Deception and ingenuity in the weird world of bogus antiques in China

Panjiayuan is China’s biggest antique trading area, located south of Guomao in Beijing, and is without doubt the country’s CBD of antiques. On the area’s southern outskirt is China’s biggest fake antique wholesale market, Shilihe Antique Plaza, where every morning mud-stained Buddha statues and green-rusted bronzeware are shipped from places like Shanxi and Henan, professionally packed, and sent on their journey to destinations all over the world. With China’s new demand for increasingly expensive antiques, it’s no surprise that the fakes are often difficult to tell apart from the real thing, something one young man in Panjiayuan knows all-too well.

“It’s impossible to buy genuine old stuff in Panjiayuan now. Maybe 10 years ago you could, but not now,” says a short, young man with sincere eyes and a loud Southern accent. Having just arrived directly off the train from his home village in Jiangxi Province to his old customer’s apartment, he put his old worn backpack on the ground and took out, one by one, goods wrapped in layers of toilet paper: six plates and bowls from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) emerged and were laid out on the ground. The man is a grave robber and antique smuggler. When I told him that I had assumed grave robbers were archeologists or at least those with a cursory knowledge of history, both he and his buyer looked at me in surprise: “Nonsense!” he exclaimed. “All of them are peasants.”

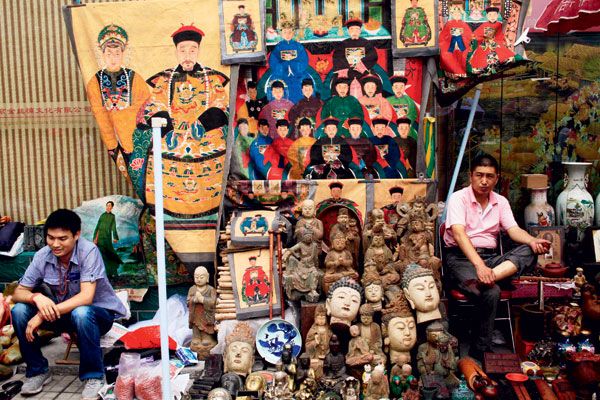

Two merchants sell their dubious wares in the famous Panjiayuan antique market in Beijing

Quite talkative and seemingly unaware that his profession is of interest to many—as well as being exceptionally candid for someone whose job is extremely dangerous, illegal, and pretty immoral—he went on to enlighten me: “It’s very simple. We look for a circular hill slope facing north, that is the best feng shui, where the rich and noble were buried. And, then you get the middle class in slightly worse feng shui spots. But in recent years there are so few graves left, we are reduced to stealing from very common people; they barely have any possessions.” These modern times aren’t suited to sales either: “We have not sold in Panjiayuan for a long time; we usually sell the goods directly to old customers.”

Hardly a novice, he has been an “antique dealer” for over a decade, and Panjiayuan is where he started his career. He knows that so-called experts in antiques can be wrong and cost him cash. “Over 10 years ago, an antique expert from the Forbidden Palace Museum visited my stall with a buyer. She identified the things I dug out of graves myself as fake, but bought a plum blossom vase this tall (his hand leveling his chin). Even I could tell it was new at a glance, and she insisted that it was old.” Authenticity matters little in China’s bleak world of antique fakes.

Indeed, the antique business in China is never short of scandals, and most scandals come from established antique experts who work in state-run institutions. In 1994, a couple of Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) terracotta figurines turned up in the Panjiayuan Antique Market, very rare items and highly sought after. The China History Museum (now China National Museum) and the Forbidden Palace Museum carefully studied them, and they passed both human and modern technological examinations. The experts applied for funds and rushed to buy them all. Antique collectors, of course, followed suit and arduously fought for these figurines. However, as more and more o f these “rare” figurines kept showing up at the market, experts soon realized that something was wrong. The National Historical Relic Bureau started an investigation into the matter, and it turned out that they were all the product of a single village in Henan, all made by peasants who earned a bamboo basket for each figurine sold.

