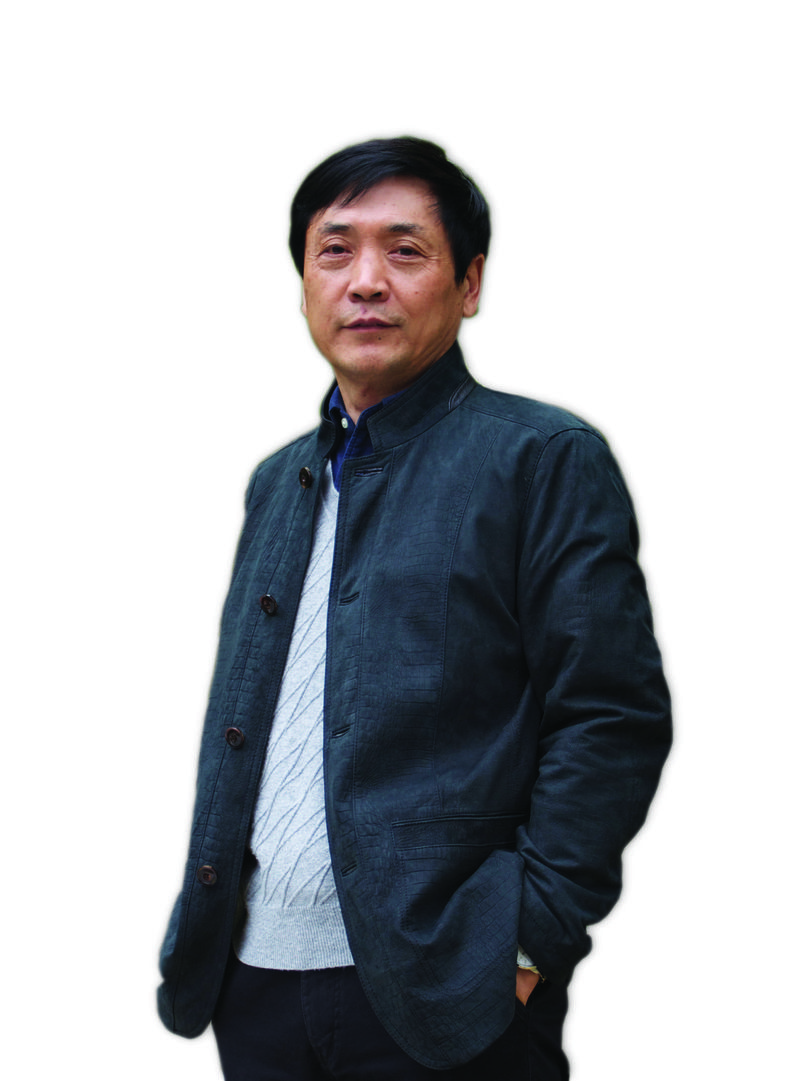

An interview with Cao Wenxuan, the first Chinese author to win the Hans Christian Andersen Award for children’s literature

Cao Wenxuan is the winner of the 2016 Hans Christian Andersen Award, the highest international prize for children’s literature, along with German illustrator Rotraut Susanne Berner. Cao, a 63-year-old Peking University literary professor, is a household name in children’s books, winning most of the top prizes available in this genre and having published more than 20 novels since the 1980s.

