Zhang’s marred childhood led to some very provocative art work

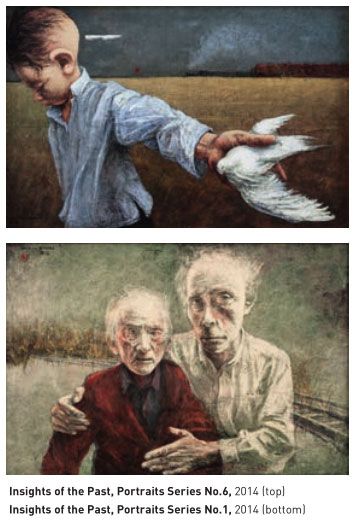

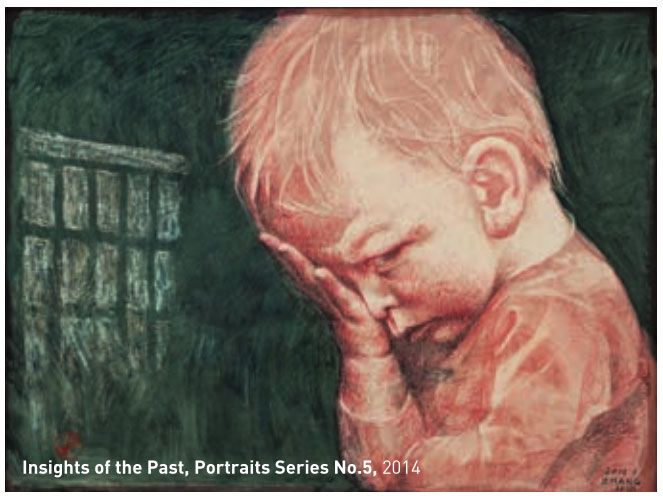

Zhang Linhai’s (张林海) studio is located in Songzhuang, an oft-overlooked art zone located in a village northeast of the Sixth Ring road. His spacious studio is covered in portraits of children—a school boy sitting under a Communist leader’s portrait with his head hung on his chest, drained of all vitality; another depicts a boy playing a lost and woeful version of hide-and-seek. A half-completed painting features a boy aiming at the viewer with a slingshot, his face twisted in a queer jest. “It has a kind of cruelty that does not fit a kid,” Zhang says, smiling sadly. Unlike the hollow, listless, over-duplicated faces that plague the likes of 798, the loneliness, despair, and dejection in Zhang’s portraits are powerfully evocative.

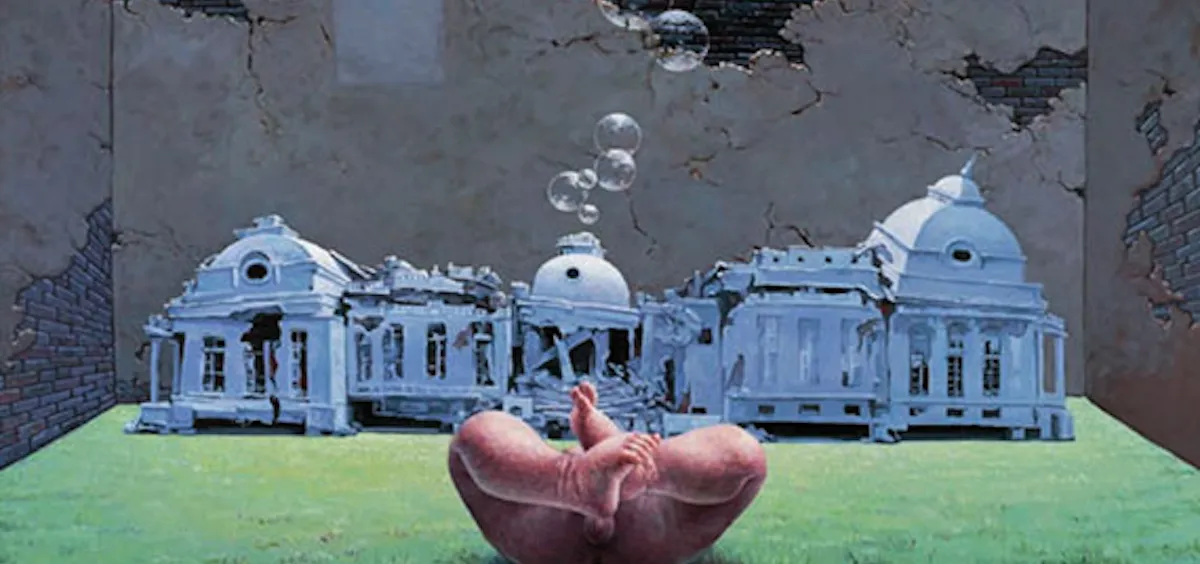

Some look at Zhang’s work and see the artist’s own childhood trauma, but speaking of this, Zhang chuckles in embarrassment. He has been asked this question many times before, and he always confesses that he did have a somewhat marred childhood. He was an adopted child, having gone through a disease that still affects him today, and during the Cultural Revolution he watched his father’s public torture. To some extent, that era still haunts Zhang’s works—the ideas and symbols of collectivism, zealous ideology, and Soviet-style architecture all feature heavily. Zhang describes it as “all sorts of ridiculous things that only my generation understands.”

This isn’t to say Zhang’s works are dated, far from it. Indeed, it’s hard to say what has made Zhang what he is now: his own past or the Chinese children today experiencing a childhood that is no less traumatizing. Despite being several generations apart, Zhang has a knack for accurately capturing the zeitgeist of Chinese children today, an issue that concerns him greatly.

“I’m intuitively more sensitive to the situation of the lower classes and the underprivileged,” Zhang says. “Perhaps that’s why my subject is always children. The children I paint are never happy. Can you truly say Chinese children—urban or rural—are spontaneous and happy?” Zhang says. “In rural China the children are suffering from a childhood with absent parents, which is worse than poverty. The children in cities are nowhere better; they are much better off materialistically, of course; but their mentality is twisted by other things, such as so-called ‘education’. Some may ask, is this what the present generation of Chinese children are like? Think it over twice, and you will realize that, yes, this is what they really are like.”

“Art is always the mirror of our times,” Zhang says. “I’m lucky that I still retain the passion for painting this subject. I may not be able to change anything, but as an artist, I can at least present a depiction of our times.”

“Gallery” Childhood Trauma” is a story from our newest issue, “Military”. To read the whole piece, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.