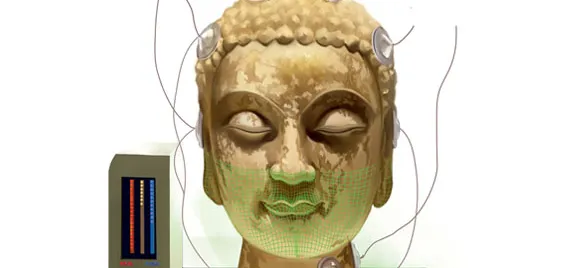

A Yanjian villager local in Henan Province working on a clay bronzeware mold to make realistic faux antiques

In 2007, Shi Shuqing (史树青), the vice director of the National Antique Identification Committee and senior research fellow o f the Forbidden Palace Museum, who passed away that year, bought six Warring States Period (475BCE-221 BCE) swords at a price of 1,500-1,800 RMB each. He believed them to be authentic and wanted to donate them to the Forbidden Palace Museum, but these bogus swords turned out to be fakes, and the donation was rejected. Later, antique dealers pointed out that the swords were easy to spot as counterfeits, but Shi insisted on their authenticity until his death.

Perhaps most impressively, the sensational scandal of the “Han Dynasty” (206 BCE-220 CE) dresser and matching stool, both wholly carved out of jade, appearing at auction in 2011 ended up being the most expensive jade antique in the world. The identifying expert was Zhou Nanquan (周南泉), reputedly the number one jade authority in China and a Forbidden Palace Museum research fellow. The final price tag was 220 million RMB. A year later, its makers, a jeweler and several young craftsmen in Jiangsu Province, discovered the sale and spoke up. They spent a year making it and sold it originally, as a work of art, for 2.3 million RMB. They claimed to have no idea how it came to be dated as “Han Dynasty”, especially considering that, in the Han Dynasty, people sat on the floor and no stools from that period have ever been discovered. Also, jade at that time was only used as jewelry for noblemen. Nevertheless, disavowing history, Zhou Nanquan sticks to his judgment to this day.

Scandals like this have made headlines such as “Forbidden Palace Experts No Rivals for Henan Peasants” far too frequent. Sometimes, for an experienced collector, a piece having been identified by governmental antique experts can be a poisoned chalice. Why is this rivalry so unevenly matched?

“In the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) and in the People’s Republic Period (1912-1949), we had really good antique experts,” explains Li Yanjun (李彦君), founder of the Traditional Culture Institute of Beijing Oriental University, the only Chinese university with majors in antique identification and repairs. “But, things changed after 1949. China became socialist. All antiques and historic relics were ‘national treasures’ and not allowed to be privately owned, and people were not allowed to study them either.”

Between 1949 and the Reform and Opening Up in 1978, the antique market only sustained a phantom existence in the aptly-named “state-owned antique stores”, which sold exclusively to foreigners. Privately dealing in antiques was against the law and carried heavy penalties. With the market almost entirely non-existent, there was nowhere to foster a new generation of experts. The old experts in antique identification and repairs passed away without having the chance to teach their knowledge to others. Only after 1978 did the antique market once again come alive; but the gap had already been established, and the efforts were too little and too late.

“The best classroom for antique experts is the market, but now the most acclaimed antique experts all work in museums and research institutes. They do research on paper, but they are out of touch with the market; therefore, they are academically superior but always make a fool of themselves in real life,” says Li. “The real experts in China are antique dealers and collectors because of just one thing: they have spent loads and loads of money to buy their expertise. It’s like those who teach swimming in a classroom—they can never swim as well as a fisherman who spends his life on the sea.”

Nanshishan Village’s craftsmen take great care in making their fake antiques as real as possible

And in China, the “sea” is unpredictable and full of peril. Despite China’s famous ineptitude in certain creative industries, China has the most advanced techniques in fabricating counterfeit antiques. “I still regularly go to Panjiayuan, just to look at what’s new in the counterfeit industry,” Li says. “New methods are forever coming out, and I constantly need to learn.”

