A field nurse remembers a harsh winter in the wake of a war with aliens, when his father died at their hands

Former editor of ‘Science Fiction World’, a base for modern Chinese sci-fi literature, Chi Hui is one of the leading figures of a new generation of sci-fi writers. Many of her earlier works focus on the impact technology has on the spiritual world of people and their environment. Her novel “Kalemi’an Graveyard” (《卡勒米安墓场》) in 2010 centered on a young woman, the daughter of a space pirate captain, and her quest to find a mysterious graveyard only mentioned in legend.

I remember that winter. Thick snow weighed on the window’s eave and hung down, stuck on the edge like a quilt roll. My uncle kicked out the door. Shouting family members lifted my dad onto the plank and rushed him to the hospital. I squatted in the doorway, tapping his frozen boots. His toes dropped out one at a time, and I cradled them in the padded breast of my jacket. I thought they could be reattached. I thought doctors had superpowers.

Once I grew up, I learned that doctors did have powers, and that it took a lot of money to become one. My widowed mother didn’t have that kind of cash, so I signed up for nursing school. My teachers liked me. Male orderlies were rare and I was a guy, with muscle.

Do you have any idea how hard it is to roll a 90-kilo patient covered in bedsores? Flesh pours over your hands, like a liquid. You can’t find a place to grab the skin. Two orderlies need to half squat in a fighter’s horse stance. You both lift from beneath, brace, one, two, three, and flip the patient over.

Later, we were drafted to a field hospital. That was easier. The guys that lay on those beds were scrawny. Sometimes fatter ones were brought into special care, but we weren’t on that duty. The floor at our entrance was covered with guts, blood, and amputated limbs. We would roll patients out of the odors of the makeshift ER, and in less than a few days we probably rolled them into the stench of the morgue.

I met a nurse. She wasn’t that beautiful, but she laughed with white teeth. Her voice was also pretty. We agreed to get married after the war, but not even a month passed and she was transferred to Wangsa. The city was H-bombed three days later.

The war ended, but it was just another assignment. A few orderlies and I were transferred to the south. It got hotter as we travelled, then cooler. We rode on trains, then boarded an airplane and flew until we reached the South Pole. The sky was a terrifying blue and the ground wasn’t white, it was black. It had been bombed. They issued heavy clothing, saying we had to wear it or we would die. There was radiation, that much I knew.

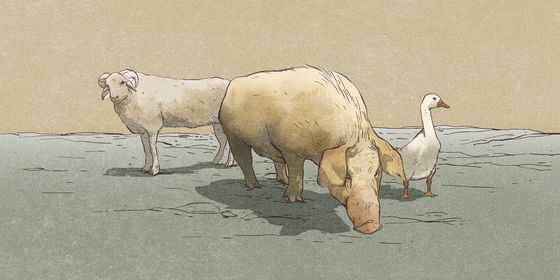

The field hospital was erected rapidly. Even though the fighting was clearly over, it was still built in that rushed army way. The people brought in, however, they were uncanny. Six digits, two heads, four legs and one arm. And the arm grew out of their butts. I knew they were aliens, the kind we were fighting. They were frozen solid. Just like my dad when he died.

The doctors were experts. They put together a lot of complicated machines and tubes, saying they could, “defrost these fellas”.

I hated those “fellas”. Thoroughly. They started the war. They dropped the bomb that killed my future wife. But I did my job. If the doctors asked for something, they got it.

There were six aliens in total, and each of them was put in a thawing chamber. The doctors paced the temperatures. They looked nervous and worked cautiously.

A red light started flashing. It was blinding. Alarms went off. The blue observation cells exploded, discharging foul water. It was rancid.

The aliens were all dead. I helped the doctors tidy up and scrub the floor with a brush. We soaked up the rancid water with rags that were wrung out into beakers. The doctors said they would continue their research.

Let them have at it.

I returned to the mainland, resigned from my post, and found a job at a county hospital. I married a widow. She has a sound boy that calls me dad.

Sometimes I dream about that night when I was a child. My dad dug life forms, with four legs and two heads, out of the snow. They were frozen solid. He was hoping to sell them, but it was an unusually cold night, deathly freezing, the coldest out of all the winters I can remember.

The organisms came to life. They touched my dad. He fell. His head cracked open and his toes stayed in his boots. He was frozen solid.

There might be a kind of organism that comes to life in the cold and hardens in heat. But I didn’t tell those doctors.

I will always remember that day. I remember crying as I raced over the snow. The strange life forms had left and I thought the hospital could save my dad. His toes were melting in the breast of my jacket. Bloody water soaked through the cotton pads. It leaked into my undershirt and down my chest.

Translated by Nicolas Richards (芮尼克).