, “I love you” in a town square, as his love interest gnaws thoughtfully on a peach and considers her options (one might have warned her not to marry anyone who thinks women are “used up” before they’re 30).

Who’s sponsoring this? Disappointingly, for those hoping that the #MeToo movement to take root in China, the film’s main target audience largely overlaps with its chief victims: Surveys shows that under-24 females, from outside first-tier cities and regions, and lacking higher education, are those flocking to see the film.

Clearly, this is a film for the ages—that is, 18 to 24, and not the type of youngsters you see in books like Guo Jingming’s Tiny Times (or indeed the Ex-File). According to the stats, they are are provincial and positive-minded, generally apolitical, but far less prepared than their parents for the economic meat grinder that probably awaits them. It’s natural that this audience will empathize with a domestic film about overcoming emotional adversity more than, say, the eighth installment in a long-running Western space opera—even if its outlook is overwhelmingly masculine, while The Last Jedi has a number of positive female role models in leadership roles. Few Chinese may be nostalgic for lightsabers, but everyone has an ex.

Two More Must-See Movies

With the cheerful irony of its title—and a fantastic mood soundtrack by the Shanghai Restoration Project’s David Liang—Liu Jian’s Have A Nice Day announces its noir intentions even before its gangster villain, Uncle Liu (Yang Shiming), utters the first lines of dialogue: a series of Tarantino-esque childhood recollections made while torturing an old friend.

Over the next 77 minutes, the film follows a man-purse full of a million RMB (about 125,000 USD) as it is repeatedly stolen, first from Uncle Liu, then Xiao Zhang (Zhu Changlong), a bagman with hapless ambitions to buy his fiancée a round of cosmetic surgery in South Korea (after a botched operation somewhere in China). Of course, this being noir, the fiancée intends to steal the money for herself, along with her cleaver-wielding lover. Getting in the way of this love triangle are a number of lowlife characters, including Skinny (Ma Xiaofeng), an ice-cool assassin, and an internet café owner (Cao Kou). The latter is a dab maker of outlandish gadgets, including a pair of functional X-ray specs and a single-shot gun stick, the revelation of which caused cinema-goers in Beijing to whoop with delight.

Not since Cai Shangjun’s 2011 underworld classic People Mountain, People Sea, perhaps, has a mainland movie presented such a grimy and uncompromising look at the criminal demimonde. Its ligne claire look recalls the TV series Archer via Waltz with Bashir. The plot is animated in a minimalist style, with flat palettes that detail every flake of peeling paint, scrawled graffiti, and illicit posters adorning the streets and buildings of this unnamed southern city. Fortunately, Have A Nice Day demonstrates a jet-black humor and cultural savvy that singles it out from other domestic output—references to Deadpool, The Godfather, and The Fast and the Furious, among other movies, and a soundbite from Donald Trump; there’s even a joke about Brexit, a rare sense of contemporary realism found in a domestic film.

In between beatings and the occasional bullet, the hard-bitten anti-heroes find time to muse on education, the future, even freedom—defined here entirely in terms of consumer choice—in guttural growls. Yet everyone is evidently trapped in an endless cycle of squalor, epitomized by the locations and tropes that keep recurring in the relentless pursuit of the money (the new Chinese title, Dashijie, translates to “The Big World,” referring to the usually seedy entertainment venues found in anonymous provincial cities).

It’s an unusual level of social criticism rewarded on the international festival circuit with a triumphant debut at the Berlin International Film Festival, although a later showing at Annecy was sadly canceled in an unnecessary controversy over exit visas. It’s a relief, therefore, to see the film playing to appreciative audiences in China six months later, suggesting that Have A Nice Day is destined to be regarded as a animation classic, both here and abroad. - H.R.

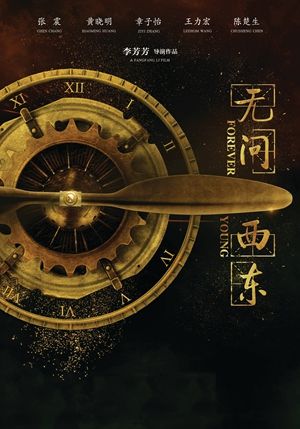

In 1923, a college student is stuck between the choice of science or humanities in an era when the former was expected to save the country; in 1938, a promising young scion of an affluent Cantonese family abandoned his studies to become a fighter pilot in the war; in 1962, three former high school classmates are trapped in a love triangle then caught in a storm of collective insanity; today, a young professional struggles to balance altruism and an office culture that prioritizes profit. What they all have in common are a Tsinghua University degree and the strength to follow their hearts in adversity, with each generation leaving legacies for the next. Shot in 2012 for the centennial of Tsinghua University, with a star-studded cast including Zhang Ziyi and Leehom Wang, Forever Young surpassed its original commemorative purpose, as proved by its box-office record of over 700 million RMB since its commercial release in January. Viewers, though, are very much divided on a film that critics have deemed excessively sentimental. There’s also no official explanation for its long-delayed release. – Liu Jue

The ‘Ex’ Factor is a story from our issue, “The Noughty Nineties.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.