Except for a brief period in the 1980s, when antique forging was still in its infancy, Chinese identification experts have always needed to deal with the world’s most cunningforgers. In the classic case of the 1994 “Northern Wei” figurines, for example, to make sure the counterfeits were perfect, the peasants first got their clay material by grinding bricks from Northern Wei tombs, and the figurines safely passed the Carbon-14 dating test.

They are supreme artisans, too. Ni Fangliu (倪方六) is an expert in China’s history of fake antiques. According to him, different places in China have different strengths. “For example, Henan Province produces the best bronzeware. One of the most difficult steps in making bronzeware is to make the wax mold, but in Anyang, the village women have been making wax molds for many years and are all great masters.”

Sometimes, forgers in different places have to work in a combined effort. “Suzhou, Zhejiang Province, is known for faking ancient jade pieces because they can do the best carving. However, masterful as they are, Suzhou’s craftsmen have one problem: they can’t fake the particular luster and transparency that only ancient jade has, and this is usually the key factor that betrays the piece. They have to send the jade to Bengbu, Anhui Province, where the locals specialize in giving the jade its ancient luster. After their processing, few outsiders can spot the trick. It is a secret method only passed down from through family methods. Suzhou artisans tried to steal it, but never had any success,” said Ni.

Around the year 2000, modern techniques became widely applied in counterfeiting. “Today, people use computers programs to carve and imprint forged paintings and calligraphy. The technology is so advanced that they can look identical to the original piece,” Li Yanjun says. “Sometimes when a new antique scandal is broken in the news, a lot of people accuse the experts of being morally corrupt, that they were bribed to identify a fake as real. But I don’t think there is a moral issue involved here,” he adds. “Bribery may happen with not so famous identifiers, but not with these top-ranked experts. With their age, fame, and prestige, why on earth would they want such humiliation.? Logically, it doesn’t work. It’s only that they really couldn’t tell the difference between the real and the fake because they are too disconnected with the ever changing market.”

For high-end counterfeiters, Chinese museums are ideal potential clients. “It is estimated that five to 10 percent of China’s museum collections are counterfeits,” Ni Fangliu says. “But, I think the percentage is higher than that. Most Chinese museums, especially those in economically developed areas, have a special budget for purchasing antiques, ranging from millions to tens of millions according to the museums rank. In order to spend the money, the museums often hastily buy antiques that should have been more meticulously examined. Even if the museum is found out to have bought fakes, there is almost nothing to lose for the people who are responsible for it—they can still get their bonuses and the budget will stay the same.”

A three-color glazed figurine being painted by a craftsman in Nanshishan Village, Henan Province–from the “Tang Dynasty”

The major victims of counterfeit antiques are, of course, China’s average collectors. They can’t protect themselves against such professional counterfeiting, and Chinese auction companies are not responsible for the authenticity of their auctioned pieces. From 2006 to 2009, over 100 Emperor Qianlong (乾隆皇帝) seals were auctioned, but there are only three such verified seals on the market.

What’s worse, being new to antique collection, a lot of Chinese people look at it as an investment rather than a hobby. Such a mentality has led to some very irrational speculation. Shi Tai has been an antique dealer in China and the US for over 20 years. “Compared to Western collectors, in China there are relatively few collectors who collect just out of passion,” he says. “Right now, eaglewood and red agate are all the rage in the collection business, but they obviously aren’t worth their current price and the bubble will bust sooner or later.” Prior to that, the prices of Tibetan Dzi beads and ancient bronze mirrors saw dramatic ups and downs, selling as high as tens of millions before plummeting back to the normal price.

“China’s antique business is ridiculous,” Li Yanjun concludes. “But, you can’t help thinking, at least it’s interesting.”