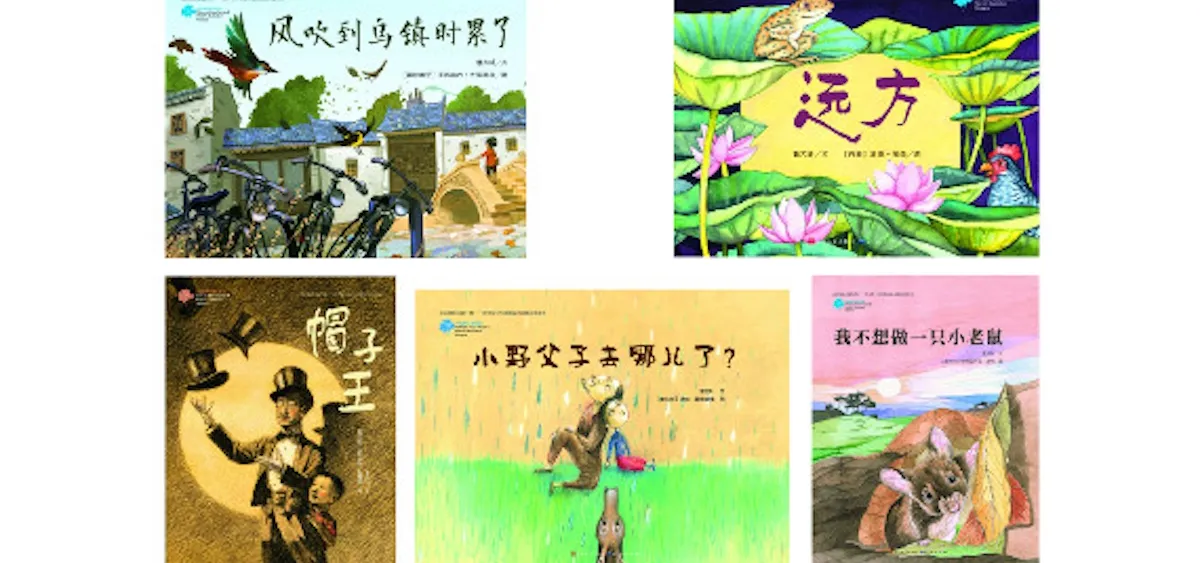

His renowned novel The Straw House, published in 1997, is required reading for secondary school students, while his 2015 novel, Fire Mark , sold 100,000 copies in a single month. Cao’s novels have also been translated into over 50 languages and Bronze and Sunflower is one of the most popular overseas. Cao grew up in rural northern Jiangsu Province, with the hardship of his early years forming the inspiration for much of his work.

Cao’s stories are noted for their realism, often tinted with sorrow and themes of coming-of-age, coping with loss, and the impact of war on children. Patricia Aldana, jury president of the International Board on Books for Young People explained their decision for the award: “The unanimous choice of the jury, Cao writes beautifully about the complex lives of children facing great challenges.”

What does it mean to you personally to be the first Chinese writer to win the Hans Christian Andersen award? What do you think its impact will be on the larger Chinese literary scene?

I wasn’t particularly excited when I learned about it. To me personally, my win confirmed an assessment I made years ago. I made the claim that the best Chinese children’s literature is up to the highest international standard, but no one believed me back then. With this award, many will recognize and agree with my assessment. For many years, Chinese literature has been underrated and undervalued by our own critics, so I’ve stated on a number of occasions that we owe our thanks to Mo Yan. With him winning the Nobel Prize for literature, the voices questioning the quality of Chinese literature dimmed. I believe that with increased communication with the world, there will be more Chinese authors winning international awards, that Chinese literary voices and their influence will become stronger.

It seems that bronze and sunflower is the most popular novel of yours for foreign audiences so far. Much of this depicts the cultural revolution and the heartwarming relationship between two children during this time. Could you tell us a little bit about your inspiration for this story?

More than a decade ago, a friend told me of her childhood experiences: her father took up labor in a school for cadres. She went to visit him. There was nothing to do in the school, so she went to play with the village kids on the other side of the river. I knew a great deal about schools for cadres since my hometown also held one. So, a story began to appear in my head, it was more like a picture: a city girl came all the way from a far away metropolis to a simple village. She made an acquaintance with this farm boy. Then another day, the phrase “Bronze and Sunflower” suddenly came to me and it hit me that the story had matured and now had a “soul”.

The boy would be “Bronze” and the girl would be “Sunflower”. City girl Sunflower came to the village and became close friends with the village boy Bronze. Then a vast sunflower field spread before my eyes and the girl’s father appeared. He’s an artist, a sculptor; all his life he has been making sunflowers with bronze. The rest of the story just flowed naturally.

By comparison, your recent series legends of the dawang tome is more of a teen adventure fantasy that takes on a darker tone, quite a shift from your past work. Why the change?

Legends of the Dawang Tome is a fantasy series I spent a lot of effort on. At the time, Harry Potter and other fantasy fiction stories from abroad were very popular in China. Fantasy also became a hot genre for local writers. But most of their works were wild imaginings involving magic and other common fantasy elements in the West; in essence, they were all imitations of Harry Potter and other Western works. What they lacked was not imagination, but the life experience and knowledge to support it.

So, they ended up with hollow imagination and poor quality. When I was writing the Legends of the Dawang Tome, my goal was for it to be literary first, then fantasy. A good fantasy work does not just require imagination but also a great plot, intriguing characters, food for thought, and reflections on humanism. Legends of the Dawang Tome is a fable of human intelligence and their ultimate fate. I long to create a narrative that’s grand in scale and depicts spectacular scenes. War and Peace, along with Quiet Flows the Don are some of my references. I carefully read and contemplated scenes of war, cruelty, and bloodshed, hoping to benefit my own writing.

Some foreign reviewers mention the question of a recommended age range; at times, there are graphic descriptions of violence and suffering, as well as sophisticated vocabulary, which are probably suited for older children. This has also been mentioned as a common problem for bringing chinese children’s literature to the west. What’s your assessment of this opinion?

Chinese vocabulary-wise, my work is suitable for children above the third grade, but one third of my readers are actually adults. I’ve always thought of myself as an atypical children’s literature writer. I do not write entirely to cater to readers. I view children as equals instead of looking down them in terms of writing. Writing from a child’s point of view to reveal some of the common problems faced by all people and all the world through their stories is my focus. Top children’s literature, such as The Little Prince and Charlotte’s Web, is suitable for all ages, and I want my work to be that way.

“The Power of Pain and Sorrow” is a story from our newest issue, “Romance”. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.